Search Results

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients raise complaints in Luxembourg – updated with a video

At a press conference today, a group of almost 200 clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg in Spain and France raised complaints against the bank, because of its equity release lons and its administrator, Yvette Hamilius, for not investigating what went on in the bank prior to its default. A Brussel-based lawyer, Bernard Maingain, discussed the complaints, most of which Icelog has already written about earlier.

The action taken by the group is both aimed at the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations and the administrator. As Maingain pointed out today, the Landsbanki operations raise many questions – such as if the equity release loans were put together in such a way that they would never make the money promised, if they were mis-sold, if Landsbanki really had the license to operate in Spain and France. It is part of an administrator’s duty to investigate any possible irregularities prior to the failure of the company administrated.

Tomorrow, these claims will be presented in Luxembourg. This is just the beginning of a case, which no doubt will run for a while. The interesting thing is that here Luxembourg is being challenged on its supervision of its gigantic banking sector – the lifeblood of this tiny Duchy. But as representatives of the group said today, they are seeking nothing but justice from Luxembourg.

It will be interesting to see how easy it is to seek justice in a bank-related case in a country utterly and completely at the mercy of its banking sector.

*Here is a video link, in English but mostly in French, on the Landsbanki Luxembourg action, made last week during the press conference in Brussels, with interviews with some Landsbanki clients.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

A legal break for Landsbanki Luxembourg clients in France

A recent ruling in a French court spells out that while a case against Landsbanki Luxembourg for wrongful selling of its products is ongoing in France, Landsbanki Luxembourg cannot pursue its recovery of these loans. Over 80 clients in France of Landsbanki Luxembourg brought a civil case in France against Landsbanki, represented by Yvette Hamilius, for wrongful presentation of its loans. In a ruling July 13, Judge Renaud van Ruymbeke ruled that the recovery could not continue as long as this case is ongoing.

As Icelog has pointed out earlier, so many of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients with equity release loans and often some investments found that incomprehensibly their assets fell just below the value, which demanded they added assets so as to cover 110% of the value. This put many of them in arrears, meaning that the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator started threatening to sell their houses and has indeed sent the bailiffs out.

This French ruling gives them some hope that the selling of the loans, events at Landsbanki before its demise and the consequent actions of the administrator will be clarified.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Remarkable development in Landsbanki Luxembourg

Landsbanki promised “the most comprehensive protection possible” according to the bank’s documentation. That has proved to be very far from the truth. – As reported earlier on Icelog, a group of Landsbanki Luxembourg clients claim they are wrongfully being targeted by the bank’s administrator Mme Yvette Hamilius to pay back dubious “equity release” loans – and in some cases investments, which the bank made without the clients’ knowledge and/or acceptance.

The Icelandic resolution committees for the three Icelandic banks have used time and resources to investigate alleged fraud in the Icelandic banks. The same doesn’t seem to be done in Luxembourg. Icelog has heard evidence from Landsbanki Luxembourg clients, which give good ground to suspect that Landsbanki:

1 Bought the bank’s own bonds, on behalf of clients, without clients’ acceptance, shortly before the bank failed (and at a time when it was most likely already insolvent)

2 Money was taken from clients’ accounts without proper consent for trading

3 MiFID rules were neither applied correctly nor were the clients made aware of these rules and their implications for the clients.

As far as is known, the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator hasn’t done anything to investigate – or have the proper Luxembourg authorities investigate – if this was the case or not. If it is indeed the case that Landsbanki Luxembourg accessed and used clients funds in an inappropriate way it would be most interesting to know who ordered it. Was this a concerted action? And who ordered this allegedly inappropriate use.

In spite of these alleged irregularities, Mme Hamilius seems to treat the clients as if nothing was wrong with the loans and is trying to recover them, going after people’s homes when everything else fails. Most of the clients are elderly and the administrator’s actions and her insufficient communication have put these clients under severe stress and duress by the administrator. An administrator’s business if of course recovery – but an administrator also has the duty to report eventual irregularities and to maintain a reasonable level of communications with those hit by the administrator’s actions.

There are already some legal cases related to Landsbanki clients in France and Spain traversing through court systems there. One couple in Spain have already won their case: their home is now debt free and Landsbanki has to pay them €23.000 in compensation. In spite of this, the Luxembourg administrator carries on as if nothing was happening.

Lately, the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have organised themselves as “Landsbanki Victims Action Group” to put some pressure on Mme Hamilius. They now seem to be making some headway. After issuing a press release on May 7, where they questioned the buisness morale in Luxembourg the local media reported on the Action Group, its plights and a case in France, involving Mme Hamilius. She was interviewed in Paper Jam, a Luxembourg newspaper. Some of her answers there don’t quite fit the reality, seen from the perspective of the clients. The interview was no doubt a reaction to a media action by the clients’ pressure group, reported on in Luxembourg.

But the absolutely most remarkable part of this saga is that on May 8, Robert Biever Procureur Général d’Etat – nothing less than the Luxembourg State Prosecutor – issued a press release, as an answer to the Action Group. It is jaw-droppingly remarkable that a State Prosecutor sees it as a part of his remit to answer a press release that’s pointed against the administrator of a private company. One might think that a State Prosecutor would be unable to comment on a case, which he has neither investigated nor indeed been involved with in any way.

In this surprising move, the Prosecutor puts forth the following claim (in my rough translation; my underlining):

“Following a criminal proceeding in France against Landsbanki Luxembourg November 24 2011 for fraud by the Parisian Justice Van Ruymbeke and without the liquidator accepting the merits of the claims, she offered the borrowers an extremely favourable settlement whereby the borrowers will only reimburse that part of the loans which they received for their personal use, excluding funds used for investments. A considerable number of debtors have now accepted the settlement and the repayment is now being finalised. However, a small number of borrowers are trying with all means to escape their obligations. These are the same people who sent out a press releases on May 7 2012.”*

Apparently, Biever takes such an extreme interest in the case that this civil servant can, the day after the Action Group’s press release (and on the same day it appeared in the Luxembourg media) answer with authority and full certainty. The Prosecutor’s statements raise some questions. How can the State Prosecutor say this is an “extremely favourable settlement”? What makes it favourable? According to my information, it’s indeed not the case that most have paid. How does the Prosecutor know how many have accepted the administrator’s offer? Where did the Prosecutor get that information? If that information came from the administrator, did the Prosecutor verify the numbers?

Since the high office of the Luxembourg State Prosecutor takes such an interest in this case there is perhaps hope that Biever’s curiosity is now sufficiently aroused for him to take a further look at what really happened in Landsbanki Luxembourg in terms of unsound business practice and improper use of funds. I can’t think of any European country where a State Prosecutor would wade into a case of this kind to make a comment. If his comment is made to come to the rescue of the administrator, the functioning of the Luxembourg justice system is light years from the justice system in its neighbouring countries.

Luxembourg makes a good living by being a financial centre. No doubt, its authorities want to emphasis, just like Mme Hamilius does in her interview, that in the little country investment is safe. International creditors should rest assured that no matter what, they will get their money back. This credo seems so important that the State Prosecutor sees it as his role to back up a bank administrator under pressure.

There is indeed a lot to defend in Luxembourg. Monday night (May 14) the BBC programme, Panorama, will “reveal how major UK-based firms cut secret tax deals with authorities in Luxembourg to avoid paying corporation tax in Britain.” – Possibly another worthy case for the Luxembourg State Prosecutor.

*“Suite à l’introduction d’une procédure pénale en France contre Landsbanki Luxembourg et à sa mise en examen le 24 novembre 2011 pour escroquerie par le juge d’instruction parisien Van Ruymbeke, le liquidateur sans pour autant reconnaître le bien fondé des poursuites, a proposé aux emprunteurs des transactions extrêmement favorables aux termes desquelles ceux-ci ne remboursent plus que le capital à eux remis pour leur usage personnel, à l’exclusion des fonds destinés aux investissements. Bon nombre de débiteurs ont d’ailleurs déjà accepté cette proposition et les transactions sont en cours de formalisation. Toutefois un nombre infime d’emprunteurs s’oppose à tout remboursement des fonds reçus et essaye de se soustraire à ses obligations par tous moyens. Ce sont ces mêmes personnes qui sont à l’origine du communiqué de presse du 7 mai 2012.”

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

House searches in Landsbanki Luxembourg

Today (April 17), thirty people – six of them from the Office of the Special Prosecutor in Iceland – have conducted house searches in Luxembourg on behalf of the OSP. The searches have been ongoing at the office of the Landsbanki estate and at two addresses in Luxembourg. According to special prosecutor Olafur Hauksson the searches are connected to nine cases, which surfaced in the media after searches in Iceland in January last year.

As reported on Icelog earlier, the cases under investigation are thought to relate to the following:

1. Alleged market manipulation related to shares in Landsbanki.

2. Loans to four companies Hunslow S.A., Bruce Assets Limited, Pro-Invest Partners Corp and Sigurdur Bollason ehf. to buy shares in Landsbanki.

3. Landsbanki Luxembourg’s sale of loans to Landsbanki only a few days before the bank collapsed in Oct. 2008.

4. The buying of shares by eight offshore companies that supposedly were set up to hold shares related to employees’ options.

The loans to the four companies follow a well-known pattern from the Icelandic banks: huge loans, no collaterals or only the underlying shares being bought in the bank itself – and no apparent intention to have the investors shoulder any risk. All on the bank. It’s always interesting to observe who the benefactors of such loans are since such loans often reveal special relationships behind the banks’ choice of investors.

As pointed out earlier, “Hunslow S.A. was registered in Panama in Feb. 2008. In November 2009 two Novator companies (Novator is the investment fund of Bjorgolfur Thor Bjorgolfsson who was a major shareholder in Landsbanki and Straumur investment bank together with his father) were registered in Panama with the same law firm as Hunslow. The same five directors are on the board of the two Novator companies and Hunslow but there are probably hundreds of companies registered at this one law firm.” This doesn’t prove anything but it’s an intriguing fact.

According to Stoed 2, which broke the news today, Hunslow is owned by Stefan Ingimar Bjarnason, an Icelandic investor, who apart from having profited from Landsbanki’s generosity just before its demise, isn’t a well-known name in Iceland. Bruce Assets is owned by brothers, both known investors in Iceland but no high-flyers, Olafur Steinn and Kristjan Gudmundsson. Only last year did they appear as surprisingly big borrowers at Landsbanki. Interestingly, they invested in companies where Bjorgolfsson was a major investor. The brothers hadn’t been noticed because the loans, in total ISK23bn, all went to offshore companies they owned. The loans to the brothers seemed to have been issued against no collaterals or guarantees. As far as I can see, Bruce Assets is neither registered in Panama nor Luxembourg, can’t see where it’s registered (but would like to know, in case anyone knows).

Prior to the collapse, Sigurdur Bollason was an investor who frequently appeared alongside Jon Asgeir Johannesson and Baugur-related investments. Bollason was a big borrower, without any apparent merit except for strong relations to the banks’ favored circle.

Pro-Invest Partners belongs to a certain Georg Tsvetanski, a long-time business partner of Bjorgolfsson. Tsvetanski is an ex-Deutsche Bank banker. In 2004, he set up the investment fund Altima Partners in the UK together with other Deutsche bankers who specialised in Eastern Europe and who had, during their Deutsche time, cooperated with Bjorgolfsson. Among these are Radenko Milakovic and Dominic Redfern. This group was from from early on involved in Eastern European privatization from 2000, led by or done with Bjorgolfsson: Bulgartabak (which they didn’t get), Balkanpharma (later merged with Actavis), Bulgaria Telecom and in the Czech Republic, Cesky Telecom and Ceske Radiokomunkace.

Early on, Tsvetanski was for while on the board of Pharmaco, the owner of Balkanpharma. As the CEO of the state-owned Balkanpharma he had been a strategic partner. There seems to be an untold story in the privatisation process. Now and then there have been Bulgarian spurts to investigate the matter but so far, it’s never been done. Bjorgolfsson and Altima have also co-invested in Bulgarian properties, through their Luxembourg fund, Landmark.* A rather spectacular golf club and resort, Thracian Cliffs, seems to be a Landmark investment. One of Landmark’s board members is Arnar Gudmundsson, who is at Arena Wealth Management, run by Icelandic ex-bankers, with a very uninformative website. At the end of September 2008, only a week before the bank collapsed, Tzvetanski got an overdraft of ISK4.5bn.

It seems that some of these Landsbanki loans, now being investigated, were issued in Luxembourg. Many of my sources have mentioned that the Landsbanki saga can’t be understood except by mapping out the Luxembourg loans – the source of the dodgiest loans. And that’s where the OSP is at today.

*There is a small galaxy of Landmark companies registered in Luxembourg and some are attached to offshore companies with Icelandic names, ia Keldur Holding Limited, a BVI company and Gort Holding, a Guernsey company.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Luxembourg: a graveyard of financial fraud?

It’s now long since the fateful days in early October when the three main banks in Iceland collapsed, a story well told in an investigative report in April 2010 and on Icelog over the years. However, in Luxembourg untold Icelandic stories still loom, regarding Landsbanki Luxembourg and its equity release loans sold in France and Spain and an entity closely related to Kaupthing and its managers. CSSF, the Luxembourg regulator has kept its blind eye on these stories. But once in a while, the CSSF does rise to act, as a recent decision regarding the afterlife of an investment fund that went into liquidation.

For decades, equity release loans sold mainly to elderly people – often asset rich but cash poor – have caused problems in various countries. Problems, which were not spelled out by the agents, who sold these loans in France and Spain as agents for or on behalf Landsbanki Luxembourg. When the bank collapsed, following the collapse of the mother bank in Iceland, the investment part of these loans were wiped out.

It took the borrowers some years to find out that many of them were experiencing the same problems. The figures didn’t add up and the administrator, Yvette Hamilius, was unwilling to clarify to the borrowers what exactly their positions were. Borrowers claimed they were being told to pay not only what they money they had taken out but the whole loan, with the investment part being ignored. The administrator claimed the borrowers were refusing to pay.

In addition, there seems to be evidence that prior to its collapse, the bank didn’t invest the funds from these loans in an appropriate way.

CSSF: nothing to see, nothing to do

The borrowers have tried to have their cases investigated by the Luxembourg regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF. CSSF has completely ignored the borrowers, in spite of a myriad of court cases related to Landsbanki in Iceland. Also, contrary to administrators of the collapsed banks in Iceland, the Landsbanki Luxembourg administrator allegedly never showed any interest in that side of an administrator’s role.

French authorities investigated Landsbanki’s operations in France in a very strange case, which the prosecutor lost. Strange, because it was investigated very differently from the way banking cases were successfully investigated and prosecuted in Iceland. In Spain, some borrowers have successfully thwarted the administrator’s attempt to seize their homes and houses while other cases have been lost.

In a recent French case related to a Landsbanki equity release loan, the Cour d’Appel d’Aix-en-Provence stated that Landsbanki Luxembourg didn’t have the license to operate in France, ie didn’t have the license to sell these loans but that didn’t necessarily change anything for the borrowers – sounds weird to a non-lawyer but that’s what the Court states.

CSSF did however start to investigate a company called Lindsor, related to Kaupthing’s managers and some of its largest shareholders. Already in 2019, Icelog reported that the case was allegedly fully investigated but that the Luxembourg prosecutor was dithering as to whether to prosecute or not. Long story short: nothing has been heard of this case. Yet another case where Luxembourg could have done something, had indeed spent time and man power on investigations but somewhere in the system, this case seems to have expired for good.

The sense is that in a lilliputian country like Luxembourg, which lives and lives well off its financial sector, safeguarding the sector and not those who do business with that sector seems of major importance.

CSSF: a tiny sign of life

In 2020, Icelog reported on how investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest seemed to be to defend the Duchy’s status as a financial centre, not investigate alleged misdoing within the Duchy’s financial sector. This story was mentioned as a parallel to the travails and tribulations of the Landsbanki Luxembourg borrowers.

Now in February this year, 7 February 2023, in a press release the CSSF stated that in December, it had indeed taken action in that case by imposing an administrative fine of EUR174,400 on the investment fund manager Alter Domus Management Company S.A. (formerly known as Luxembourg Fund Partners S.A.) which took over the administration of a fund, which went into liquidation in early 2017. Interestingly, investors in the funds in question, felt that not all had been well before the liquidation but that the administrator hadn’t paid any attention to their concerns.

The very brief CSSF press release doesn’t go into the details of what happened but the interesting part of the very brief press release is this: “During its investigations, the CSSF identified the existence of material and persistent failures – originating before the liquidation of the SubFund – to comply with the provisions of the Law relating to general requirements on due diligence, on conflicts of interest and in terms of procedures and organisation.”

From the point of view of the borrowers of Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans this is a striking parallel: something wasn’t right before the liquidation, something wasn’t right after it. However, the striking difference is that the fund story was investigated and fine imposed. As the CSSF states this followed an “ad hoc investigations carried out by the CSSF”. Sadly, no ad hoc investigation into Landsbanki Luxembourg and the Lindsor story seems dead.

Icelog has covered these stories extensively in earlier years. Curious readers can find them by searching for key words such as “equity release.” David Mapley has been investing the fund story, mentioned in an Icelog in 2020.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Luxembourg walls that seem to shelter financial fraud

People, mostly pensioners, who previously took out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, have for a decade been demanding that Luxembourg authorities look into alleged irregularities, first with the bank’s administration of the loans, then how the liquidator dealt with their loans after Landsbanki failed. The Duchy’s regulator, CSSF, has staunchly refused to consider this case. Yet, following criminal investigations in Iceland into the Icelandic banks, where around thirty people have been found guilty and imprisoned over the years, no investigation has been opened in Luxembourg into the Duchy operations of the Icelandic banks so far. Criminal investigation in France against the Landsbanki chairman at the time and some employees ended in January this year: all were acquitted. Recently, investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest is defending the Duchy’s status as a financial centre.

Out of many worrying aspects of the rule of law in Luxembourg that the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has exposed, the most outrageous one is still the intervention in 2012 of the State Prosecutor of Luxembourg, Robert Biever. At the time, a group of the bank’s clients, who had taken out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, were taking action against the bank’s liquidator Yvette Hamilius. Then, out of the blue, Biever, who neither at the time nor later, had investigated the case, issued a press release. Siding with Hamilius, Biever stated that a small group of the Landsbanki clients, trying to avoid paying back their loans, were resisting to settle with the bank.

Criminal proceedings in Iceland against managers and shareholders of the Icelandic banks, where around 30 people have been found guilty, show that many of the dirty deals were carried out in Luxembourg. Since prosecutors in Iceland have obtained documents in Luxembourg in these cases, all of this is well known to Luxembourg authorities. Yet, neither the regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, nor other authorities have apparently seen any ground for investigations, with one exception. A case related to Kaupthing has been investigated but, so far, nothing has come out of that investigation (here more on that case, an interesting saga in itself).

However, it now seems that not only the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have their doubts about on whose side the CSSF really is. Investors in a Luxembourg-registered fund claim they were defrauded but that the CSSF has been wholly unwilling to investigate their claims. Their conclusion: the CSSF’s only mission is to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre, which undermines “its responsibility to protect investors.”

That would certainly chime with the experience of the Landsbanki clients. Further, the fact that Luxembourg is a very small country, which greatly relies on its financial sector, might also explain why the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have found it so difficult even to find lawyers in Luxembourg, willing to take on their case.

A slow realisation – information did not add up

It took a while before borrowers of equity release loans from Landsbanki Luxembourg started to suspect something was amiss. The messages from the bank in the first months after the liquidators took over, in October 2008, were that there was nothing to worry about. However, it quickly materialised that there was indeed a lot to worry about: the investments, which had been made as part of the loans, seemed to have been wiped out; what was left was the loan, which had to be paid off.

In addition, there were conflicting information as to the status of the loans, the amounts that had been paid out and the status on the borrowers’ bank accounts. The borrowers, mostly elderly pensioners in France and Spain, many of them foreigners, took out loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, with their properties in these two countries as collaterals. To begin with, they were to begin with dealing with this situation alone, trying to figure out on their own what was going on. It took the borrowers some years until they had found each other and had founded an action group, Landsbanki Victims Action Group.

Landsbanki clients in Spain are part of an action group in Spain against equity release loans, The Equity Release Victims Association, Erva. The Landsbanki clients have taken the Landsbanki estate to court in Spain in order to annul the administrator’s recovery actions there. Lately, the clients have been winning but given that cases can be appealed it might take a while to bring these cases to a closure. The administrator’s attempt to repatriate Spanish court cases against the bank to Luxembourg have, so far, apparently not been successful.

Criminal case in France, civil cases in France and Spain

Finding a lawyer, both for the group and the single individuals who took action on their own, proved very difficult: it has taken a lot of time and effort and been an ongoing problem.

By January 2012, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, had opened an investigation into the loans in France. The French prosecutor lost the case in the Criminal Court of First Instance in Paris in August 2017; on 31 January 2020, the Paris Appeal Court upheld the earlier ruling, acquitting Landsbanki Luxembourg S.A., in liquidation and some of its managers and employees at the time. The case regarded the operations before the bank’s collapse, the administrator was not prosecuted. The Public Prosecutor as well as the borrowers, in a parallel civil case, have now challenged the Paris Appeal Court decision with a submission to the Cour de cassation.

While this case is still ongoing, the administrator’s recovery actions in France were understood to be on hold. According to Icelog sources, that has not entirely been the case.

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity before its demise in October 2008

The main issues with the bank’s marketing and administration of the loans has earlier been dealt with in detail on Icelog but here is a short overview:

As Hamilius mentioned in an interview in May 2012 with the Luxembourg newspaper Paperjam, the loans were sold through agents in Spain and France. After all, the whole operation of the equity release loans depended on agents; Landsbanki Luxembourg was operating in Luxembourg, not in France and Spain.

The use of agents has an interesting parallel in how foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been sold in Europe (see Icelog on FX loans and agents). In the case of FX loans, the Austrian Central Bank deemed that one reason for the unhealthy spread of these risky loans was exactly because they were sold through agents. Agents had great incentives to sell the loans and that the loans were as high as possible but no incentive to warn the clients against the risk. Interestingly, the sale of financial products through agents has been found illegal in some European cases regarding FX loans.*

Other questions relate to how the equity release loans were marketed, i.e. the information given, that the bank classified the borrowers as professional investors, which greatly diminished the bank’s responsibility in informing the clients and also what sort of investments they would choose for the investment part of the loan. Life insurance was a frequent part of the package, another familiar feature in FX loans.

Again, given rulings by the European Court of Justice on FX loans, it seems incomprehensible that the same conditions should not apply to equity release loans as FX loans. After all, there are exactly the same issues at stake, i.e. how the loans were sold, how borrowers were informed and classified (as professional investors though they clearly were not).

How appropriate the investments were for these types of loans and clients is an other pertinent question in this saga. After the collapse of Landsbanki Luxembourg, the borrowers discovered to their great surprise that in some cases the investments were in Landsbanki bonds, even in its shares, as well as in shares and bonds of the two other Icelandic banks, Glitnir and Kaupthing.

That the bank would invest its own loans in the bank’s bonds is simply outrageous. Already in analysis of the Icelandic banks made by foreign banks as early as 2005 and 2006, the high interconnection of the Icelandic banks, was seen as a risk. Thus, if the CSSF had at all had its eyes on these investments, made by a bank operating in Luxembourg, the regulator should have intervened.

It was also equally wholly unfitting to buy bonds in the other Icelandic banks: their credit default swap, CDS, spread made their bonds far from suitable for low-risk investments. – Interestingly, the administrator confirmed in the Paperjam interview 2012 that the loans were indeed invested in short-term bonds of Landsbanki and the two other banks: thus, there is no doubt that this was the case. – Only this fact per se, should have made the liquidator take a closer look at the time.

The value of the properties used as collaterals also raises questions. The sense is that the bank wanted to lend as much as possible to each and every borrower, thus putting a maximum value of the properties put up as collateral.

One of many intriguing facts regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans exposed in the French criminal case was when French borrowers told of getting loan documents in English and English borrowers of getting documents in French. As pointed out earlier on Icelog this seems to indicate a concerted effort by the bank to diminish clarity (at least in some cases, clients were promised they would get the documents in their language of choice, i.e. English borrowers getting documents in English, but the documents never materialised).

Again, this raises serious questions for the CSSF: did the bank adhere to MiFID rules at the time? And did the liquidator really see nothing worth reporting to the CSSF?

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity after its demise in October 2008

After Landsbanki Luxembourg failed in October 2008, Yvette Hamilius and Franz Prost were appointed liquidators for Landsbanki. Following Prost’s resignation in May 2009, Hamilius has been alone in charge. As the Court had originally appointed two liquidators the Court could have been expected to appoint another one after Prost resigned. That however was not the case. Not in Luxembourg. There have been some rumours as to why Prost resigned but nothing has been confirmed.

Be that as it may, the relationship between Hamilius and the borrowers has been a total misery for the borrowers. One of the things that early on led to frustration and later distrust were conflicting and/or unexplained figures in statements. Clarification, both on figures on accounts, and more importantly regarding the investments, was not forthcoming according to borrowers Icelog has heard from.

Hamilius’ opinion of the borrowers could be seen from the Paperjam interview in 2012 and from the remarkable statement from State Prosecutor Biever: the liquidator’s unflinching view was that the borrowers were simply trying to make use of the fact the bank had failed in order to save themselves from repaying the loans.

The interview and the statement from Biever came as a response to when a group of borrowers tried to take legal action against the Landsbanki Luxembourg and its liquidator. In the interview, Hamilius was asked if she was solely trying to serve the interest of Luxembourg as a financial centre, something she staunchly denied.

The action against Landsbanki Luxembourg has so far been unsuccessful, partly because Luxembourg lawyers are noticeably unwilling to take action against a bank, even a failed bank. In that sense, anyone trying to take action against a Luxembourg financial firm finds himself in a double whammy: the CSSF has proved to be wholly unsympathetic to any such claims and finding a lawyer may prove next to impossible.

Why was the investment part of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans killed off?

The key characteristic of equity release loans is that this product consists of a loan and investment, two inseparable parts. However, that proved not to be the case in the Landsbanki Luxembourg loans. Suddenly, after the demise of the bank, the borrowers found themselves to be debtors only, with the investment wiped out. This did fundamentally alter the situation for the borrowers.

The liquidator seems allegedly to have taken the stance that to a great extent, there was nothing to do about the investments in these cases where the bank had invested in Icelandic bank shares and bonds. That is an intriguing point: as pointed out earlier, the bank should never have been allowed to make these investments on behalf of these clients.

In Britain, as in many European countries, the law in general stipulates that if a lender fails, loans are not to be payable right away. As far as I can see, this counts for equity release loans as well: both parts of the loan should be kept going, the loan as well as the investment. Frequently, a liquidator sells off the package at a discount, for another company to administer, in order to be able to close the books of the failed bank.

This has not been the case in Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, the investments were wiped out – and yet, Luxembourg authorities have paid no attention at all to the borrowers’ claims of unfair treatment by the liquidator.

As mentioned above, Hamilius’ version of the sorry saga is that the borrowers are simply unwilling to repay the loan.

The dirty deals of the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg

The recurrent theme in so many of the criminal cases in Iceland after the banking collapse 2008 against bankers and others related to the banks is the role of the banks’ subsidiaries in Luxembourg. The dirtiest parts of the deals were done through the Luxembourg subsidiaries (particularly noticeable in the Kaupthing cases). Since Hamilius has assisted investigations into Landsbanki in Iceland, she will be perfectly well aware of the Icelandic cases related to Landsbanki.

The administrators of the Icelandic banks in Iceland were crucial in providing material for the criminal proceedings in Iceland. Yet, as far as can be seen, the administrator has allegedly not deemed it necessary to take a critical look at the Landsbanki operations in Luxembourg. Which is why no questions regarding the equity release loans have been raised by the administrator with Luxembourg authorities.

The incredibly long winding-up saga at Landsbanki Luxembourg

One interesting angle of the winding-up of Landsbanki Luxembourg saga is the time it is taking. The administrators (winding-up boards) of the three large Icelandic banks, several magnitudes larger than Landsbanki Luxembourg, more or less finished their job in 2015, after which creditors took over the administration of the assets, mostly to sell them off for the creditors to recover their funds. The winding-up proceedings of LBI ehf., the estate of Landsbanki Iceland, came to an end in December 2015, when a composition agreement between LBI ehf. and its creditor became effective.

For some years now, the LBI ehf has been the only creditor of Landsbanki Luxembourg, i.e. all funds recovered by the liquidator go to LBI ehf. Formally, LBI ehf has no authority over the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate. Yet, it is more than an awkward situation since LBI ehf is kept in the waiting position, while the liquidator continues her actions against the equity release borrowers, whose funds are the only funds yet to be recovered.

That said, Luxembourg is not unused to long winding-up sagas. The fall of the Luxembourg-registered Bank of Credit and Commerce International, BCCI, in 1991, was one of the most spectacular bankruptcies in the financial sector at the time, stretching over many countries and exposing massive money laundering and financial fraud. Famously, the winding-up took well over two decades, depending on countries. Interestingly, Yvette Hamilius was one of several administrators, in charge of the process from 2003 to 2011; the winding-up was brought to an end in 2013.

The CSSF on a mission to protect its financial sector, not investors

Recently, another case has come up in Luxembourg that throws doubt on whose interest the CSSF mostly cares for: the financial sector it should be regulating or investors and deposit holders. A pertinent question, as pointed out in an article in the Financial Times recently (23 Feb., 2020), since Luxembourg is the largest fund centre in Europe, with €4.7tn of assets under management and gaining by the day as UK fund managers shift business from Brexiting Britain to the Duchy.

The recent case seems to rotate around three investment funds – Columna Commodities, Aventor and Blackstar Commodities – domiciled in Luxembourg, sub funds of Equity Power Fund. As early as 2016, the CSSF had expressed concern about the quality of the investments: astoundingly, 4/5 of the investments were concentrated in companies related to a single group. Lo and behold, this all came crashing down in 2017.

The investors smelled rat and contacted David Mapley at Intel Suisse, a financial investigator who specialises in asset recovery. Mapley has a success to show: in 2010 he won millions of dollars from Goldman Sachs on behalf of hedge funds, which felt cheated by the bank.

In order to gain insight into the Luxembourg operations, Mapley was appointed a director of LFP I, one of the investment funds in the Equity Power Fund galaxy. (Further on this story, see Intel Suisse press release August 2018 and coverage by Expert Investor in January and October 2019.)

According to the FT, the directors of LFP I claim the CSSF has not lived up to its obligation under EU law. They have now submitted a complaint against the CSSF to European Securities and Markets Authority, Esma, which sets standards and supervises financial regulators in the EU.

In a letter to Esma, Mapley states that the CSSF’s “marketing mission to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre” has undermined its focus on protecting investors. Mapley also alleges the CSSF has attempted to quash the directors’ investigations into mismanagement and fraud by the funds’ previous managers and service providers in order to undermine the funds’ efforts “and prevent any reputational risk”. – That is, the reputational risk of Luxembourg as a financial centre.

As FT points out, investors in a Luxembourg-listed fund that invested in Bernard Madoff’s $50bn Ponzi scheme have also accused the CSSF of leniency, i.e. sheltering the fraudster and not the investors.

Luxembourg, the stain on the EU that EU is unwilling to rub off

Worryingly, the CSSF’s lenient attitude might be more prominent now than ever as Luxembourg competes with other small European jurisdictions of equally doubtful reputation such as Cyprus and Malta (where corrupt politicians set about to murder a journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, investigating financial fraud; brilliant Tortoise podcast on the murder inquiry) in attracting funds leaving the Brexiting UK. Esma has been given tougher intervention powers, though sadly watered down from the original intension, in order to hinder a race to the bottom. It is very worrying that the EU does not seem to be keeping an eye on this development.

As long as this is the case, corrupt money enters Europe easily, with the damaging effect on competition, businesses, politics – and ultimately on democracy.

*Foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been covered extensively on Icelog, see here. For a European Court of Justice decision in the first FX loans case, see Árpád Kásler and Hajnalka Káslerné Rábai v OTP Jelzálogbank Zrt, Case C‑26/13.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Rowland’s Banque Havilland fined €4 million by CSSF

The year of 2018 did not end on a happy note at Banque Havilland: on 21 December 2018 the Luxembourg financial authority, CSSF, fined the bank €4m for non-compliance regarding law on money laundering and terrorist financing, “severe findings” according to the CSSF statement, discovered because of an on site inspection:

Banque Havilland S.A. did not comply with professional obligations with regard to the implementation of a robust central administration and sound and prudent business management and to internal governance arrangements as well as the fight against money laundering requirements.

It is worth remembering that Havilland is the bank David Rowland and his son Jonathan, via the Rowland’s investment fund Blackfish Capital, set up after buying the Kaupthing Luxembourg operations, following the default of the Icelandic Kaupthing.

It was intriguing to see that the Rowlands kept the Kaupthing management in place, this was a smooth transition at the time, nourishing speculation in Iceland that the Kaupthing top management was not far away from it all. However, the Blackfish Capital employee Martyn Konig, who became the CEO of Havilland when the bank opened in 2009, only stayed in the job for a few days before resigning. After his resignation, Jonathan Rowland has been in charge of the bank.

It’s also been duly noted in Iceland that in the many criminal cases in Iceland regarding Kaupthing (all concerning action before the bank defaulted in October 2008), where the Kaupthing top management has been found guilty in several cases as well as large shareholders such as Ólafur Ólafsson, all the questionable deals, without exception, were carried out in Luxembourg. Indeed, the Icelandic Prosecutor, investigating these cases, has conducted several house searches at Banque Havilland, searching for material concerning its previous incarnation as Kaupthing Luxembourg.

As I’ve pointed out time and again, the Luxembourg authorities are fully informed on all investigations going on in Iceland. One case re Kaupthing has been investigated in Luxembourg, the so-called Lindsor case. Lindsor was a BVI company, owned by some Kaupthing employees.

Amongst other things, Lindsor seems to have bought bonds from Skúli Þorvaldsson, a Luxembourg-based businessman and a large client of Kaupthing, and from key employees on the “bank collapse day” 6 October 2008. On that day, the Icelandic Central Bank issued an emergency loan to Kaupthing of €500m, then ISK80bn – of these funds, ISK28bn were used in the Lindsor transaction, effectively moving this sum to Kaupthing insiders and Þorvaldsson (see my blogs concerning the Lindsor case).

So far, no news of the Lindsor investigation have come forth in Luxembourg, while some of those involved have been sentenced to long prison-sentences in Iceland. Incidentally, tomorrow 16 January, a Kaupthing-related case, the so-called Marple case, is coming to appeal court in Iceland, the Country Court (see my blogs concerning the Marple case).

Considering the history of Banque Havilland and the reputation of the Rowlands, it is very interesting to notice the severe fine from the CSSF. If this indicates any turn of events remains to be seen. We are still waiting for the Lindsor investigation (not to mention the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, another Luxembourg saga extensively covered on Icelog).

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The unsolved case of Landsbanki in dirty-deals Luxembourg / 10 years on

The Icelandic SIC report and court cases in Iceland have made it abundantly clear that most of the questionable, and in some cases criminal, deals in the Icelandic banks were executed in their Luxembourg subsidiaries. All this is well known to authorities in Luxembourg who have kindly assisted Icelandic counterparts in obtaining evidence. One story, the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, still raises many questions, which Luxemburg authorities do their best to ignore in spite of a promised investigation in 2013. Some of these questions relate to the activities of the bank’s liquidator, ranging from consumer protection, the bank’s investment in the bank’s own bonds on behalf of clients and if the bank set up offshore companies for clients without their consent.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans were issued to clients in France and Spain. Indeed, all these loans were issued to clients outside of Luxembourg. One intriguing fact emerged during the French trial in Paris last year against Landsbanki Luxembourg and nine of its executives and advisors: the French clients got the bank’s loan documents in English, the non-French clients got theirs in French.*

Landsbanki Iceland went into administration October 7 2008. The next day, Landsbanki Luxembourg was placed into moratorium; liquidation proceedings started 12 December. Over the years, Icelog has raised various issues regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, mostly sold to elderly people (see here). These issues firstly relate to how the bank handled these loans, both the marketing and the investments involved and secondly, how the liquidator Yvette Hamilius, has handled the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate and the many complaints raised by the equity release clients.

A liquidator is an independent agent with great authority to investigate. There is abundant material in Iceland, both from the 2010 Report of the Special Investigative Commission, SIC and Icelandic court cases where almost thirty bankers and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison. These cases have invariably shown that the most dubious deals were done in the banks’ Luxembourg operations.

Already by June 2015, liquidators of the estates of the three large Icelandic banks were ending their work, handing remaining assets over to creditors. In the, in comparison, tiny estate of Landsbanki Luxembourg there is no end in sight due to various legal proceedings. Yet, its arguably largest problem, the so-called Avens bond, was solved already in 2011. At the time, Már Guðmundsson governor of the Icelandic Central Bank paid tribute to the help received from amongst others Hamiliusfor “considerable efforts in leading this issue to a successful conclusion.”

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release clients have another story to tell, both in terms of their contacts with the liquidator and Luxembourg authorities. In May 2012, these clients, who to begin with had each and everyone been struggling individually, had formed an action group and aired their complaints in a press release, questioning Luxembourg’s moral standing and Hamilius’ procedures.

The following day, the group got an unexpected answer: Luxembourg State Prosecutor Robert Biever issued a press release. As I mentioned at the time, it was jaw-droppingly remarkable that a State Prosecutor saw it as his remit to address a press release directed at the liquidator of a private company in a case the Prosecutor had not investigated. According to Biever, Hamilius had offered the borrowers “an extremely favourable settlement” but “a small number of borrowers,” unwilling to pay, was behind the action.

In 2013 Luxembourg Justice Minister promised an investigation into the Landsbanki products that was already taking “great strides.” So far, no news.

The Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release scheme: high risk, rambling investments

In theory, the magic of equity release loans is that by investing around 75% of the loan the dividend will pay off the loan in due course. I have seen calculations of some of the Landsbanki equity release loans that make it doubtful that even with decent investments, the needed level of dividend could have been reached – the cost was simply too high.

If something seems too good to be true it generally is. However, this offer came not from a dingy backstreet firm but from a bank regulated and supervised in Luxembourg, a country proud to be the financial centre of Europe. And Landsbanki was not the only bank offering these loans, which interestingly have long ago been banned or greatly limited in other countries. In the UK, equity release loans wrecked havoc and created misery some decades ago, leading to a ban on putting up the borrower’s home as collateral.

Having scrutinised the investments made for some of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients the first striking thing is an absolutely staggering foreign currency risk, also related to the Icelandic króna. Underlying bonds on the foreign entities such as Rabobank and European Investment Bank were nominated in Icelandic króna (see here on Rabobank ISK bond issue Jan. 2008), in addition to the bonds of Kaupthing and Landsbanki, the largest and second largest Icelandic banks at the time.

Currencies were bought and sold, again a strategy that will have generated fees for the bank but was of dubious use to the clients.

The second thing to notice is the rudderless investment strategy. To begin with the money was in term deposits, i.e. held for a fixed amount of time, which would generate slightly higher interest rates than non-term deposits. Then shares and bonds were bought but there was no apparent strategy except buying and selling, again generating fees for the bank.

The equity release clients were normally not keen on risk but the investments were partially high risk. The 2007 and 2008 losses on some accounts I have looked have ranged from 10% to 12%. These were certainly testing years in terms of investment but amid apparently confused investing there was indeed one clear pattern.

One clear investment pattern: investing in Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds

Having analysed statements of four clients there is a recurring pattern, also confirmed by other clients and a source with close knowledge of the bank’s investments: in 2008 (and earlier) Landsbanki Luxembourg invariably bought Landsbanki bonds as an investment for clients, thus turning the bank’s lending into its own finance vehicle. In addition, it also bought Kaupthing bonds. The 2010 SIC report cites examples of how the banks cooperated to mitigate risk for each other.

It is not just in hindsight that buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds as equity release investment was a doomed strategy. Both banks had sky-high risk as shown by their credit default swap, CDS. The CDS are sort of thermometer for banks indicating their health, i.e. how the market estimates their default risk.

The CDS spread for both banks had for years been well below 100 points but started to rise ominously in 2007 as the risk of their default was perceived to rise. At the beginning of 2008, the CDS spread for Landsbanki was around 150 points and 300 points for Kaupthing. By summer, Kaupthing’s CDS spread was at staggering 1000 points, then falling to 800 points. Landsbanki topped close to 700 points. The unsustainably high CDS spread for these two banks indicated that the market had little faith in their survival. With these spreads, the banks had little chance of seeking funds from institutional investors (SIC Report, p.19-20).

The red lights were blinking and yet, Landsbanki Luxembourg staff kept on steadily buying Landsbanki and Kaupthing bonds on behalf of clients who were clearly risk-averse investors.

Equity release investment in some details

To give an idea of the investments Landsbanki Luxembourg made for equity release borrowers, here is some examples of investment (not a complete overview) for one client, Client A:

Loan of €2.1m in January 2008; the loan was split in two, each half converted into Swiss francs and Japanese yens. The first investment, €1.4m, two thirds of the loan,was in LLIF Balanced Fund (in Landsbanki Luxembourg loan documents the term used is Landsbanki Invest. Balanced Fund 1 Cap but in later overviews from the liquidator it is called LLIF Balanced Fund, a fund named in Landsbanki’s Financial Statements 2007 as one of the bank’s investment funds).

Already in February 2008 Landsbanki Luxembourg bought Kaupthing bond for this client for €96.000. End of April 2008 €155.000 was invested in Landsbanki bond, days before €796.000 of the LLIF Balanced Fund investment was sold. Late May and end of August Landsbanki bonds were bought, in both cases for around €99.000. In early September 2008 Landsbanki invested $185.000 in Kaupthing bonds for this client. The next day, the bank sold €520.000 in LLIF Balanced Fund.

Landsbanki’s investments were focused on the financial sector that in 2008 was showing disastrous results. For client A the bank bought bonds in Nykredit, Rabobank, IBRD and EIB, apparently all denominated in Icelandic króna. In addition, there were shares in Hennes & Maurits, and a Swedish company selling food supplement.

A similar pattern can be seen for the other clients: funds were to begin with consistently invested in LLIF Balanced Fund but later sold in favour of Kaupthing and Landsbanki bonds. Although investment funds set up by the Icelandic banks were later shown to contain shares in many of the ill-fated holding companies owned by the banks’ largest shareholders – also the banks’ largest borrowers – a balanced fund should have been seen as a safer investment than bonds of banks with sky-high CDS spreads.

MiFID and the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans

Landsbanki certainly did not invent equity release loans. These loans have been around for decades. Much like foreign currency, FX, loans, a topic extensively covered by Icelog, they have brought misery to many families, in this case mostly elderly people. FX lending has greatly diminished in Europe, also because banks have been losing in court against FX borrowers for breaking laws on consumer protection.

There might actually be a case for considering the equity release loans as FX loans since the loans, taken in euros, were on a regular basis converted into other currencies, as mentioned above. – This is, so far, an unexplored angle of these cases that Luxembourg authorities have refused to consider.

Another legal aspect is that the first investments were normally done before the loans had been registered with a notary, as is legally required in France.

The European MiFID, Markets in Financial Instruments Directive was implemented in Luxembourg and elsewhere in the EU in 2007. The purpose was to increase investor protection and competition in financial markets.

Consequently, Landsbanki Luxembourg was, as other banks in the EU, operating under these rules in 2007. It is safe to say, that the bank was far below the standard expected by the MiFID in informing its clients on the risk of equity release loans.

The following paragraph was attached to Landsbanki Luxembourg statements: “In the event of discrepancies or queries, please contact us within 30 days as stipulated in our “General Terms and Conditions.”– However, the bank almost routinely sent notices of trades after the thirty days had passed.

It is unclear if the liquidator has paid any attention to these issues but from the communication Hamilius has had with the equity release clients there is nothing to indicate that she has investigated Landsbanki operations compliance with the MiFID. MiFID compliance is even more important given that courts have been turning against equity release lenders in Spain due to lack of consumer protection – and that banks have been losing in courts all over Europe in FX lending cases.

Clients offshorised without their knowledge

The “Panama Papers” revealed that Landsbanki was one of the largest clients of law firm Mossack Fonseca; it was Landsbanki’s go-to firm for setting up offshore companies. Kaupthing, no less diligent in offshoring clients, had its own offshore providers so the leak revealed little regarding Kaupthing’s offshore operations. The prime minister of Iceland Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, who together with his wife owned a Mossack Fonseca offshore company, became the main story of the leak and resigned less than 48 hours after the international exposure.

In September 2008, a Landsbanki Luxembourg client got an email from the bank with documents related to setting up a Panama company, X. The client was asked to fill in the documents, one of them Power of Attorney for the bank and return them to the bank. The client had never asked for this service and neither signed nor sent anything back.

In May 2009, this client got a letter from Hamilius, informing him that the agreement with company X was being terminated since Landsbanki was in liquidation. The client was asked to sign a waiver and a transfer of funds. Attached was an invoice from Mossack Fonseca of $830 for the client to pay. When the client contacted the liquidator’s office in Luxembourg he was told he should not be in possession of these documents and they should either be returned or destroyed. Needless to say, the client kept the documents.

Company X is in the Offshoreleak database, shown as being owned by Landsbanki and four unnamed holders of bearer shares. – Widely used in offshore companies, bearer shares are a common way of hiding beneficial ownership. Though not a proof of money laundering, the Financial Action Task Force, FATF, considers bearer shares to be one of the characteristics of money laundering.

This shows that Landbanki Luxembourg set up a Panama company in the name of this client although the client did not sign any of the necessary documents needed to set it up. Also, that the liquidator’s office knew of this. (This account is based on the September 2009 email from Landsbanki Luxembourg to the client and a statement from the client).

Other clients I have heard from were offered offshore companies but refused. The story of company X only came out because of the information mistakenly sent from the liquidator to the client.

Landsbanki Luxembourg clients now wonder if companies were indeed set up in their names, if their funds were sent there and if so, what became of these funds. This has led them to attempt legal action in Luxembourg against the liquidator. Only the liquidator will know if it was a common practice in Landsbank Luxembourg to set up offshore companies without clients’ consent, if money were moved there and if so, what happened to these funds.

The curious role of a certain Philomène Ruberto

Invariably, the equity release loans in France and Spain were not sold directly by Landsbanki Luxembourg but through agents. This is another parallel to FX lending characterised by this pattern. According to the Austrian Central Bank this practice increases the FX borrowing risk as agents are paid for each loan and have no incentive to inform the client properly of the risks involved.

One of the agents operating in France was a French lady, Philomène Ruberto. In 2011, well after the collapse of Landsbanki, the Landsbanki Luxembourg was putting great pressure on the equity release borrowers to repay the loans. At this time, Ruberto contacted some of the clients in France. Claiming she was herself a victim of the bank, she offered to help the clients repay their loans by brokering a loan through her own offshore company linked to a Swiss bank, Falcon Private Bank, now one of several banks caught up in the Malaysian 1MDB fraud.

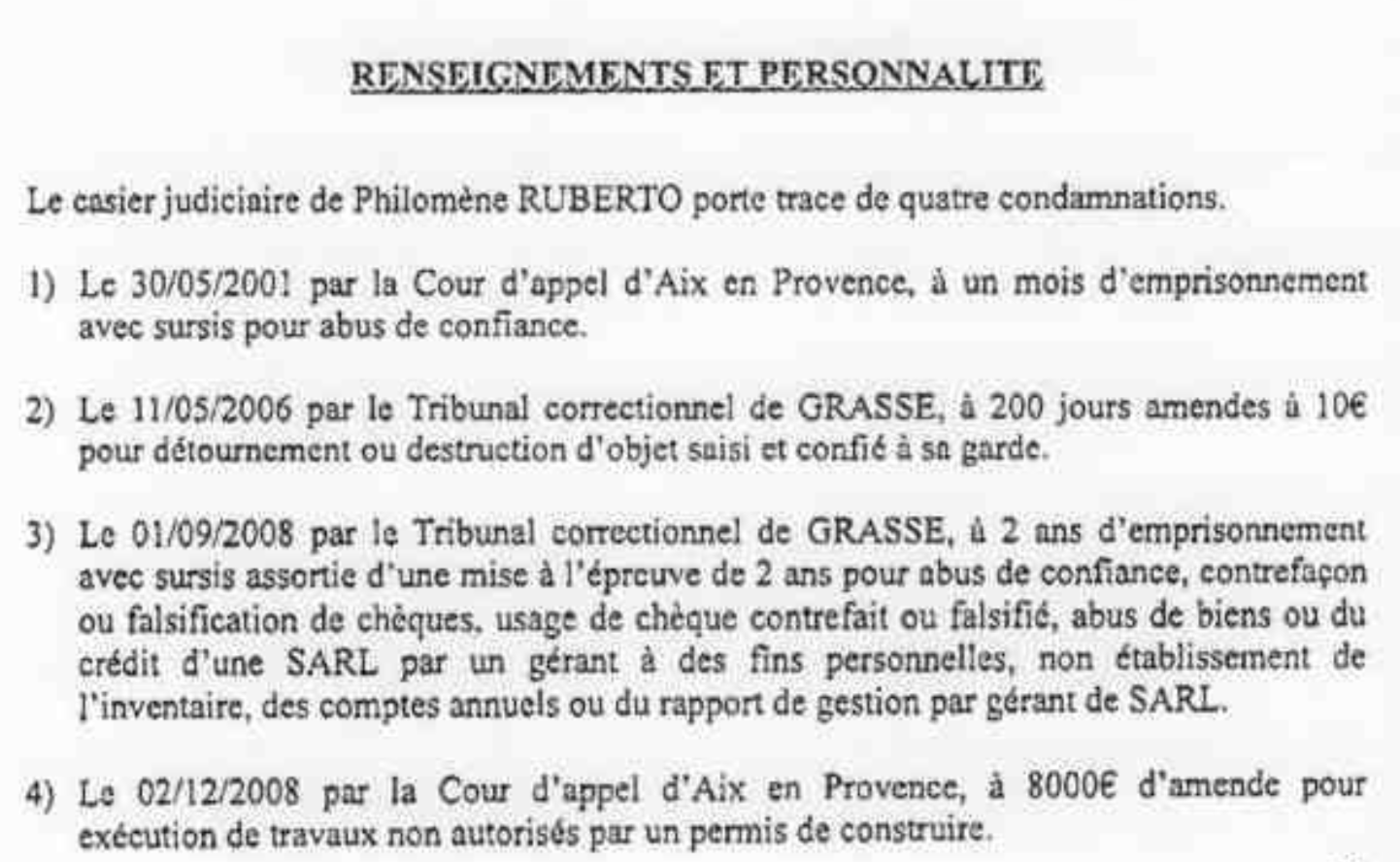

Some clients accepted the offer but that whole operation ended in court, where the clients accused Ruberto of fraud and breach of trust. In a civil case judgement at the Cour d’appel d’Aix en Provence in spring 2013, the judge listed a series of Ruberto’s earlier offenses, committed before and during the time she acted as an agent for Landsbanki:

This case was sent on a prosecutor. In a penal case in autumn 2014 Ruberto was sentenced by Tribunal Correctionnel de Grasse to 36 months imprisonment, a fine of €15,000 in addition to the around €190,000 she was ordered to pay the civil parties. According to the 2104 judgement Ruberto was, at the time of that case, detained for other causes, indicating that she has been a serial financial fraud offender since 2001.

But Ruberto’s relationship with Landsbanki Luxembourg prior to the bank’s collapse has a further intriguing dimension: GD Invest, a company owned by Ruberto and frequently figuring in documents related to her services, was indeed also one of Landsbanki Luxembourg largest borrowers. The SIC Report (p.196) lists Ruberto’s company, GD Invest, as one of the bank’s 20 largest borrowers, with a loan of €5,4m.

In 2007, at the time Ruberto was acting as an agent in France for Landsbanki Luxembourg, she not only borrowed considerably funds but, allegedly, on very favourable terms. In March 2007, GD Invest borrowed €2,7m and then further €2.3m in August 2007, in total almost €5,1m. Allegedly, Ruberto invested €3m in properties pledged to Landsbanki but the remaining €2m were a private loan. It is not clear what or if there was a collateral for that part.

By the end of 2011, Ruberto’s debt to Landsbanki Luxembourg was in total allegedly €7,5m. In January 2012 it is alleged that the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator made her an offer of repaying €2,4m of the total debt, around 1/3 of the total debt. Ruberto’s track record of fraudulent behaviour from 2001, raises questions to her ties first to Landsbanki and then to Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator. (The overview of Ruberto’s role is based on emails and court documents provided by Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers.)

Inconsistent information from the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidator

From 2012, when I first heard from Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release borrowers, inconsistent information from the liquidator has been a consistent complaint. The liquidator had then been, and still is, demanding repayment of sums the clients do not recognise. There are also examples of the liquidator coming up with different figures not only explained by interest rates. The borrowers have been unwilling to pay because there are too many inconsistencies and too many questions unanswered.

As mentioned above, Landsbanki Luxembourg was put in suspension of payment, in October 2008 and then into administration in December 2008. As far as is known, people who later took over the liquidation were called on to work at the bank during this time. During this time, many clients were informed that their properties had fallen in value, meaning that the collateral for their loan, the property, was inadequate. Consequently, they should come up with funds. At this time, there was no rational for a drop in property value. This is one of the issues the borrowers have, so far unsuccessfully, tried to raise with the liquidator.

Other complaints relate to how much had been drawn. One example is a client who had, by October 2008, in total drawn €200,000. This is the sum this client want to repay. Mid October 2008, after Landsbanki Luxembourg had failed, this client got a letter from a Landsbanki employee stating that close to €550,000, that the client had earlier wanted transferred to a French account, was still “safe” on the Landsbanki account. This amount was never transferred but the liquidator later claimed it had been invested and demanded that the client repay it.

The liquidator has taken an adversarial stance towards these clients. The clients complain of lack of transparency, inconsistent information, lack of information and lack of will to meet with them to explain controversies.

The role and duty of a liquidator

By late 2009 the liquidator had sold off the investments. This is what liquidators often do: after all, their role is to liquidate assets and pay creditors. However, a liquidator also has the duty to scrutinise activity. That is for example what liquidators of the banks in Iceland have done. A liquidator is not defending the failed company but the interests of creditors, in this case the sole creditor, LBI ehf.

Incidentally, the liquidator has not only been adversarial to the clients of Landsbanki but also to staff. In 2011 the European Court of Justice ruled against the liquidator in reference for a preliminary ruling from the Luxembourg Cour du cassation brought by five employees related to termination of contract.

Liquidators have great investigative powers. In addition to documents, they can also call in former staff as witnesses to clarify certain acts and deeds. If this had been done systematically the things outlined above would be easy to ascertain such as: is it proper in Luxembourg that a bank systematically invests clients’ funds in the bank’s own bonds? Was the investment strategy sound – or was there even a strategy? Were clients’ funds systematically moved offshore without their knowledge? If so, was that done only to generate fees for the bank or were there some ulterior motives? And have these funds been accounted for? A liquidator can take into account the circumstances of the lending and settle with clients accordingly.

And how about informing the State Prosecutor of Landsbanki’s investments on behalf of clients in Landsbanki bonds and the offshoring of clients without their knowledge?

But having liquidators in Luxembourg asking probing questions and conducting investigations is possibly not cherished by Luxembourg regulators and prosecutors, given that the country’s phenomenal wealth is partly based on exactly the kind of dirty deals seen in the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg.

LBI ehf – the only creditor to Landsbanki Luxembourg

Landsbanki Luxembourg has only one creditor – the LBI ehf, the estate of the old Landsbanki Iceland. According to the LBI 2017 Financial Statements the expected recovery of the Landsbanki Luxembourg amounts to €84,3m, compared to €74,3m estimated last year. The increase is following what LBI sees as a “favourable ruling by the Criminal Court in Paris on 28 August 2017,” i.e. that all those charged were acquitted.

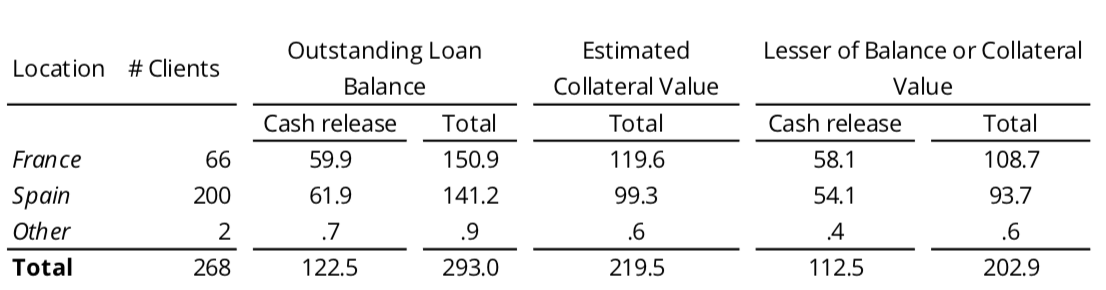

The only assets in Landsbanki Luxembourg are the equity release loans. The breakdown of the loans, in EUR millions, in the LBI 2017 Statements is the following:

Further to this the Statements explain that “LBI’s claims against the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate amounted to EUR 348.1 million, whereas the aggregate balance of outstanding equity release loans amounted to EUR 293.0 million with an estimated recoverable value … of EUR 84.3 million.”

As pointed out, the information “regarding legal matters pertaining to the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate is mainly based on communications from that estate‘s liquidator, and not all of such information has been independently verified by LBI management.”

Apart from the criminal action in Paris and the appeal of the August 2017 judgment, the Financial Statements mention other legal proceedings: “Landsbanki Luxembourg is also subject to criminal complaints and civil proceedings in Spain. … In November 2012, several customers in France and Spain brought a criminal complaint in Luxembourg against the liquidator, alleging that the former activities of Landsbanki Luxembourg are criminal and thus that the estate’s liquidator should be convicted for money laundering by trying to execute the mortgages. Other criminal complaints have been filed in Luxembourg in 2016 and 2017 based on the same grounds against the liquidator personally.”

This all means that “LBI’s presented estimated recovery numbers are subject to great uncertainty, both in timing and amount.”

What is Luxembourg doing?

It is not the first time I ask this question here on Icelog. In July 2013 there was the news from Luxembourg, according to the Luxembourg paper Wort, that there were two investigations on-going in Luxembourg related to Landsbanki. This surfaced in the Luxembourg parliament as the Justice Minister Octavie Modert responded to a parliamentary question from Serge Wilmes, from the centre right CSV, Luxembourg’s largest party since founded in 1944.

According to Modert both cases related to alleged criminal conduct in the Icelandic banks. One investigation was into financial products sold by Landsbanki. “…the deciding judge is making great strides,” she said, adding that in order not to jeopardize the investigation, the State Attorney was unable to provide further details on the results already achieved.”

Sadly, nothing further has been heard of this investigation.

In spring 2016 the Luxembourg financial regulator, Commission de surveillance du secteur financier, CSSF had set up a new office to protect the interests of depositors and investors. This might have been good news, given the tortuous path of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients to having their case heard in Luxembourg – CSSF has so far been utterly unwilling to consider their case.

The person chosen to be in charge is Karin Guillaume, the magistrate who ruled on the Landsbanki Luxembourg liquidation in December 2008. As pointed out in PaperJam, Guillaume has been under a barrage of criticism from the Landsbanki clients due to her handling of their case, which somewhat undermines the no doubt good intentions of the CSSF. From the perspective of the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients, CSSF has chosen a person with a proven track record of ignoring the interests of depositors and investors.

So far, Luxembourg authorities have resolutely avoided investigating Landsbanki and the other Icelandic banks. In Iceland almost 30 bankers, also from Landsbanki, and others close to the banks have been sentenced to prison, up to six years in some cases (changes to Icelandic law on imprisonment some years ago mean that those sentenced serve less than half of that time in prison before moving to half-way house and then home; they are however electronically tagged and can’t leave the country until the time of the sentence is over).

In the CSSF 2012 Annual Report its Director General Jean Guill wrote:

During the year under review, the CSSF focused heavily on the importance of the professionalism, integrity and transparency of the financial players. It urged banks and investment firms to sign the ICMA Charter of Quality on the private portfolio management, so that clients of these institutions as well as their managers and employees realise that a Luxembourg financial professional cannot participate in doubtful matters, on behalf of its clients.

Almost ten years after the collapse of Landsbanki, equity release clients of Landsbanki Luxembourg are still waiting for the promised investigation, wondering why the liquidator is so keen to soldier on for a bank that certainly did participate in doubtful matters.

*In court, the French singer Enrico Macias mentioned that all his documents were in English. I found this strange since I had seen documents in French from other clients and knew there was a French documentation available. When I asked Landsbanki Luxembourg clients this pattern emerged. All the clients asked for contracts in their own language. When the non-French clients asked for contracts in English they were told the documentation had to be in French as the contracts were operated in France. Conversely, the French were told that the language was English as it was an English scheme. I have now seen this consistent pattern on documents for the various clients. – Here is a link to all Icelog blogs, going back to 2012, related to the equity release loans. Here is a link to the Landsbanki Luxembourg victims’ website.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Landsbanki equity release borrowers lose at first instance court in Paris

After investigations by judge Renaud van Ruymbeke on Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans the case against its main shareholder and chairman of the board Björgólfur Guðmundsson and eight ex Landsbanki employees was concluded in a Paris court yesterday 28 August: the judge acquitted all of them. The group of borrowers who have been seeking answers and clarification to their situation is hoping the prosecutor will appeal.

The main issue addressed by Justice Olivier Geron in the magnificent Saint-Chapelle yesterday was alleged fraud by the nine accused bankers. After clarifying some procedural issues, the judge read for an hour his verdict with gusto, making only a short break when he realised that one page was missing from his exposé.

The Justice established that the financial collapse in Iceland had not affected the bank in Luxembourg and there had been no connection between events in Iceland and Luxembourg. – That is one view but we should of course keep in mind that the Landsbanki Luxembourg operations were closely connected to the financial health and safety of the mother bank in Iceland as funds flowed between these banks and the Landsbanki Luxembourg did indeed fail when the mother bank failed.

The Justice also considered if the behaviour of the individuals involved could be characterised as fraudulent behaviour and concluded that no, it could not. Thirdly, he considered the quality of the lending, if the clients had been promised or guaranteed the loans could not go wrong. He concluded there had been no guarantees and consequently, no fraud had been committed.

Things to consider

I have dealt with the Landsbanki Luxembourg at length on Icelog (see here) and would argue that the reasoning of the French Justice did not address the grounds on which suspicions were raised that then led to the French investigation.

France is not exactly under-banked: it raises questions why the loans against property in France (and Spain, another case) were all issued from a foreign bank in Luxembourg. Keep in mind that equity release loans, very common for example in the UK some twenty years ago, were all but outlawed there (can’t be issued against a home, i.e. a primary dwelling). This is not to say these loans should be banned but, like FX loans (another frequent topic on Icelog) they are not an everyman product but only of use under very special circumstances.

It is also interesting to keep in mind that other Nordic banks were selling equity release loans out of Luxembourg. Also there, problems arose and in many cases the banks have indeed settled with the clients, thus acknowledging that the loans were not appropriate. Consequently, the cost should be shared by the bank and its clients, not only shouldered by the clients.

The judge seemed taken up with the distinction between promises and guarantees, that the clients had perhaps been promised but not guaranteed that they could not lose, not lose their houses set as collaterals. – The witnesses were however very clear as to what exactly had been spelled out to them. Yes, borrowers bear responsibility to what they sign but banks also bear responsibility for what is offered.

One thing that came up during the hearing in May was the intriguing fact that English-speaking Landsbanki borrowers got loan documentation in English whereas a French borrower like the singer Enrico Macias got documents in English to sign. One English borrower told me he had asked for an English version, was told he would get one but it never arrived. So at least in this respect there was a concerted action on behalf of the bank to, let’s say, diminished clarity.

Landsbanki managers have been sentenced in Iceland for market manipulation. This is interesting since many of the borrowers realised later that contrary to their wish for low-risk investments their funds had been used to buy Landsbanki bonds, without their knowledge and consent.

And now to Luxembourg

As I have repeatedly pointed out, Luxembourg has done nothing so far to investigate banks operating in the Duchy. The concerted actions by the prosecutors in Iceland show that in spite of the complexity of modern banking banks can be investigated and prosecuted. All the dirty and dirtiest dealings of the Icelandic banks went through Luxembourg, also one of the key organising centres of offshorisation in the world.

In spite of the investigations and sentencing in Iceland, nothing has surfaced in Luxembourg in terms of investigating and prosecuting. One case regarding Kaupthing Luxembourg is under investigation there but so far, no charges have been brought.

A tale of two judges and their conflicting views

Judge Renaud van Ruymbeke is famous in France for taking on tough cases of white-collar and financial crimes. Justice Olivier Geron is equally famous for acquitting the accused in such cases. One of Geron’s latest is the Wildenstein case last January where a large tax scandal ended in acquittal, thanks to Geron.

After the Enron trial and the US there has been a diminished appetite there for bringing bankers and others from the top level of the business community to court, a story brilliantly told by Jess Eisinger in The Chickenshit Club – and nothing good coming since the Trump administration clearly is not interested in investigating and prosecuting this type of crimes.

In so many European countries it is clear that prosecuting banks is a no-go or no-success zone. As shown by Ruymbeke’s investigations there is the French will there but with a judge like Geron these investigations tend to fail in court.

Update: the Public Prosecutor in charge of the Landsbanki case has decided to appeal the 28 August decision, meaning the case will come up again in a Paris court.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Iceland: the most offshorised country in the world?