Search Results

Iceland’s recovery: myths and reality (or sound basics, decent policies, luck and no miracle)

Icelandic authorities ignored warnings before October 2008 on the expanded banking system threatening financial stability but the shock of 90% of the financial system collapsing focused minds. Disciplined by an International Monetary Fund program, Iceland applied classic crisis measures such as write-down of debt and capital controls. But in times of shock economic measures are not enough: Special Prosecutor and a Special Investigative Committee helped to counteract widespread distrust. Perhaps most importantly, Iceland enjoys sound public institutions and entered the crisis with stellar public finances. Pure luck, i.e. low oil prices and a flow of spending-happy tourists, helped. Iceland is a small economy and all in all lessons for bigger countries may be limited except that even in a small economy recovery does not depend on a one-trick wonder.

“The medium-term prospects for the Icelandic economy remain enviable,” the International Monetary Fund, IMF, wrote in its 2007 Article IV Consultation

Concluding Statement, though pointing out there were however things to worry about: the banking system with its foreign operations looked ominous, having grown from one gross domestic product, GDP, in 2003 to ten fold the GDP by 2008. In early October 2008 the enviable medium-term prospect were clouded by an unenviable banking collapse.

All through 2008, as thunderclouds gathered on the horizon, the Central Bank of Iceland, CBI, and the coalition government of social democrats led by the Independence party (conservative) staunchly and with arrogance ignored foreign advice and warnings. Yet, when finally forced to act on October 6 2008, Icelandic authorities did so sensibly by passing an Emergency Act (Act no. 125/2008; see here an overview of legislation related to the restructuring of the banks and here more broadly on economic measures).

Iceland entered an IMF program in November 2008, aimed at restoring confidence and stabilising the economy, in addition to a loan of $2.1bn. In total, assistance from the IMF and several countries amounted to ca. $10bn, roughly the GDP of Iceland that year.

In spite of mostly sensible measures political turmoil and demonstrations forced the “collapse government” from power: it was replaced on February 1 2009 by a left coalition of the Left Green party, led by the social democrats, which won the elections in spring that year. In spite of relentless criticism at the time, both governments progressed in dragging Iceland out of the banking mess.

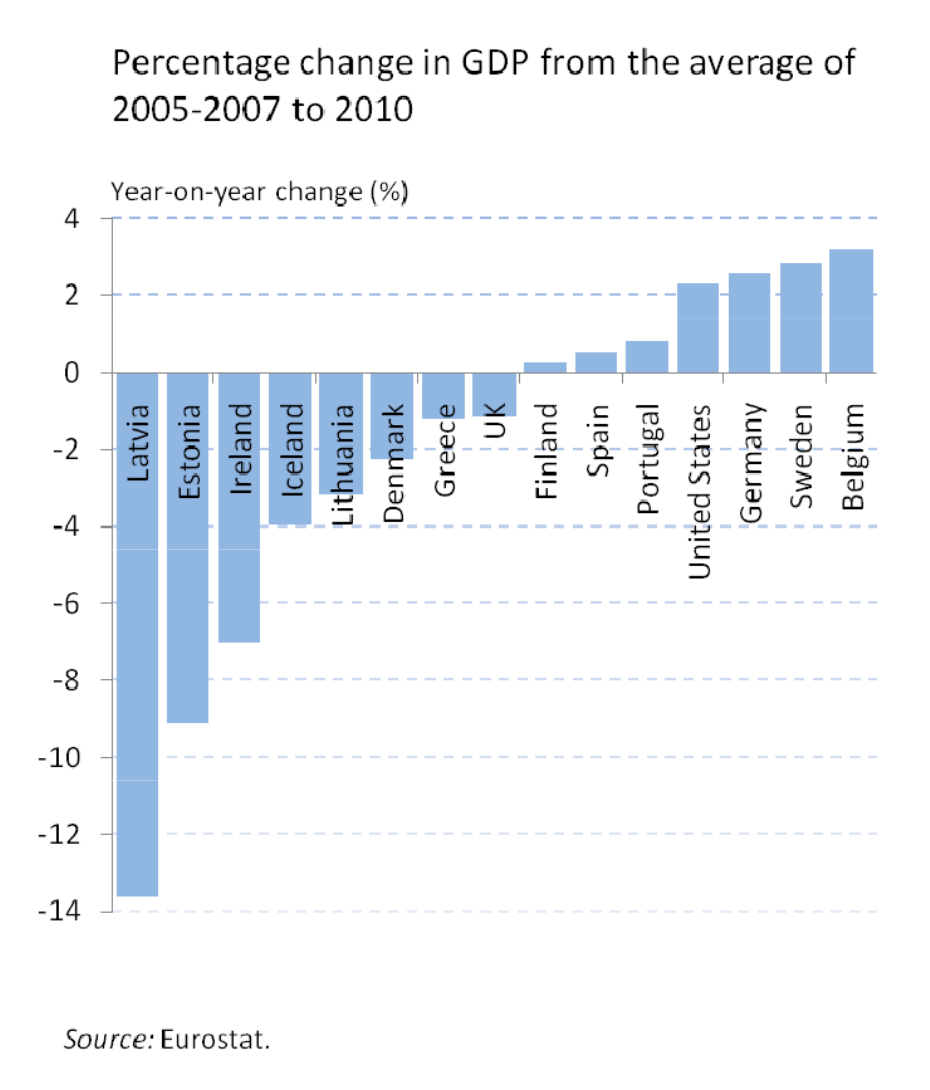

After the GDP contracted by 4% in the first three years the Icelandic economy was already back to growth summer 2011 and is now in its fifth year of economic growth. In 2015, Iceland became the first European country, hit by crisis in 2008-2010, to surpass its pre-crisis peak of economic output.

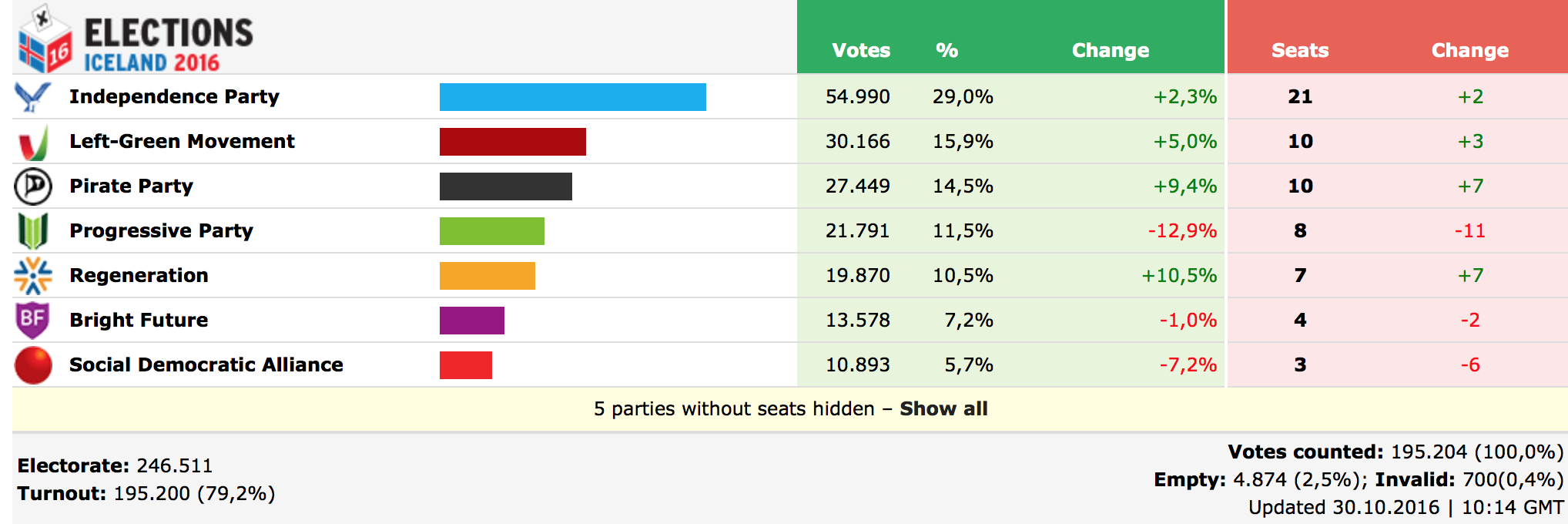

Iceland is now doing well in economic terms and yet the soul is lagging behind. Trust in the established political parties has collapsed: instead, the Pirate party, which has never been in government, enjoys over 30% following in opinion polls.

Compared to Ireland and Greece, Iceland’s recovery has been speedy, giving rise to questions as to why so quick and could this apparent Icelandic success story be applied elsewhere. Interestingly, much of the focus of that debate is very narrow and in reality not aimed at clarifying the Icelandic recovery but at proving or disproving aspects of austerity, the euro or both.

Unfortunately, much of this debate is misleading because it is based on three persistent myths of the Icelandic recovery: that Iceland avoided austerity, did not save its banks and that the country defaulted. All three statements are wrong: Iceland has not avoided austerity, it did save some banks though not the three largest ones and did not default.

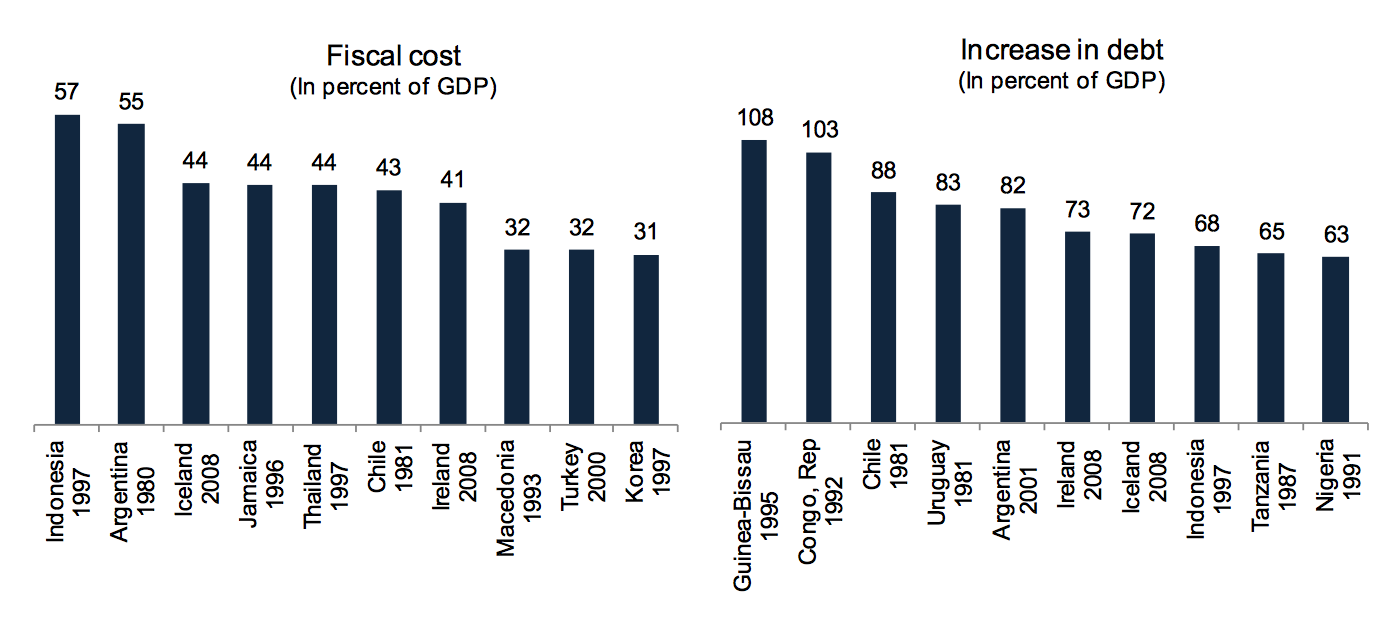

Indeed, the high cost of the Icelandic collapse is often ignored, amounting to 20-25% of GDP. Yet, not as high as feared to begin with: the IMF estimated it could be as much as 40%. The net fiscal cost of supporting and restructuring the banks is, according to the IMF 19.2% of GDP.

Costliest banking crisis since 1970; Luc Laeven and Fabián Valencia.

As to lessons to avoid the kind of shock Iceland suffered nothing can be learnt without a thorough investigation as to what happened, which is why I believe the report, a lesson in itself, by the Special Investigative Commission, SIC, in 2010 was fundamental. Tackling eventual crime, as by setting up the Office of the Special Prosecutor, is important to restore trust. Recovering from a collapse of this magnitude is not only about economic measures and there certainly is no one-trick fix.

On specific issues of the economy it is doubtful that Iceland, a micro economy, can be a lesson to other countries but in general, the lessons are simple: sound public finances and sound public institutions are always essential but especially so in times of crisis.

In general: small economies fall and bounce fast(er than big ones)

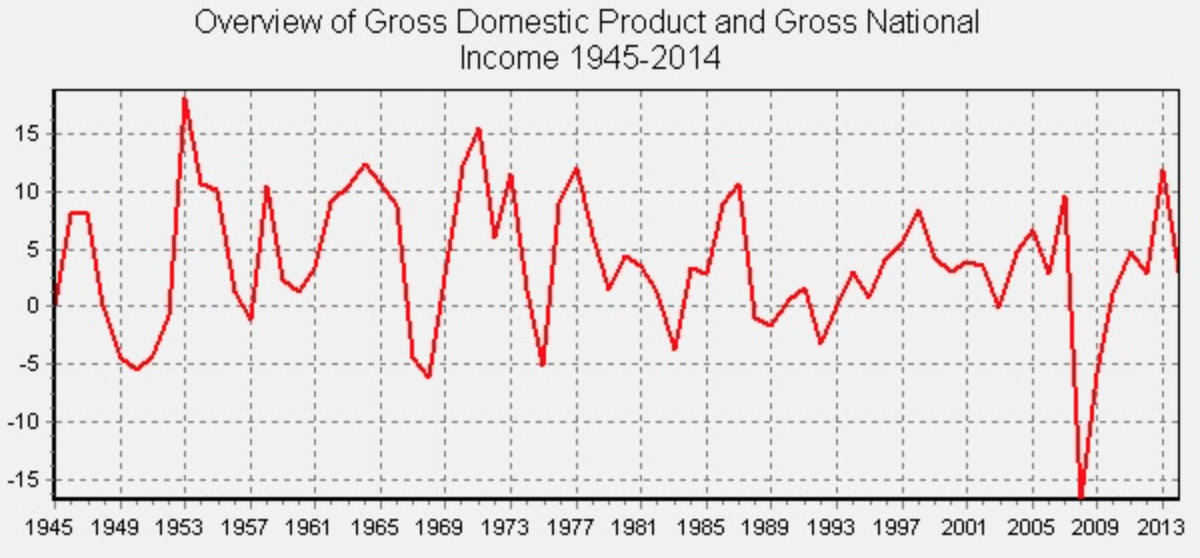

The path of the Icelandic economy over the past fifty years has been a path up mountains and down deep valleys. Admittedly, the banking collapse was a major shock, entirely man-made in a country used to swings according to whims of fishing stocks, the last one being in the last years of the 1990s.

(Statistics, Iceland)

Sound public finances, sound institutions

What matters most in a crisis country? Cleary a myriad of things but in hindsight, if a country is heading for a major crisis make sure the public finances are in a sound state and public authorities and institutions staffed with competent people, working for the general good of society and not special interests – admittedly not a trivial thing.

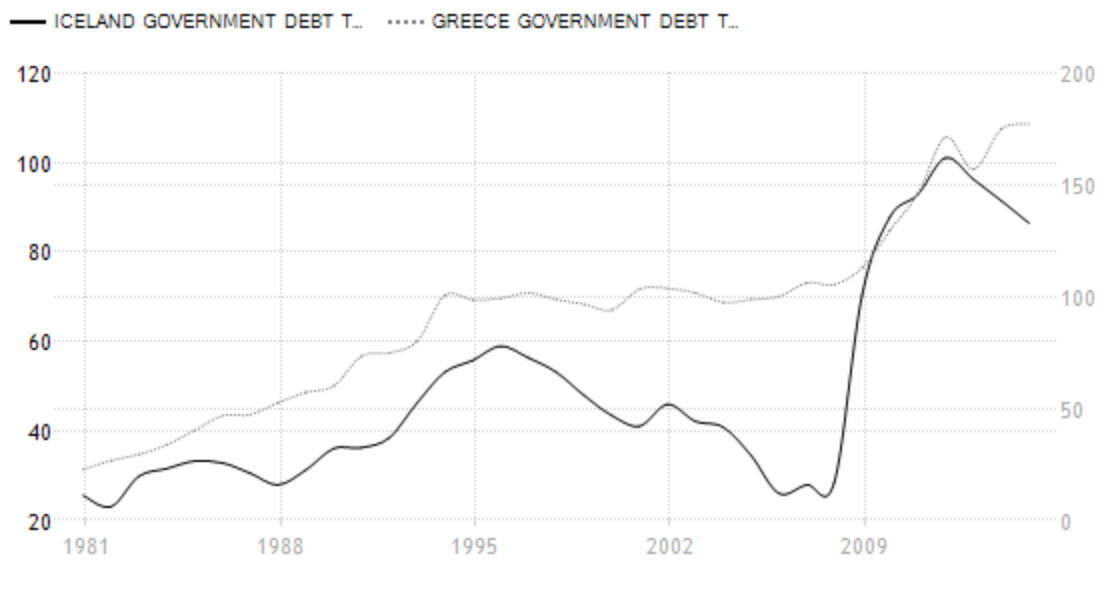

Since 1980 Icelandic sovereign debt to GDP was on average 48.67%, topped at almost 60% around the crisis in late 1990s and had been going down after that. Compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

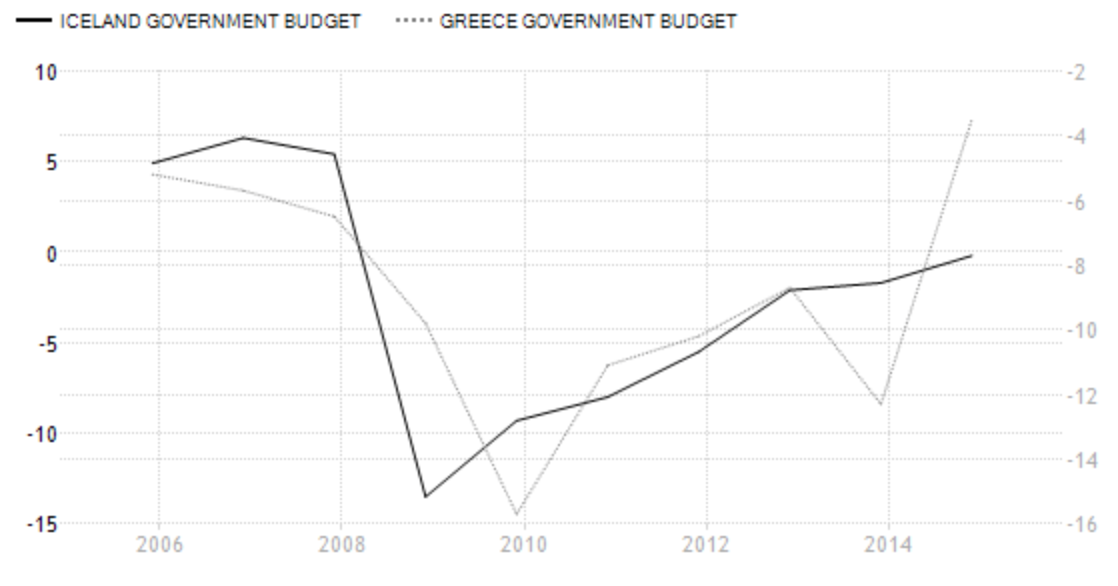

Same with the public budget: there was a surplus of 5-6% in the years up to 2008, against an average of -1.15% of GDP from 1998 to 2014. With a shocking deficit of 13.5% in 2009 it has since steadily improved, pointing to a balanced budget this year and a tiny surplus forecasted for next year. Again, compare with Greece.

Trading Economics

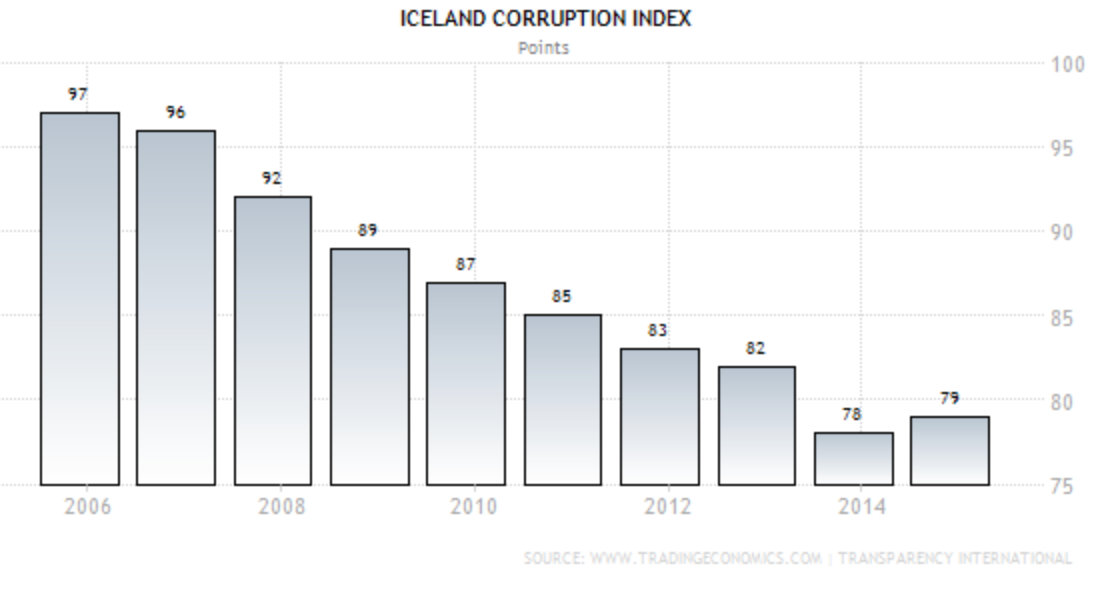

As to institutions, the CBI has been crucial in prodding the necessary recovery policies; much more so after change of board of governors in early 2009. Sound institutions and low corruption is the opposite of Greece, where national statistics were faulty for more than a decade (see my Elstat saga here).

Events in 2008

In early 2007, with sound state finances and fiscal strength the situation in Iceland seemed good. The banks felt invincible after narrowly surviving the mini crisis on 2006 following scrutiny from banks and rating agencies (the most famous paper at the time was by Danske Bank’s Lars Christensen).

Icelanders were keen on convincing the world that everything was fine. The Icelandic Chamber of Commerce hired Frederic Mishkin, then professor at Columbia, and Icelandic economist Tryggvi Þór Herbertsson to write a report, Financial Stability in Iceland, published in May 2006. Although not oblivious to certain risks, such as a weak financial regulator, they were beating the drum for the soundness of the Icelandic economy.

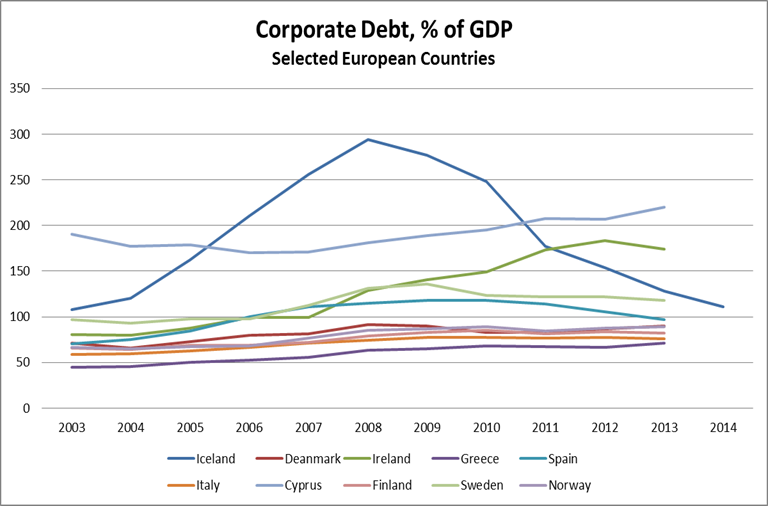

But like in fairy tales there was one major weakness in the economy: a banking system with assets, which by 2008 amounted to ten times the country’s GDP. Among economists it is common knowledge that rapidly growing financial sector leads to deterioration in lending. In Iceland, this was blissfully ignored (and in hindsight, not only in Iceland: Royal Bank of Scotland is an example).

Instead, the banking system was perceived to be the glory of Icelandic policies in a country that had only ever known wealth from the sea. Finance was the new oceans in which to cast nets and there seemed to be plenty to catch.

In early 2008 things had however taken a worrying turn: the value of the króna was declining rapidly, posing problems for highly indebted households – 15% of their loans were in foreign currency, i.a. practically all car loans. The country as a whole is dependent on imports and with prices going up, inflation rose, which hit borrowers; consumer-price indexed, CPI, loans (due to chronic inflation for decades) are the most common loans.

Iceland had been flush with foreign currency, mainly from three sources: the Icelandic banks sought funding on international markets; they offered high interest rates accounts abroad – most of these funds came to Iceland or flowed through the banks there (often en route to Luxembourg) – and then there was a hefty carry trade as high interest rates in Iceland attracted short- and long-term investors.

“How safe are your savings?” Channel 4 (very informative to watch) asked when its economic editor Faisal Islam visited Iceland in early March 2008. CBI governor Davíð Oddsson informed him the banks were sound and the state debtless. Helping the banks would not be “too much for the state to swallow (and here Oddsson hesitated) if it wanted to swallow it.” – Yet, timidly the UK Financial Services Authority, FSA, warned savers to pay attention not only to the interest rates but where the deposits were insured the point being that Landsbanki’s Icesave accounts, a UK branch of the Icelandic bank, were insured under the Icelandic insurance scheme.

The 2010 SIC report recounts in detail how Icelandic authorities ignored or refused advise all through 2008, refused to admit the threat of a teetering banking system, blamed it all on hedge funds and soldiered on with no plan.

The first crisis measure: Emergency Act Oct. 6 2008

Facing a collapsing banking system did focus the minds of politicians and key public servants who over the weekend of October 4 to 5 finally realised that the banks were beyond salvation. The Emergency Act, passed on October 6 2008 laid the foundation for splitting up the banks. Not into classic good and bad bank but into domestic and foreign operations, well adapted to alleviating the risk for Iceland due to the foreign operations of the over-extended banks.

The three old banks – Kaupthing, Glitnir and Landsbanki – kept their old names as estates whereas the new banks eventually got new names, first with the adjective “Nýi,” “new,” later respectively called Arion bank, Íslandsbanki and Landsbankinn. Following the split, creditors of the three banks own 87% of Arion and 95% of Íslandsbanki, with the state owning the remaining share. Due to Icesave Landsbanki was a different case, where the state first owned 81.33%, now 97.9%.

In addition to laying the foundation for the new banks, one paragraph of the Emergency Act showed a fundamental foresight:

In dividing the estate of a bankrupt financial undertaking, claims for deposits, pursuant to the Act on on (sic) Deposit Guarantees and an Investor Compensation Scheme, shall have priority as provided for in Article 112, Paragraph 1 of the Act on Bankruptcy etc.

By making deposits a priority claim in the collapsed banks interests of depositors were better secured than had been previously (and normally is elsewhere).

When 90% of a financial system is swept away keeping payment systems functioning is a major challenge. As one participant in these operations later told me the systems were down for no more than ca. five or ten minutes during these fateful days. All main institutions, except of course the three banks, withstood the severe test of unprecedented turmoil, no mean feat.

The coming months and years saw the continuation of these first crisis measures.

It is frequently stated that Iceland, the sovereign, was bankrupted by the collapse or defaulted on its debt. That is not correct though sovereign debt jumped from ca. 30% of GDP in 2008 until it peaked at 101% in 2012.

IMF and international assistance of $10bn

That fateful first weekend of October 2008 it so happened that there were people from the IMF visiting Iceland and they followed the course of events. Already then seeking IMF assistance was discussed but strong political forces, mainly around CBI governor Davíð Oddsson, former prime minister and leader of the Independence party, were vehemently against.

One of the more surreal events of these days was when governor Oddsson announced early morning on October 7 that Russia would lend Iceland €4bn, with maturity of three to four years, the terms 30 to 50 basis points over Libor. According to the CBI statement “Prime Minister Putin has confirmed this decision.” – It has never been clarified who offered the loan or if Oddsson had turned to the Russians but as the Cypriot and Greek government were to find out later this loan was never granted. If Oddsson had hoped that a Russian loan would help Iceland avoid an IMF program that wish did not come true.

On November 17, 2008 the Prime Minister’s Office published an outline of an Icelandic IMF program: Iceland was “facing a banking crisis of extraordinary proportions. The economy is heading for a deep recession, a sharp rise in the fiscal deficit, and a dramatic surge in public sector debt – by about 80%.”

The program’s three main objectives were: 1) restoring confidence in the króna, i.a. by using capital controls; 2) “putting public finances on a sustainable path”; 3) “rebuilding the banking system… and implementing private debt restructuring, while limiting the absorption of banking crisis costs by the public sector.”

An alarming government deficit of 13.5% was now forecasted for 2009 with public debt projected to rise from 29% to 109% of GDP. “The intention is to reduce the structural primary deficit by 2–3 percent annually over the medium-term, with the aim of achieving a small structural primary surplus by 2011 and a structural primary surplus of 3½-4 percent of GDP by 2012.” – This was never going to be austerity-free.

By November 20 2008 IMF funds had been secured, in total $2.1bn with $827m immediately available and the remaining sum paid in instalments of $155m, subject to reviews. The program was scheduled for two years and the loan would be repaid 2012 to 2015.

Earlier in November Iceland had secured loans of $3bn from the other Nordic countries together with Russia and Poland (acknowledging the large Polish community in Iceland). Even the tiny Faroe Islands chipped in with $50m. In addition, governments in the UK, the Netherlands and Germany reimbursed depositors in Icelandic banks, in all ca. $5bn. Thus, Iceland got financial assistance of around $10bn, at the time equivalent of one GDP, to see it through the worst.

In spite of a lingering suspicion against the IMF, both on the political left and right, there was never the defiance à la greque. Both the “collapse coalition” and then the left government swallowed the bitter pill of an IMF program and tried to make the best of it. Many officials have mentioned to me that the discipline of being in a program helped to prioritise and structure the necessary measures.

Recently, an Icelandic civil servant who worked closely with the IMF staff, told me that this relationship had been beneficial on many levels, i.a. had the approach of the IMF staff to problem solving been an inspiration. Here was a country willing to learn.

Part of the answer to why Iceland did so well is that the two governments more or less followed the course set out in he IMF program. This turned into a success saga for Iceland and the IMF. One major reason for success was Iceland’s ownership of the program: politicians and leading civil servants made great effort to reach the goals set in the program. – An aside to the IMF: if you want a successful program find a country like Iceland to carry it out.

Capital controls: a classic but much maligned measure

For those at work on crisis measures at the CBI and the various ministries there was little breathing space these autumn weeks in 2008. No sooner was the Emergency Act in place and the job of establishing the new banks over (in reality it took over a year to finalise) when a new challenge appeared: the rapidly increasing outflow of foreign funds threatened to sink the króna below sea level and empty the foreign currency reserves of the CBI.

On November 28 the CBI announced that following the approval of the IMF, capital flows were now restricted but would be lifted “as soon as circumstances allow.” De facto, Iceland was now exempt from the principle of freedom of capital movement as this applies in the European Economic Area, EEA. The controls were on capital only, not on goods and services, affected businesses but not households.

At the time they were set, the capital controls kept in place foreign-owned ISK650bn, or 44% of Icelandic GDP, mostly harvest from carry trades. Following auctions and other measures these funds had dwindled down to ISK291bn by the end of February 2015, just short of 15% of GDP. However, other funds have grown, i.e. foreign-owned ISK assets in the estates of the failed banks, now ca. ISK500bn or 25% of GDP.

In addition, there is no doubt certain pressure from Icelandic entities, i.e. pension funds, to invest abroad. The Icelandic Pension Funds Association estimates the funds need to invest annually ISK10bn abroad. Greater financial and political stability in Iceland will help to ease the pressure. (Further to the numbers behind the capital controls and plan to ease them, see my blog here).

With capital controls to alleviate pressure politicians in general have the tendency to postpone solving the problems kept at bay by the controls; this has also been the case in Iceland. The left government made various changes to the Foreign Exchange Act but in the end lacked the political stamina to take the first steps towards lifting them. With up-coming elections in spring 2013 it was clear by late 2012 that the government did not have the mandate to embark on such a politically sensitive plan so close to elections.

In spring 2015, after much toing and froing, the coalition of Independence party led by the Progressive party presented a plan to lift the controls. The most drastic steps will be taken this winter, first to bind what remains from the carry trades and second to deal with the estates, where ca. 80% of their foreign-owned ISK assets will be paid as a “stability contribution” to the state. (I have written extensively on the capital controls, see here). The IMF estimates it might take up to eight years to fully lift the controls.

It is notoriously difficult to measure the effects of capital controls. It is however a well-known fact that with time capital controls have a detrimental effect on the economy, as the CBI has incessantly pointed out in its Financial Stability reports.

In its 2012 overview over the Icelandic program the IMF summed up the benefits of controls:

“… as capital controls restricted investment opportunity abroad, both foreign and local holders of offshore króna found it profitable to invest in government bonds, which facilitated the financing of budget deficit and helped avoid a sovereign financing crisis.” – Considering the direct influence of inflation, due to CPI-indexation of household debt, the benefits also count for households.

Again, measuring is difficult but the stability brought by the controls seems to have helped though the plan to lift them came none too soon. Some economists claim the controls were unnecessary and have only done harm. None of their arguments convince me.

Measures for household and companies

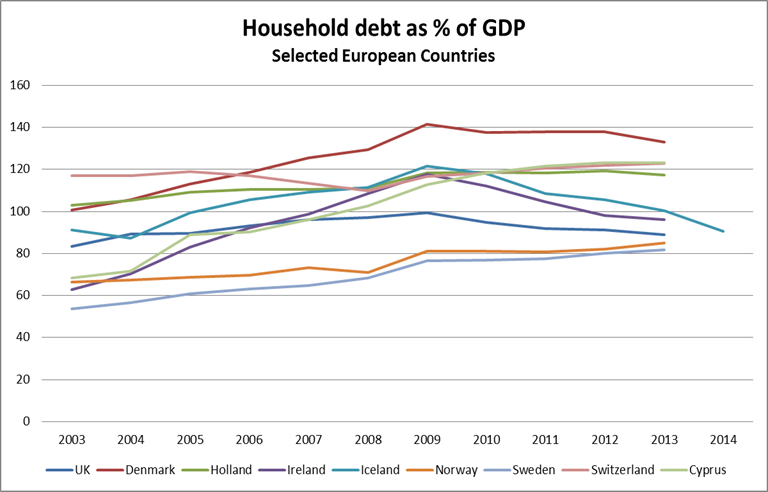

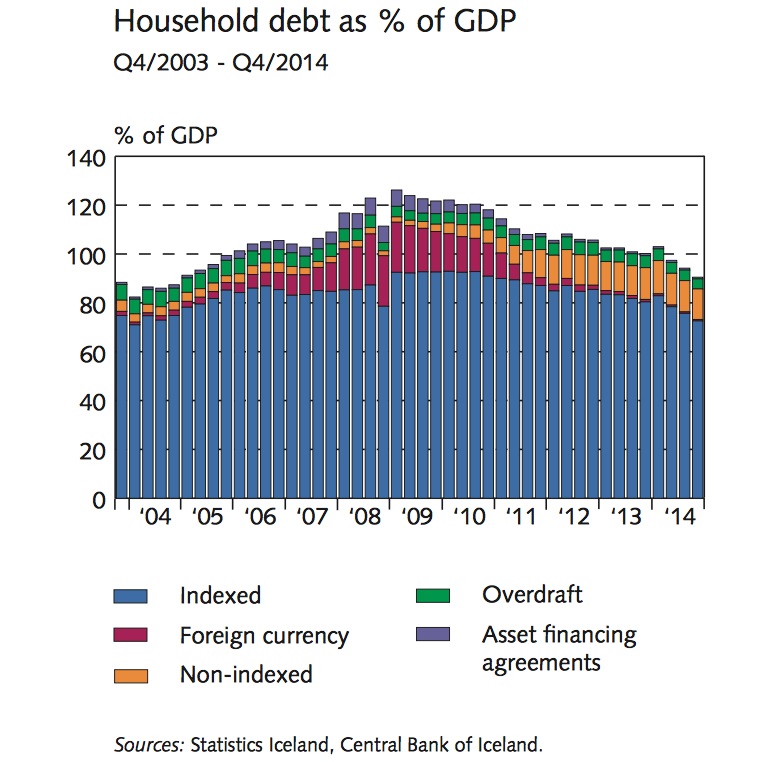

Icelandic households have for decades happily lived beyond their means, i.e. household debt has been high in Iceland. The debt peaked in 2009 but has been going down rapidly since then.

CBI

Already in early 2008, the króna started to depreciate versus other currencies. From October 2007 to October 2008 the changes were dramatic: €1 stood at ISK85 at the beginning of this period but at ISK150 in the end; by October 2009 the €1 stood at ISK185.

Even before the collapse it was clear that households would be badly hit in various ways by the depreciating króna, i.a. due to the CPI-indexation of loans as mentioned above. In addition, banks loaded with foreign currency from the carry trades had for some years been offering foreign currency loans, in reality loans indexed against foreign currencies. With the króna diving instalments shot up for those borrowing in foreign currency; as pointed out earlier, 15% of household debt was in foreign currency.

The left government’s main stated mission was to shield poorer households and defend the welfare system during unavoidable times of austerity following the collapse. In addition, there was also the point that in a contracting economy private spending needed to be strengthened.

The first measure aimed directly at households was in November 2008 when the government announced that people could use private pension funds to pay down debt.

Soon after the banking collapse borrowers with loans in foreign currency turned to the courts to test the validity of these loans. As the courts supported their claims the government stepped in to push the banks to recalculate these loans.

In total, at the end of January 2012 write-downs for households amounted to ISK202bn. For non-financial companies the write-downs totalled ISK1108bn by the end of 2011 (based on numbers from Icelandic Financial Services Association). In general, Icelandic households have been deleveraging rapidly since the crisis.

CBI

Governments in other crisis countries have been reluctant to burden banks with the cost of write-downs and non-performing loans. In Iceland, there was a much greater political willingness to orchestrate write-downs. The fact that foreign creditors owned two of the three banks may also have made it less painful to Icelandic politicians to subject the banks to the unavoidable losses stemming from these measures.

Changes in bankruptcy law

In 2010 the Icelandic Bankruptcy Act was changed. Most importantly, the time of bankruptcy was shortened to two years. The period to take legal action was shortened to six months.

There are exemptions from this in case of big companies and bankruptcy procedures for financial companies are different. However, the changes profited individuals and small companies. In crisis countries such as Greece, Ireland and Spain bankruptcy laws has been a big hurdle in restructuring household finances, only belatedly attended to.

… and then, 21 months later, Iceland was back to growth

It was indicative of the political climate in Iceland that when the minister of finance, trade and economy Steingrímur Sigfússon, leader of the Left Green party, announced in summer 2011 that the economy was now growing again his tone was that of an undertaker. After all, the growth was “only” forecasted to be around 2%, much less than what Iceland had enjoyed earlier. Yet, this was a growth figure most of his European colleagues would have shouted from the rooftops.

Abroad, Sigfússon was applauded for turning the economy around but he enjoyed no such appreciation in Iceland.

As inequality diminished during the first years of the crisis the government could to a certain degree have claimed success (see on austerity below). However, the left government did poorly in managing expectations. Torn by infighting, its political opponents, both in opposition and within the coalition parties never tired of emphasising that no measures were ever enough. That was also the popular mood.

The króna: help or hindrance?

Much of what has been written on the Icelandic recovery has understandably been focused on the króna – if beneficial and/or essential to the recovery or curse – often linked to arguments for or against the EU and the euro.

A Delphic verdict on the króna came from Benedikt Gíslason, member of the capital controls taskforce and adviser to minister of finance Bjarni Benediktsson. In an interview to the Icelandic Viðskiptablaðið in June 2015 Gíslason claimed the króna had had a positive effect on the situation Iceland found itself in. “Even though it (the króna) was the root of the problem it is also a big part of the solution.”

Those who believe in the benefits of own independent currency often claim that Iceland did devalue, as if that had been part of a premeditated strategy. That however was not the case: the króna has been kept floating, depreciating sharply when funds flowed out in 2008. The capital controls slammed the break on, stabilising and slowly strengthening the króna.

Lately, with foreign currency inflows, i.a. from tourism, the króna has further appreciated but not as much as the inflows might indicate: the CBI buys up foreign currency, both to bolster its reserve and to hinder too strong a króna. Thus, it is appropriate to say that the króna float is steered but devaluation, as a practiced in Iceland earlier (up to the 1990s) and elsewhere, has not been a proper crisis tool.

Had Iceland joined the EU in 1995 together with Finland and Sweden, would it have taken up the euro like Finland or stayed outside as Sweden did? There is no answer to this question but had Iceland been in the euro capital controls would have been unnecessary (my take on Icelandic v Greek controls, see here). Would the euro group and the European Central Bank, ECB, have forced Iceland, as Ireland, to save its banks if Iceland had been in the euro zone? Again, another question impossible to answer. After all, tiny Cyprus did a bail-in (see my Cyprus saga here).

On average, fisheries have contributed around 10% to the Icelandic GDP, 11% in 2013 and the industry provided 15-20% of jobs. Fish is a limited resource with many restrictions, meaning that no matter markets or currency fishing more is not an option.

Tourism has now surpassed the fishing industry as a share of GDP. Again, depreciating króna could in theory help here but Iceland is not catering to cheap mass tourism but to a more exclusive kind of tourism where price matters less. Attracting over a million tourists a year is a big chunk for a population of 330.000 but my hunch is that the value of the króna only has a marginal effect, much like on the fishing industry: the country’s capacity to receive tourists is limited.

Currency is a barometer of financial soundness. One of the problems with the króna is simply the underlying economy and the soundness of the governments’ economic policies or lack of it, at any given time. Sound policies have often been lacking in Iceland, the soundness normally not lasting but swinging. Older Icelanders remember full well when the interests of the fishing industry in reality steered the króna, much like the soya bean industry in Argentina.

The króna is no better or worse than the underlying fundamentals of the economy. In addition, in an interconnected world, the ability of a government to steer its currency is greatly limited, interestingly even for a major currency like the British pound. What counts for a micro economy like Iceland is not necessarily applicable for a reserve currency.

Needless to say, the króna did of course have an effect on how Iceland fared after the collapse but judging exactly what that effect has been is not easy and much of what has been written is plainly wrong. (I have earlier written about the right to be wrong about Iceland; more recent example here). In addition, much of what has been written on Iceland and the króna is part of polemics on the EU and the euro and does little to throw light on what happened in Iceland.

Iceland: no bailouts, no austerity?

There have been two remarkably persisting stories told about the Icelandic crisis: 1) it didn’t save its banks and consequently no funds were used on the banks 2) Iceland did not undergo any austerity. – Both these stories are only myths, which have figured widely in the international debate on austerity-or-not, i.a. by Paul Krugman (see also the above examples on the right to be wrong about Iceland) who has widely touted the Icelandic success as an example to follow. Others, like Tyler Cowen, have been more sceptical.

True, Iceland did not save its three largest banks. Not for lack of trying though but simply because that task was too gigantic: the CBI could not possibly be the lender of last resort for a banking system ten times the GDP, spread over many countries.

When Glitnir, the first bank to admit it had run out of funds, turned to the CBI for help on September 29 2008, the CBI offered to take over 75% of the bank and refinance it. It only took a few days to prove that this was an insane plan. The CBI lent €500m to Kaupthing on the day the Alþingi passed the Emergency Act, October 6 2008, half of which was later lost due to inappropriate collaterals. This loan is the only major unexplained collapse story.

The left government later tried to save two smaller banks – a futile exercise, which only caused losses to the state – and did save some building societies. The worrying aspect of these endeavours was the lack of clear policy; it smacked of political manoeuvring and clientilismo and only added to the high cost of the collapse, in international context.

As to austerity, every Icelander has stories to tell about various spending cuts following the shock in October 2008. Public institutions cut salaries by 15-20%, there were cuts in spending on health and education. (Further on cuts see IMF overview 2012).

With the left government focused on the poorer households it wowed to defend benefit spending and interest rebates on mortgages. These contributions are means-tested at a relatively low income-level but helped no doubt fending off widening inequality. Indeed, the Gini coefficients have been falling in Iceland, from 43 in 2007 to 24 in 2012, then against EU average of 30.5. (See here for an overview of the social aspects of the collapse from October 2011, by Stefán Ólafsson).

In addition, it is however worth observing that although inequality in general has not increased, there are indications that inter-generational inequality has increased, as pointed out in the CBI Financial Stability Report nr. 1, 2015: at end of 2013 real estate accounted for 82% of total assets for the 30 to 40 years age group, compared to 65% among the 65 to 70 years old. The younger ones, being more indebted than the older ones are much more vulnerable to external shocks, such as changes in property prices and interest rates. Renters and low-income families with children, again more likely to be young than older people, are still vulnerable groups.

In the years following the crisis the unemployment jumped from 2.4% in 2008 to peak of 7.6% in 2011, now at 4.4%. Even 7.6% is an enviable number in European perspective – the EU-28 unemployment was 9.5% in July 2015 and 10.9.% for the euro zone – but alarming for Iceland that has enjoyed more or less full employment and high labour market participation.

Many Icelanders felt pushed to seek work abroad, mostly in Norway, either only one spouse or the whole family. Poles, who had sought work in Iceland, moved back home. Both these trends helped mitigate cost of unemployment benefits.

Austerity was not the only crisis tool in Iceland but the country did not escape it. And as elsewhere, some have lamented that the crisis was not used better to implement structural changes, i.a. to increase competition.

The pure luck: low oil prices, tourism and mackerel

Iceland is entirely dependent on oil for transport and the fishing fleet is a large consumer of oil. Iceland is also dependent on imports, much of which reflect the price of oil, as does the cost of transport to and from the country. It is pure luck that oil prices have been low the years following the collapse, manna from heaven for Iceland.

The increase in tourism has been crucial after the crisis. Tourism certainly is a blessing but the jobs created are notoriously low-paying jobs. As anyone who has travelled around in Iceland can attest to, much of these jobs are filled not by Icelanders but by foreigners.

Until 2008, mackerel had never been caught in any substantial amount in Icelandic fishing waters: the catch was 4.200 ton in 2006, 152.000 ton in 2012. Iceland risked a new fishing war by unilaterally setting its mackerel quota. Fishing stocks are notoriously difficult to predict and the fact that the mackerel migrated north during these difficult years certainly was a stroke of luck.

The non-measureables: Special Prosecutor and the SIC report

As Icelanders caught their breath after the events around October 6 2008 the country was rife with speculations as to what had indeed happened and who was to blame. There were those who blamed it all squarely on foreigners, especially the British. But the collapse also changed the perception of Icelanders of corruption and this perception has lingered in spite of action taken against individuals. This seems to be changing, yet slowly.

When Vilhjálmur Bjarnason, then lecturer at the University of Iceland, now MP for the Independence party, said following the collape that around thirty men (yes, all males) had caused the collapse, many nodded.

Everyone roughly knew who they were: senior bankers, the main shareholders of the banks and the largest holding companies, all prominent during the boom years until the bitter end in October 2008. Many of these thirty have now been charged, some are already in prison and other fighting their case in courtrooms.

Alþingi responded swiftly to these speculations, by passing two Acts in December: setting up an Office of a Special Prosecutor, OSP and a Special Investigative Committee, SIC to clarify the collapse of the financial sector. These two Acts proved important steps for clearing the air and setting the records straight.

After a bumpy start – no one applied for the position of a Special Prosecutor – Ólafur Hauksson a sheriff from Reykjavík’s neighbouring town Akranes was appointed in January 2009. Out of 147 cases in the process of being investigated at the beginning of 2015, 43 are related to the collapse (the OSP now deals with all serious cases of financial fraud).

The Supreme Court has ruled in seven cases related to the collapse and sentenced in all but one case; Kaupthing’s second largest shareholder and three of the bank’s senior managers are now in prison after a ruling in the so-called al Thani case. – Gallup Iceland regularly measures trust in institutions. Since the OSP was included, in 2010, it has regularly come out on top as the institution enjoying the highest trust.

As to the SIC its report, published on 12 April 2010, counts a 2600 page print version, which sold out the day it was published, with additional material online; an exemplary work in its thoroughness and clarity.

The trio who oversaw the work – its chairman then Supreme Court judge Páll Hreinsson (now judge at the EFTA Court), Alþingi’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and Sigríður Benediktsdóttir then lecturer in economics at Yale (now head of Financial Stability at the CBI) – presented a convincing saga: politicians had not understood the implication of the fast growing banking sector and its expansion abroad, regulators were too weak and incompetent, the CBI not alert enough and the banks egged on by over-ambitious managers and large shareholders who in some cases committed criminality.

How have these two undertakings – the OSP and the SIC – contributed to the Icelandic recovery? I fully accept that the effect, as I interpret it, is subjective but as said earlier: recovery after such a major shock is not only about direct economic measures.

Setting up the OSP has strengthened the sense that the law is blind to position and circumstances; no alleged crime is too complicated to investigate, be it a bank-robbery with a crowbar or excel documents from within a bank. The OSP calmed the minds of a nation highly suspicious of bankers, banks and their owners.

The benefit of the SIC report is i.a. that neither politicians nor special interests can hi-jack the collapse saga and shape it according to their interests. The report most importantly eradicated the myth that foreigners were only to blame – that Iceland had been under siege or attack from abroad – but squarely placed the reasons for the collapse inside the country.

The SIC had a wide access to documents, also from the banks. The report lists loans to the largest shareholders and other major borrowers. This clarified who and how these people profited from the banks, listed companies they owned together with thousands of Icelandic shareholders.

The SIC’s thorough and well-documented saga may have focused the political energy on sensible action rather than wasting it on the blame game. Interestingly, this effect is no less relevant as time goes by. To my mind, the atmosphere both in Ireland and Greece, two countries with no documented overview of what happened and why, testifies to this.

In addition, the report diligently focuses on specific lessons to be learnt by the various institutions affected. Time will show how well the lessons were learnt but at least heads of some of these institutions took the time and effort, with their staff, to study the outcome.

A country rife with distrust and suspicion is not a good place to be and not a good place for business. Both these undertakings cleared the air in Iceland – immensely important for a recovery after such a shock, which though in its essence an economic shock is in reality a profound social shock as well.

I mentioned sound institutions above. Their effect is not easily measureable but certainly well functioning key institutions such as ministries, National Statistics and the CBI have all been important for the recovery.

Lessons?

In its April 2012 Ex Post Evaluation of Exceptional Access Under the 2008 Stand-by Arrangement the IMF came up with four key lessons from Iceland’s recovery:

(i) strong ownership of the program … (ii) the social impact can be eased in the face of fiscal consolidation following a severe crisis by cutting expenditures without compromising welfare benefits, while introducing a more progressive tax system and improving efficiency; (iii) bank restructuring approach allowing creditors to take upside gains but also bear part of the initial costs helped limit the absorption of private sector losses by public sector; and (iv) after all other policy options are exhausted, capital controls could be used on a temporary basis in crisis cases such as Iceland, where capital controls have helped prevent disorderly deleveraging and stabilize the economy.

The above understandably refers to the economic recovery but recovering from a shock like the Icelandic one – or as in Ireland, Greece and Cyprus – is not only about finding the best economic measures, though obviously important. It is also about understanding and coming to terms with what happened.

As mentioned above, I firmly believe that apart from classic measures regarding insolvent banks and debt, both sovereign and private, the need to clarify what happened, as was done by the SIC and to investigate alleged criminality, as done by the OSP, is of crucial importance – something that Ireland (with a late and rambling parliamentary investigation), Greece, Cyprus and Spain could ponder on. All of this in addition to sound institutions and sound public finances before a crisis.

The soul lagging behind

In the olden days it was said that by traveling as fast as one did in a horse-drawn carriage the soul, unable to travel as fast, lagged behind (and became prone to melancholia). Same with a nation’s mood following an economic depression: the soul lags behind. After growth returns and employment increases it takes time until the national mood moves into the good times shown by statistics.

Iceland is a case in point. Although the country returned to growth, with falling unemployment, in 2011 the debate was much focused on various measures to ease the pain of households and nothing seemed ever enough.

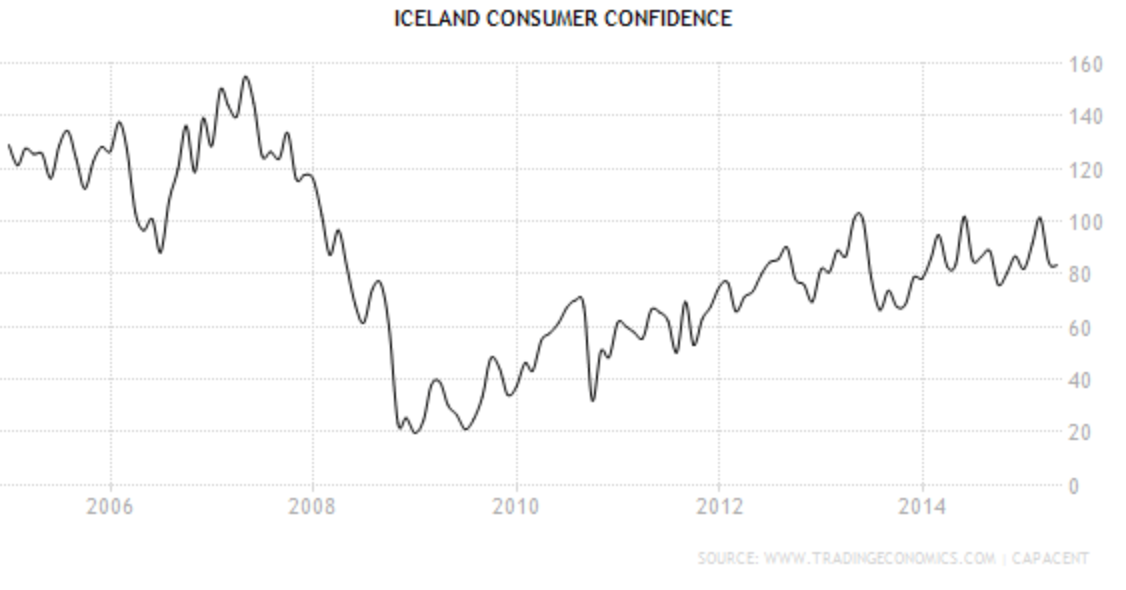

The Gallup Expectations monitor turned upwards in late 2009, after a steep fall from its peak in late 2007, and has been rising slowly since. Yet it is now only at the 2004 level; the Icelandic inclination to spending has been sig-sawing upwards. – Here two graphs, which indicate the mood:

With plan in place to lift capital controls, the last obvious sign of the 2008 collapse will be out of the way. Implementation will take some years; a steady and secure execution this coming winter will hopefully lift spirits in the business community.

Living intimately with forces of nature, volcanoes and migrating fish stocks, and now tourists, as fickle as the fish in the ocean, Icelanders have a certain sangue-froid in times of uncertainty. Actions by the three governments since the collapse have at times been rambling but on the whole they have sustained recovery.

A sign of the lagging soul is that growth has not brought back trust in politics. Politicians score low: the most popular party now enjoying ca. 35% in opinion polls, almost seven years after the collapse and four years since turning to growth, is the Pirate party, which has never been in government.

Recovery (probably) secured – but not the future

As pointed out in a recent OECD report on Iceland the prospect is good and progress made on many fronts, the latest being the plan to lift capital controls: “inflation has come down, external imbalances have narrowed, public debt is falling, full employment has been restored and fewer families are facing financial distress. “

However, the worrying aspect is that in addition to fisheries partly based on cheap foreign labour the new big sector, tourism, is the same. Notoriously low productivity – a chronic Icelandic ill – will not be improved by low-paid foreign labour. Well-educated and skilled Icelanders are moving abroad whereas foreigners moving to the country have fewer skills. Worryingly, there is little political focus on this.

As the OECD points out “unemployment amongst university graduates is rising, suggesting mismatch. As such, and despite the economic recovery, Iceland remains in transition away from a largely resource-dependent development model, but a new growth model that also draws on the strong human capital stock in Iceland has yet to emerge.”

Iceland does not have time to rest on its recovery laurels. Moving out of the shadow of the crisis the country is now faced with the old but familiar problems of navigating a tiny economy in the rough Atlantic Ocean.

This post is cross-posted with A Fistful of Euros.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Myth-busting

It was good to see the FT (paywall) taking up some of the myths of Icelandic recovery. Funnily enough, Icelanders have not been the proponents of the idea that Iceland is some sort of a model. From early on, after the collapse in October 2008, foreign economists have looked to Iceland in search for arguments for their various ideas, often with quite misunderstood facts and/or context.

More on this later – I’ve often mentioned these myths and will do more of it – but I was intrigued to see my Economonitor article, co-written with professor Thorolfur Matthiasson, University of Iceland, quoted by the FT as the work of “two Icelandic experts.” The article shows that the cost to Iceland of the collapse of the banks has indeed been substantial, 20-25% of GDP. There are now 355 tweets and 205 Facebook shares of the Economonitor article so it is far to say it has had a lively distribution.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: successful recovery and the non-bail-out banking myth

Now that so many European countries are struggling, how is Iceland doing? Iceland is doing rather well, thank you. A growth of around 2% is forecasted for this year and the unemployment, though at a horrible high, from the Icelandic point of view, 8% isn’t too bad compared to the neighbouring countries. When reading about Iceland’s good standing, compared to many other countries, the usual refrain is that Iceland didn’t bail out its banks. As shown below, that’s only partially true. Iceland’s economy is indeed weighed down by the cost of its banking crisis.

Iceland’s recovery was the topic of an IMF conference in Reykjavik October 27, most appropriately at Harpa, the new concert house (and since I happened to be in Iceland I was there). Harpa was half-built when the crisis struck but instead of letting it stand as a sad reminder of the insane optimism, it’s now finished, much to the delight of the culturally gluttonous Icelanders.

Martin Wolf from the FT was there and has just published an excellent overview of some of the topics. In addition, he uses the opportunity to show-case Iceland as a good example of a country profiting from not being in the euro. One of the reasons why so many economists seem to be interested in Iceland is that they find there facts and figures to underpin their ideas. Hence, Iceland is quickly becoming all things to many economists.

At Harpa, leading luminaries from the dismal science, such as Willem Buiter and Paul Krugman, pondered on the state of Iceland. But from my point of view, it was most interesting to hear Gylfi Arnbjornsson president of the Confederation of Trade Unions and professor of economy Gylfi Zoega speak, as well as Stefán Olafsson, professor of sociology, both from the University of Iceland. In addition, professor Fridrik Mar Baldursson, Reykjavik University, gave an excellent overview of the Icelandic economy. All this is accessible here.

Arnbjornsson was adamant that with the krona Iceland couldn’t prosper. Export had deteriorated, in spite of sharp depreciation. Such a small open economy wasn’t sustainable with its own currency.

Stefan Olafsson underlined that in spite of cuts, the worst off in society had not lost out the most as seems to be happening elsewhere. The gap between the worst off and those at the top has not widened. This is perhaps the success saga, less that Iceland didn’t save its banks. More on that below.

Gylfi Zoega underlined that it was a fairy tale that Icelanders are different. He characterised Icelandic banking rather well: “others talk about related party lending; we call it banking.”

Jon Danielsson, LSE, argued vehemently against the currency control and has just published an article on the matter, together with Ragnar Arnason, University of Iceland.

But let’s look at this popular belief, running through the IMF conference and most things written on Iceland, that Iceland didn’t bail out its banks. Correct, Iceland didn’t bail out its three large banks that all collapsed in October 2008. The Government tried to safe Glitnir end of September but failed miserably. This attempt made it abundantly clear, that it was, of course, beyond the Central Bank of Iceland to be a lender of last resort for these three, compared to the Icelandic economy, gargantuan institutions. The Government was unable to do anything but watch in horror.

Because these banks failed and weren’t saved, Iceland has become the heroic example of a country that, contrary to ia Ireland, didn’t bail out its banks. So much drivel has been written about this as Grapevine, an Icelandic magazine published in English, pointed out earlier. In this heroic story that’s going around in the world, Iceland didn’t let the debt of private banks migrate from the private to the public sector. I wish this was true but it isn’t. Not quite. Quite some myth-making here.

In the Emergency Act, passed on Oct 6, 2008, there was a provision for helping the Icelandic building societies (similar to the German ‘Sparkassen’). This was later done. Also, the Government helped two banks, VBS and Saga Capital.

With documents from Landsbanki, I have already shown that many years before the crash, Landsbanki kept VBS afloat. Just before Landsbanki collapsed there was the last helping. This kept VBS alive until the following spring when the Government propped it up with ISK26bn (€16.2m), which prolonged its life until early 2010. Together with support to Saga Capital, the Icelandic Government helped these two banks with almost 3% of GDP 2009.

The building-societies system has collapsed, partly because it was taken over – as everything else with a cash flow – by the main banking protagonists, the banks and its main shareholders and clients. The core functions in this system, such as lending, was very unprofitable during the years before the collapse but this fact was masked by prop trading and financial engineering.

In the Icelandic IMF programme, ISK25bn (€15.5m) was set aside to fix the building societies. Out of ten remaining societies, five have been saved by the state. If the cost of saving these banks and a few others are all added it, the amount is over ISK70bn (€43.6m). By adding the cost of saving Sjova, an insurance company, and ILS, the state mortgage company, this bail-out sum rises to ISK118bn (€73.6m) – and that amounts to 7,7% of GDP, not a trivial sum.

But this isn’t the whole story of ‘not bailing out the banks.’ The two main problems from this system of small financial institutions are indeed not small. Byr, horribly abused by Glitnir Bank and its main shareholder Baugur and FL Group, was bought by Islandsbanki (the resurrected Glitnir, now owned by its creditors). Sparisjodur Keflavikur, a building society from Keflavik (yes, where the international airport is) has a huge gaping hole, a string of truly shabby loan stories and was taken over by Landsbanki, owned by the state (the Icesave bank that no creditors want to touch).

These two sales/mergers happened last year but the sales aren’t yet finalised, probably because the state then has to cough up a lot to make these institutions palatable to the new owners. Consequently, these two banks are now a walking danger, zombie banks. The rumour is that just for the Keflavik society, ISK30bn (€18.7) will be needed.

The worst thing is that there doesn’t seem to be any policy in all this bail-out activity. Saving VBS was clear and pure madness and amounted to throwing ISK26bn into the North Atlantic. There might very well be some good reasons to save some of the building societies but there just doesn’t seem to be any clear policy. The Government hasn’t made it clear if all the remaining 10 societies, out of which the state now is a stakeholder in 5, should be run as now, should be merged into one or into a few larger ones.

All in all, Iceland has some ISK200bn (€1.2bn)* at risk in the banking system, ca 14% of GDP. So here is the correct version of bank bail-outs in Iceland: the Icelandic Government at the time couldn’t save the three largest banks – but a lot of the undergrowth in the financial system has been saved. And it’s not clear why or what the policy is.

*The Icelandic number is correct but the conversion into euros was wrong; it should be €1.2bn, as is now stated, not €124.5m as was previously stated.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

COVID-19 in Iceland – medical success (so far) but what do Icelanders really want?

The Icelandic COVID-19 policy was less severe than in Denmark and, belatedly, in the UK. Iceland followed WHO guidelines to test, trace and then isolate – and COVID-19 cases have next to disappeared. The economy was in a healthy state at the beginning of the year, but the economic outlook is now bleak as the country’s three main sources of revenue are facing serious challenges: international tourism has been suspended, the market for fresh fish is seriously hit as restaurants in Iceland’s main markets are closed and price for aluminium is record low. With COVID-19 cases almost extinct, Icelanders are again out and about but now is the time for the existential questions: if Iceland should not aim for something more sustainable for the nation than the windfall of international tourism?

As a nation used to natural disasters, Icelanders have a well-developed rapid reaction team, Almannavarnir, recently tested by COVID-19 – and, as most Icelanders will tell you proudly, the team and the authorities have, so far, done well in beating the virus. The success strategy has been tracking, testing and isolating confirmed cases. One myth has already risen: that every Icelander has been tested. That is not the case but by 7 June, 62,795 tests had been carried out, in a population of 364,000; equivalent to having tested almost 1/6 of the population, probably the highest ration in any country.

The Icelandic name Almannavarnir is familiar to every Icelander and rather more appealing than its English name, Department of Civil Protection and Emergency Management, DCPEM. The Civil Protection responsibilities at the national level are delegated to the National Commissioner of the Icelandic Police, NCIP. This Department, together with Landlæknir, Directorate of Health, DoH, has orchestrated action against the Covid-19 transmission.

The three, by now, famous faces in Iceland leading the virus team – Alma Möller head of DoH, her colleague Þórólfur Guðnason Chief Epidemiologist and Chief Superintendent of the NCIP Víðir Reynisson – conducted daily televised press briefings. To add some fun during the Icelandic lock-down, the COVID-troika joined Icelandic musicians, singing about travelling inside our houses and maybe, if adventurous, camping in the garage. It was not the government but this troika that every day told Icelanders what they could and could not do, gave good advice on mental health and on the whole, informed the nation in a kind and caring way.

Knowing the pattern of social interaction in Iceland, where distances are short, car ownership high and social networks tight, it was not surprising that once the virus was spreading in Iceland – the first case was confirmed on 28 February – the initial transmission was ominously rapid. The policy was to track, test – and then isolate those who were infected.

The measures have not been as drastic as in Denmark and the UK but more severe than in Sweden. The first measures, by mid-March, encouraged social distance and limited social events. By now, June 7, Iceland seems more or less COVID-free; there have been 1807 confirmed cases, with 10 deaths. The webpage covid.19 (also in English) provides information on everything related to the virus in Iceland.

For the time being, anyone arriving in Iceland has to go into quarantine for two weeks. From June 15, anyone arriving in Iceland has the option of paying ISK15,000 (EUR100 / GBP90) or go into quarantine. Tourists are few and far between and their disappearance is already very visible: in April last year, 474,000 tourists visited Iceland; this year they were 3,000, a fall of 99,3%. Icelanders will be able to travel outside their own homes this summer, but they might enjoy the novel experience of mostly having their country to themselves.

A far-away-virus, rapidly very close

At the WHO headquarters in Geneva, the year 2020 began with an alert: on January 1, WHO set up an Incident Management Support Team, responding to an outbreak, reported on the last day of 2019 by Wuhan Municipal Health Commission where doctors had noticed a cluster of pneumonia cases. The first case might have sprung up in early December. On January 12, Chinese authorities had shared the genetic sequence of a new corona virus, Corona Virus Disease 2019 or COVID-19.

On January 13, the first case outside of China was confirmed, in Thailand. On that day the Icelandic DoH put out its first press release on the new virus, also sent to all health institutions in Iceland. The DoH pointed out that both the WHO and European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, ECDC, had published notes on a pneumonia epidemy in Wuhan, caused by a coronavirus, but different from SARS and MERS.

Icelanders were informed that anyone who had been in Wuhan and developed fever and cold should contact a doctor but only if the symptoms were severe. An updated DoH press release that same day added five advices: wash hands; stay away from people who show signs of cold; stay away from animals, also wild animals; sneeze into a handkerchief; contact health workers if symptoms developed after a trip to China.

Late January: Icelandic authorities fully expect the new virus to reach Iceland

On January 24, DoH announced it was responding to the new virus according to Icelandic law and WHO guidelines. Three measures were put in place: 1) Information on hand at Keflavík Airport, for passengers who had been in Wuhan the previous two weeks; 2) Icelandic health institutions were being informed on preparedness. 3) A COVID-19 website with daily updates was opened, both for health workers and the general public.

On January 27, noting the transmission of the new virus to Taiwan, Thailand, Australia, Malaysia, Singapore, France, Japan, South-Korea, US, Vietnam, Cambodia, Nepal, as well as China, DoH underlined that it fully expected the virus to reach Iceland. At the time, there were 2800 confirmed cases worldwide, 2775 in China, the rest in single-digit numbers spread over the other twelve countries.

By January 29 the DoH advice was: don’t travel to Wuhan and avoid all unnecessary travel. On February 24, the focus changed: the COVID risk had reached Europe and DoH now advised against unnecessary travel to four Italian regions: Lombardy, Emilia Romagna, Veneto and Piemonte.

Two days later, the China and the four Italian regions were defined as risk zone. No one should travel there but anyone who had been there recently should go into quarantine. Any non-essential travel to South Korea and Iran should be avoided and those visiting other parts of Italy should take great care as well as those visiting Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong and Tenerife, where thousands of Icelanders, especially older people spend weeks and months over the winter. Also, people were now told to contact doctors by phone if they showed symptoms instead of going to the A&E or other health institutions.

First confirmed COVID-19 case in Iceland: February 28

By late February, the DoH was releasing COVId-information almost daily. On February 27, Icelandic health officials started testing for COVID-19 in Iceland among people who were returning from risk zones. That was also the day when the Icelandic COVID-troika, Alma, Þórólfur and Víðir, held their first press conference, streamed live in the Icelandic media. After testing 111 people on February 27 and 28, an Icelander who had been skiing in Northern Italy was confirmed positive on the 28th.

On February 29, a plane from Verona was met by health workers; passengers showing symptoms were tested. By March 1, there were two additional cases confirmed, again people returning from skiing trips on flights from Verona and Munich. The DoH defined the whole of Italy as a risk zone.

There were now 300 people in quarantine: passengers on the same flights as those, testing positive, were asked to isolate at home for two weeks. Foreigners travelling to Iceland on these flights were not asked to isolate since they would be less likely to interact with Icelanders in care homes and hospitals, the main causes for concern.

DoH was testing avidly: on March 2, 150 were tested, 180 the following day, as part of the program already in place of testing, tracing and isolating.

On March 4 ten people tested positive for COVID-19, bringing confirmed cases to 26. Since all of them had recently returned from Northern Italy and Austria they were already in quarantine. At this point, 380 people were in quarantine and testing facilities were being scaled up. So far, there was no confirmed community transmission of the virus, but the rapidly rising number of infected people was ominous.

Famously, on March 4, prime minister Boris Johnson said at a press conference he had shaken hands with people as he visited a hospital with COVID patients. That day, there were 87 confirmed COVID cases in the UK and rising rapidly.

DCPEM pointed out there was as yet no ban on social gatherings but stressed the importance that those who had been to risk zones respected the advice on quarantine. Contrary to the message Johnson was giving, the DCPEM asked people to avoid touch; no shaking hands or hugging.

Iceland and the Ischgl saga

Icelandic authorities were quick to spot a pattern: Icelandic skiers returning from Ischgl were particularly likely to have caught the virus. DoH added Ischgl to its list of risk zones on March 5. On that same day, the Chief Epidemiologist wrote to Austrian health authorities, pointing out that this popular skiing destination seemed the hot spot for the Icelandic COVID-19 cases.

It turns out that the Icelandic concern was the first indication from abroad to Austrian authorities that something was seriously wrong in the Tyrol skiing village. The Ischgl COVID-19 saga is clearly central in the spread of the virus in Europe: not only skiers from Iceland but also from the other Nordic countries, Germany and the UK, caught the virus there and transported it back home just as Europe was waking up to the fact that not only in Italy was the virus spreading rapidly.

Austrian health authorities later concluded that Ischgl was the largest virus cluster in Austria, infecting as many as 800 Austrians and twice as many foreign visitors, who then transmitted the virus to friends and family on returning home.

Small groups of friends and colleagues seem to have been the major part of the skiers who visited Ischgl, a merry crowd as can be seen on numerous pictures and videos on the internet. Sharing whistles to call for more beverages was part of the fun. This was a very lucrative business for the 1600 inhabitants who during the ski season welcome around 500,000 tourists.

Total denial was the first response from Tyrol authorities to the Icelandic letter: no, there was no indication of the virus spreading in Ischgl; most likely the Icelandic skiers had been infected on the plane, among skiers returning from Italy. – However, the Icelandic authorities were absolutely sure: the travellers had been ill as they boarded or became ill during or immediately after their return trip, which excluded transmission on the plane.

Change of heart: no more “Ibiza of the Alps”

On March 7 health authorities in Tyrol reluctantly confirmed that a bar tender at one of the most popular bars, Kitzloch, had tested positive but their conclusion was that there was no reason for further tests. Instead of seeing the bar tender as a super-spreader, the Tyrolians concluded, with no clear arguments, that it was unlikely he had spread the virus. It took two more days to order Kitzloch closed, on March 9.

By now, pressure on the Ischgl Municipality to react was growing. On March 12, a week after the letter from Iceland, the Ischgl Municipality announced that all ski facilities, hotels and restaurants would close, at least until Mid-May. The next day, the police were guarding road blocks on all roads to the village. And so, the ski season ended early in Tyrol this year, with a lockdown.

The source of contagion in Tyrol has been a hot dispute in Austria: Austrian health authorities now believe that the Patient Zero in Ischgl was a waitress who fell ill already on February 8. Tyrolian authorities have stuck to the story of the first case March 7. British media claim that an Englishman, who visited Ischgl with two friends, fell ill with COVID-19-like symptoms on returning home January 19, as did his two friends, from Denmark and the US. All of them spread the virus in their communities.

The Austrian Consumer Protection Association, VSV is now preparing a class action lawsuit against both public authorities in Tyrol and owners of hotels and bars in the resort; five thousand people, who were in Ischgl at the time of the breakout, have signed up, most of them Germans but also Dutch and British people and one Icelander.

In the European COVID-19 saga, Ischgl has become the prime example of a place where economic interests took precedence to the safety of people, both inhabitants and visitors. Following this sorry saga and the lockdown, the inhabitants of Ischgl have had a rethink: they now want to cater to quality tourism instead of the rowdy party tourism of “Ibiza of the Alps.”

Iceland: ban on social gatherings announced March 11

Back to Iceland where DoH and DCPEM were rapidly preparing measures to come to grips with the transmission. On March 6, when two community transmitted cases were confirmed with no obvious links to travels abroad, a state of emergency was declared but so far, nothing much changed. Not yet.

On March 13 emergency measures were announced, to be in place two days later, from Monday March 16, for four weeks, until Monday April 14. A lockdown yes, but not quite as harsh as the UK lockdown announced whole ten days later, from March 23. From March 16 the general outlines in Iceland were no social gatherings of more than hundred people and 2 metre social distancing.

Schools, from primary schools to universities, could now have no more than 20 pupils in a classroom. The groups were to be segregated at all times, also during breaks, meaning that there had to be staggered lessons and division in all spaces. Nurseries were not restricted by numbers but advised to keep the children in as small groups as possible.

In principle, nothing needed to be locked completely, so long as these measures were met, meaning that restaurants, gyms and swimming pools were still open. Shops were never closed down but had to respect social distancing and crowds, in case of supermarkets.

The deCode testing

deCode is a genomic company, set up in Iceland in 1996, now owned by Amgen. deCode’s operations in Iceland have long been controversial and the same counts for the COVID-screening.

From March 13 people could apply for free screening. It caused some anger when it turned out that the testing site was in the largest office block in the Reykjavík area, where plenty of people still came in to work everyday. Also, those who were tested did not have to sign any informed consent form.

In an article April 14 in the New England Journal of Medicine, co-authored by both the Icelandic Chief Medical Officer, Alma Möller and the Chief Epidemiologist Þórólfur Guðnason, the conclusion is that the virus has infected 0.8% of the population. As known from elsewhere, children under 10 years of age were unlikely to be infected and females less likely than males.

Further, deCode has concluded that 0.5% of Icelanders got infected. Antibody test done by deCode shows however that around 1% of those who were tested but shown not to have the virus and who did not go into quarantine have COVID-19 antibodies. The deCode conclusion is that three times the number of those who were confirmed infected did get the virus and a large number of them did not fall ill. Another finding is that 90% of those who did get infected by the virus have antibodies. Two percent of those who did go into quarantine but tested negative for the virus do have antibodies.

With these results in mind, Amgen lab in Canada is working on a vaccine, partly made from blood from Icelandic COVID-patients. If successful, this vaccine would be used to help patients already ill with the virus.

A biting ban, from March 24

The second and harsher lockdown was announced March 22, due to start two days later: social gatherings of more than twenty people were now banned; the beloved public swimming pools – the Icelandic agora – were now closed, as well as gyms and museums, churches and cinemas and all events and public gatherings forbidden. Any form of public sport or sport in sport clubs was banned as well as work needing physical contact such as hairdressing and massage. Still, restaurants and cafés could remain open but could max have twenty guests, socially distant, at any one time.

Older people were advised to self-isolate as much as possible, staying away from children, grandchildren and other relatives. In Iceland, where family meetings are a large part of people’s social life this meant a huge change. Anecdotal evidence shows that most people followed this religiously, even from early March, before the measures taken.

The modelling

The first COVID-19 casualty in Iceland was on March 16: a tourist who came to the hospital in Húsavík on that day, already severely ill. On March 21, 473 cases of COVID-19 had been diagnosed in Iceland. Ten of them were hospitalised, one in intensive care.

According to a model by Lýðheilsustofnun, the Centre for Public Health, at the University of Iceland, the prognosis was that the disease would peak in early April, with 600 to 1200 cases, thirty to 130 would need to go to hospital and ten to thirty need intensive care. The intensified measures on March 22 were put in place in order to avoid the worst case scenario, which by 23 March were 2000 cases, at a peak in early April, but possibly as many as 4500 (see here on the UoI modelling).

The public policy and people’s efforts have paid off. In total, by 7 June, confirmed COVID-19 cases were 1807. In May there were only seven new cases, in June one so far; 1794 have recovered, 3 were still isolating; 922 are now in quarantine, 21,217 have been in quarantine. In total, there have been 62,795 tests. In a population of 360,000 this level of testing is probably unique. No COVID-19 patient is now in hospital. In total, ten people have died of COVID-19 in Iceland.

Iceland – opening up to a new reality

On April 21 the COVID-troika announced that the first steps towards easing earlier restrictions would be taken on May 4, thus giving schools and businesses the time to prepare. The major change on 4 May was that social gatherings of 50 people were now allowed, up from the previous figure of 20. The luxury of a hair-cut and massage returned. All restrictions on nurseries and schools offering the obligatory education (to age of 16) were lifted. Colleges (from age of 16), universities and other schools could now open.

May 18 was a day of celebration in Iceland: the swimming pools could open on midnight. Many pools did just that, opened at midnight and kept the pool open through the night. People started queueing up early evening.

As of May 25, social gatherings of up to 200 people are again allowed. Gyms are now open and, as the swimming pools, only allowed to take half the number of people they have the license for.

Icelanders are urged to stick to social distancing of 2 metres where possible but the emphasis is now on protecting vulnerable people, whereas the general public should be prudent and take care of itself. Social distancing is no longer a requirement at restaurants, cinemas and theatres, but vulnerable people should be able to require seats with social distance. The Icelandic Symphony Orchestra has already given three public concerts at Harpa, the concert house by the harbour. Families and groups of people could by seats together, but there were two empty seats between each cluster.

For the time being, there is a mandatory two weeks quarantine for everyone coming to Iceland, whether a visitor or living in Iceland. This restriction is due to end 15 June but will be replaced by COVID-19 test at the airport, at ISK15,000 (EUR100 / GBP90), for everyone born before 2005. Those unwilling or unable to pay, will have to go into quarantine.

After introducing the new COVID-19 regime on Monday May 25, after 73 daily meetings, the Icelandic COVID-troika decided the meeting that day should be the last such meeting. Iceland is not entirely back to normal, but the restrictions are less obvious than earlier.

“Two tourists spotted by Mývatn”

By late April, tourists had become a rarity in Iceland as elsewhere. The hotel manager in Mývatn told Rúv that normally at that time of the year he would have been welcoming groups of tourists and new staff, busily preparing for the summer. Instead, the hotel had not had a single guest for a month, but as the headline indicated, he had spotted two tourists in the area. That was all.

In late May, an Icelander sent me a photo of his car at the parking lot by Gullfoss, even in winter always with many buses and cars. This time, his car was the only vehicle there.

As other countries, Icelanders are still trying to figure out what the near future will be like. One thing seems certain: tourists are not out-crowding Icelanders in Iceland this summer. Tourists are few and far between. For those who dream of Iceland like it once was, being alone at Þingvellir or Gullfoss, this is the summer to go to Iceland.

The Icelandic tourist sector is preparing to receive Icelandic customers this summer. Tourist information, mostly available only in English, is being translated into Icelandic. And, from anecdotal evidence, prices are being cut, by as much as a third.

That will be popular among Icelanders who tend to be continuously upset by prices when travelling at home. One commentator said Icelanders were almost too stingy to go swimming when travelling in their home country. Interestingly, Brits travelling in the UK, only spend a third of what they spend once they have left their island; Icelanders might be similar.

Icelanders already planning trips abroad

In addition to Icelandair, SAS, Transavia and Wizz Air have put Iceland on their flight schedule this summer. It seems that from Mid-June there will be plenty of flights to choose from, though obviously nothing like before. The Advantage Travel Partnership, one of many to protest the UK government’s obligatory quarantine for everyone entering the UK from June 8, have put Iceland as number 8 on the list of countries with which they would like to see the UK negotiate an air corridor, with Spain, Greece and Turkey topping the list.

A poll shows that 13% of Icelanders plan to travel abroad already now in summer, with that figure up to 25% in autumn. Half of Icelanders intend to wait until next year, ten percent have no travel plans.

Denmark has lifted travel ban on Norwegian, Finnish and Icelandic tourists, but really does not care to have the Swedes coming over. Iceland is part of the Schengen area, where Germany and many other countries plan on easing travel bans by June 15, also expanding the choice of travel for Icelanders.

The COVID-19 triple whammy on the Icelandic economy

The prospect for the economy is not very bright, mainly because Iceland is very dependent on the economic wellbeing of its main trading partners. The Icelandic crisis benchmark has been the banking collapse in October 2008: after a savage contraction of 6.6% of GDP in 2009 and 4% in 2010, Iceland jumped to 3% growth already in 2011.

Sadly, the COVID-19 hit on the economy might be much worse. In addition, it is a triple whammy hitting the three main Icelandic export sectors: tourism, aluminium production and fish export. Tourism could contract by 27%, aluminium export by 2% and fish export by 8%.

The outlook for last year was a slight contraction of 0.2-0.5%. It now seems the real outcome was rather better, or a growth of GDP of 1.9%. A mid-May forecast (in Icelandic) from Landsbankinn for this year, envisages a contraction of the economy by 9% of GDP, turning into 5% growth in 2021 and 3% the following year, admittedly all with great uncertainty.

Given that tourism, directly and indirectly, has been a major source of employment in Iceland, unemployment has shot up. The forecast for this year is a peak of 13% in summer, 9% by the end of the year, with 7% and 6% in respectively 2021 and 2022. All shockingly high figures for a country that has had a fairly steady employment for the last several years: since summer 2016, unemployment has been hovering around 3%, down from just under 5% in January 2013.

Of other key indicators, the Landsbankinn forecasts big negative movements: private consumption contracting by 7%, import by 23% but balance of payment still positive because of reduced import and hardly any foreign travels.

Nothing like the 2010 Eyjafjalljökull eruption

After the April 2010 eruption of the famous glacier with the unpronounceable name, Icelanders feared the eruption would scare tourists away and devastate the fast-developing Icelandic tourism.

In hindsight, the eruption had the opposite effect: it died out quickly and the spectacular photos captured the imagination. After all, Iceland had already enchanted travel writers and adventurous travellers. The eruption came less than two years after the October 2008 banking collapse, which also created many headlines since Iceland was the first country brought to its knees by the financial crisis. The banking crisis was widely reported on with glorious landscape photos and many foreign journalists gave the Icelandic crisis saga a heroic twist, not recognised in Iceland.

This time, Iceland is not alone to suffer; most countries do, though to a varying degree. But this time, as following the financial crisis, Iceland has a rather good story to tell, actually a much better one than many other countries: the Icelandic authorities did not dither but took action very early. This will all later be scrutinised but though the measures were harsh, it was not a lockdown since schools and nurseries were not completely closed. Iceland certainly slowed down but did not come to a standstill and though the main emphasis was on working from home, most workplaces did remain open.

Now, Iceland can offer virus-weary tourists the possibility to take a vacation in a, so far, relatively safe environment. Some health workers think the government is slightly too keen to open up the country. There is also a hefty debate in Iceland, to some degree similar as the one in Ischgl: do Icelanders really want so many foreign tourists in Iceland? Is this the best path to a sustainable economy? Hopefully this healthy debate might be starting, another saga for another day.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

How is this possible, Greece?

The Greek ELSTAT saga has taken yet another turn, which should be a cause for grave concern in any European country: a unanimous acquittal by three judges of the Greek Appeals Court in the case of former head of ELSTAT Andreas Georgiou has been annulled. This was announced Sunday December 18 – the case was up in court December 6 – but no documents have been published so far, another worrying aspect.