The Georgiou affair: how Greece keeps failing the political corruption test

After the election in Greece last summer, the country seemed to be on a positive path away from populism towards a more stable political environment. Though born into his party New Democracy, the new prime minister, Kyriakos Mistotakis, brought with him the air of the outside world: he had been a banker and consultant in London, before entering Greek politics in the early 2000s. Yet, he seems to stick to the same common thread as his predecessors in office since 2011: the persecution of the former head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, who took over as the head of the revamped Greek statistical office in August 2010 following the exposure in 2009 of how the national statistics had been falsified. Intriguingly, Georgiou and his staff have been persecuted relentlessly by political forces, whereas the falsification of the national statistics has not even been investigated at all. And not only that: those in positions of responsibility for the statistics from the time of falsified statistics sued Andreas Georgiou for slander and won at first instance civil court in 2017; since then, Georgiou’s hearing to appeal this decision has been continuously postponed, most recently to September 2020.

Just like Icelanders, Greeks earned a lot of sympathy when Greece tumbled into a financial crisis in 2009. But the Greek crisis exposed that the political ruling class in Greece had, since the end of the 1990s, falsified the Greek national statistics, i.e. the government deficit and debt were considerably higher than the published figures showed. For example, the deficit in 2006, 2007 and 2008 had been presented in official Greek statistics in mid-2009, just before the Greek crisis erupted, at 2.8%, 3.6% and 5% of GDP, respectively. However, the real figures, which were calculated by ELSTAT, the reformed statistical office, in 2010, were about double that, reaching 6.2%, 6.8% and 9.9% of GDP, respectively. And the government debt, which had been misreported at oscillating from 96 to 99% of GDP those years, was actually rising and had reached 110% of GDP by end 2008.

After years of legal wrangling, there seems to be no end in sight of the persecutions of the statistician who put Greek statistics on the path stipulated by European regulations on national statistics. Persecutions, which are an affront to Greek and European rule of law on many counts. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wants to confirm that the bad habits of falsified statistics are well and truly over and that Greece is firmly in the core of the European Union, it should give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou instead of punishing him for doing his job according to the European and Greek law.

Exposed: Greek statistical frauds… from 1997 to 2003

Greek statistics, as they are now for the years before the crisis hit, are not what Greek statistics were showing before autumn of 2009. Not for the first time, there was a lingering suspicion that not all was well with Greek statistics. Before joining the euro in 2001, the Greek budget deficit and public debt dived miraculously low, well below their less glorious average in the years before joining the euro. Although only the deficit figure ever went below the required Maastricht criteria, Greece was allowed to join the euro.

The lingering suspicion was there for a reason. Already in 2004 Eurostat had discovered that the debt and deficit dip around the euro entry was no miracle but manipulation: Greek authorities simply reported the wrong figures. In 2004, Eurostat’s Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures showed that this had been an on-going story from 1997 to 2003.

Consequently, the Greek statistical authorities, the then National Statistical Service of Greece, NSSG, was forced to revise its data upward for the years 1997 to 2003, including for the test year of 1999 for Greece’s entry into the Eurozone, above the criteria set by the EU for Greece: Revisions in statistics, and in particular in government deficit data, are not unusual… However, the recent revision of the Greek budgetary data is exceptional.” – The unusual aspect was that the wrong figures did not stem from missing or faulty data but from deliberate misreporting. The real figures were dismal so “better” figures, even though wrong, were reported.

Exposed again in 2009: repeated falsifications of national statistics

After the exposure in 2004, Greek statistics were under intense and unprecedented scrutiny. But NSSG was not prepared to abandon its earlier bad practices. In autumn 2009 the ECOFIN Council requested a new report, this time from the EU Commission, due to “renewed problems in the Greek fiscal statistics” after the “reliability of Greek government deficit and debt statistics (has) been the subject of continuous and unique attention for several years.”

Greek figures on debt and deficit had, yet again, significant problems: First, deficit forecasts for 2009 changed drastically between March 2009 and September 2009 and then the forecasts changed again even further in October 2009. Regarding the actual statistics, the EC report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics, published in January 2010, showed that the statistics for the actual 2008 deficit had been revised upward significantly (by 2.7 % of GDP). Again, as the report pointed out, such a revision was rare in EU member states “but have taken place for Greece on several occasions.” Once the real statistics for 2009 were available in April 2010, the numbers proved to be higher than any of the projections provided earlier and previous years’ statistics were again revised upwards.

As earlier, the faulty statistics had not been produced solely at the NSSG but were also made with components produced at the General Accounting Office (GAO) and other parts of the Ministry of Finance, as well as other public sector institutions responsible for providing data to NSSG. There was political interference and “deliberate misreporting” with the NSSG, GAO, MoF and other institutions involved in the reporting all playing their part, according to the January 2010 EC report. In total, the word “misreporting” was used eight times in the report.

Events before the setting up of ELSTAT and Georgiou’s time there

The Goldman Sachs, GS, off-market swap story was one chapter in the faulty statistics saga and one of many examples of misreporting affecting government deficit and debt statistics. In 2008, when Eurostat made official enquiries in all member states on off-market swaps, Greek authorities informed Eurostat promptly that the Greek state had engaged in nothing of the sort.

This statement turned out to be a blatant lie as Eurostat found out when investigating the matter in 2010; the findings were published in a Eurostat report (p.16) in November 2010. By 2009, this misreporting was understating the level of the Greek government debt by 2.3 percent of GDP. As with many other examples of faulty statistics, this misreporting, on the off-market swaps and the ensuing effect on government debt, was not a single event but a deceit running for years, in this case since 2001, where several Greek government agencies played their part.

Needless to say, fiddling with the numbers did not eradicate the actual debt and deficit problem. While this deceit was being uncovered in the last quarter of 2009 and early 2010, Greece was losing access to markets. Negotiations on a bailout were complicated by unreliable information on Greek public finances. On May 2, 2010, as the first Greek Memorandum of Understanding was signed, accompanied by a €110bn loan – €80bn from European institutions and €30bn from the IMF – it was clear that the crucial figures of debt and deficit might still go up.

Following these major failures at the NSSG, its head had resigned in mid-October 2009. With the new government of George Papandreou taking office in early October 2009, there were changes at the leadership of the MoF and the GAO, with a new minister, vice minister and general secretaries. However, the ranks below remained unchanged, as did the mentality.

With a new government and following these exposures the laws on official statistics were changed in the spring of 2010. NSSG was abolished, replaced by a new statistical office, ELSTAT. Andreas Georgiou, who having been with the IMF for more than 20 years, returned home to be the head of the new statistical office. After Georgiou took over, the last upward revisions to government deficit and debt data were done.

The context of the 2009 deficit and the statistical adjustments 2009 to 2010

It is important to keep in mind the context for the 2009 deficit: there was the forecasted deficit of 3.9% of GDP, put forth by the MoF and conveyed to the European Commission by NSSG in April 2009 and then the estimate of the actual 2009 deficit of 13.6%, as produced and reported by NSSG in April 2010. All of this, an upward adjustment of almost 10 percentage points of GDP, took place before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT in August 2010.

With the 2009 deficit number of 13.6% in April 2010, way up from the originally forecasted 3.9%, it was still clear and publicised by Eurostat that the final figure could be higher. As indeed it was: the final adjustment from 13.6% to 15.4% was made by Georgiou and his team. The actual monetary figure behind the last revision of the deficit figure was about 4 billion euro.

This final adjustment made by Georgiou and his team seemed at the time wholly innocuous and a straightforward continuation of the earlier and much larger adjustments. But things were changing in Greece, though not in the direction of what those hoping for new and better times in Greece, would have hoped for.

The worm pit of Greek politics

Greek politics was a veritable worm pit during these months of fears over the country’s finances as the Papandreou government negotiated rescue packages and bailouts – in May 2010 and in June 2011 – with the IMF and European institutions.

After the elections that New Democracy lost in early October 2009, Antonis Samaras replaced the long-standing and earlier so powerful leader of the party of 12 years, Kostas Karamanlis. Karamanlis had been prime minister from 2004 until he lost the elections in 2009, that is during the time of the second round of the fraudulent statistics. In a much-noted speech in September 2011, Samaras attacked George Papandreou, accusing him of manipulating the statistics after Papandreou came to power in 2009, claiming Papandreou had done this only to discredit Kostas Karamanlis. This speech proved fateful, not for Papandreou but for ELSTAT’s president Andreas Georgiou.

Shortly after the Samaras’ speech, Georgiou was called to the parliament to explain the revision of the deficit and debt figures he had done. He was accused of ignoring national interests and inflating the 2009 figures under instruction of Eurostat to push Greece into the Adjustment Programme, set up to save the Greek state.

This narrative ignored four facts: the main corrections had been done before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Georgiou followed the same European regulation on national accounts statistics (Regulation 2223/96) and the same European Statistics Code of Practice as all other statistical offices in the EU; Greece had entered the Adjustment Programme three months before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT; Greece had repeatedly reported faulty data up to 2004 and then again up to end of 2009.

Political figures both on the left and the right of the political spectrum united against the ELSTAT president as if the only reason for the country’s debt and deficit problems were the statistics. The Greek Association of Lawyers even accused Georgiou of high treason.

Politicians unite in finding a scapegoat for the crisis: ELSTAT staff

In addition to the parliamentary hearing, the Samaras’ speech sat another thing in motion: a prosecutor opened a case against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers and eventually pressed criminal charges in January 2013. In August 2013 an investigating judge recommended that the case be dropped as nothing was found to merit taking the case further.

However, political interventions, out in the open for all to see, kept the case alive in the Greek judicial system where it has been like a yo-yo: two additional times, in 2014 and 2015, prosecutors proposed that the case be dropped. However, what followed were interventions from nearly all sides of the political spectrum, fuelling the narrative of “false statements on the 2009 deficit and debt,” thus allegedly causing the Greek state to suffer staggering damages. A narrative that pushed the case to trial where the punishment should be relative to the damages, calculated to amount to €171bn, effectively amounting to a prison sentence for life.

In 2015 the charges against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers, for allegedly making false statements on the 2009 statistics, were dropped by the Appeals Court Council after proceedings behind closed doors. However, this decision was annulled by the Supreme Court in 2016 after a proposal by Greece’s Chief Prosecutor and the Appeals Court Council, with new members, had to reconsider the case.

In 2017, the Appeals Court Council decided again to drop the charges, but the Supreme Court yet again annulled the decision, following yet another proposal for annulment by the Chief Prosecutor, an extraordinary move in Greek legal history. Then, in March 2019, the Appeals Court Council, under yet a new composition, decided for a third time to drop the charges against Georgiou and two senior staff regarding the alleged inflation of the deficit. This time, the decision was not annulled by the Supreme Court.

An acquittal that did not end the case

However, charges against Georgiou for alleged violation of duty, for not bringing the 2009 revised deficit and debt figures to a vote by the former board of ELSTAT before their publication in November 2010, were upheld. This, despite proposals to the contrary, by various investigating judges and prosecutors assigned to the case on three different occasions, in 2013, 2014 and 2015. Eventually, Georgiou was tried in open court in 2016 and acquitted.

However, this acquittal did not put an end to the case: ten days later, and before even the rationale of the acquitting decision had been made available, another prosecutor annulled the acquittal and Georgiou had to be retried in a “Double Jeopardy” trial in 2017. He was convicted to two years in jail, a suspended sentence unless he gets another conviction within three years. Georgiou appealed to the Greek Supreme Court, but his appeal was rejected, and the conviction sustained in a 2018 Supreme Court decision.

In court, Georgiou had argued that he was following both Greek and EU law, which refer to the European Statistics Code of Practice, making it clear that the head of the statistical authority has the “sole responsibility for deciding on statistical methods, standards and procedures, and on the content and timing of statistical releases”.

Georgiou requested the Greek courts to put – as provided in the Treaties – a pre-trial question to the European Court of Justice on the matter of the interpretation of the European Statistics Code of Practice in this matter; the courts ignored Georgiou’s request. Instead the convicting decision chose to use a blatantly false translation and interpretation of the European Statistics Code of the Practice asserting that “sole responsibility for deciding” does not really mean what is stated in the Code.

It seems safe to conclude that the conviction of Andreas Georgiou to two years in jail for not putting up the revised deficit and debt statistics to a vote does not rhyme with Greek and European rule of law. If the Greek Government of Mitsotakis wanted to set Greece back on the right track in this fundamental area and show that Greece is firmly in the core of the EU, it should initiate a re-examination of the case and give the Greek courts an opportunity to right a wrong and to exonerate Andreas Georgiou as he did his job according to the European and Greek law.

Further, two criminal cases

There are also two other ongoing criminal cases in Greece involving Andreas Georgiou.

In September 2016, the Chief Prosecutor of Greece ordered a new, preliminary criminal investigation into allegedly the 2009 deficit figures. This case, not the same as the case in which Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff were acquitted in 2019, implicated not only Georgiou and the two ELSTAT staff for inflating the deficit figures but also officials from the European Commission, Eurostat and the IMF. So far, no charges have been pressed and Georgiou has not been summoned by the assigned prosecutor.

Another criminal case against Andreas Georgiou is with regard to his requesting ELSTAT staff in 2013 to sign a statistical confidentiality declaration, as required under the European Statistics Code of Practice, Indicator 5.2, for the purpose of protecting the private information of households and enterprises. There were two separate preliminary criminal investigations initiated in mid-2013 related to the Code, later combined into one. To this date no charges have been pressed but, as with the above-mentioned case, there is no evidence that the case has been closed.

If Greece and its political class wants to stop the scapegoating, all these cases against Andreas Georgiou ought to be dropped.

In addition to criminal cases: civil cases

In 2014, a civil case for criminal slander was brought against Georgiou. The plaintiff was Nikos Stroblos, who had been director of national accounts of the Greek statistics office in 2006 to 2010. Stroblos claimed Georgiou had engaged in criminal slander when he, as head of ELSTAT issued a press release in 2014, defending the final revised 2009 deficit and debt statistics produced by ELSTAT after Georgiou took over. The press release was published because of the legal proceedings since 2011 and the continuous attacks from most of the Greek political spectrum.

In 2017, the First Instance Civil Court decided that Georgiou had committed what is called in Greek legal terminology “simple slander,” meaning that what Georgiou said in his press release was true but had hurt the plaintiff’s reputation, (as opposed to “criminal slander”, whereby false statements are made to hurt somebody’s reputation). Thus, the court decided that Georgiou told the truth but he should not have made the statement he did. To atone for this, Georgiou was obliged to pay a compensation to the plaintiff and make a public apology in the Greek newspaper, Kathimerini, in the form of publishing large parts of the court decision against him.

When Georgiou appealed the decision, things took a peculiar turn: the appeal hearing has been postponed time and again. The last delay happened in January this year: the case was scheduled for January 16 but then postponed, for more than nine months, until September 24, 2020.

There is a peculiar irony here: Georgiou is appealing a court decision that found him guilty of “simple” slander for publicly defending his agency’s work; in layman’s terms, he was found liable for making true statements that happened to hurt someone’s reputation, an actual crime in Greece. If found liable, the person who restored the credibility of Greek statistics will have to publicly apologize to the person who was fudging the data previously and pay him compensation. This outcome would further damage Greece’s troubled image in the eyes of the global community.

European Convention on Human Rights: cases should be heard within a reasonable time

Now, six years after this civil case started, and nine years after Georgiou was first put under investigation, he and his family are still living with these never-ending court proceedings and the eternal postponements. It is of interest to keep in mind Article 6.1. of the European Convention on Human Rights: In the determination of his civil rights and obligations or of any criminal charge against him, everyone is entitled to a fair and public hearing within a reasonable time by an independent and impartial tribunal established by law.

Interestingly, one of Stroblos’ witnesses in the civil suit against Georgiou is Nikos Logothetis, who was vice-chairman of the board of ELSTAT when the board had demanded to vote on the revised 2009 deficit and debt figures in November 2010. Only weeks earlier, Logothetis was forced to resign from the ELSTAT board after the Greek police found that Logothetis had hacked Georgiou’s private email. A criminal investigation was opened against Logothetis at that time and in early 2011 two charges, of felony and misdemeanour, were pressed against him.

However, both cases against him were dropped for reasons that are difficult to fathom in the context of the rule of law and how Georgiou’s cases have fared in the Greek courts: one case was dropped as the court did not consider it before the five-year statute of limitations expired; the other case was thrown out because a receipt for a €20 fee, due when a complaint is filed, could not be found in the court file. And then, as if this was not scandalous enough, the court later met Logothetis’ request: that his computer, which the police had previously confiscated and which still contained Georgiou’s stolen emails, should be handed back to him.

International support for Georgiou – but that does not save him from the persecutions

There have been many instances of international support for Andreas Georgiou over the years. Below are some examples of recent ones.

The European Commission has repeatedly mentioned Georgiou’s case in its periodic reports of the post-program reviews for Greece. In its November 2019 Enhanced Surveillance Report it noted: The Commission has continued to monitor developments in relation to the legal proceedings against … the former President and senior staff of the Hellenic Statistical Authority. The case against the former Hellenic Statistical Authority President A. Georgiou related to charges filed in connection with fiscal statistics has been irrevocably dismissed. An appeal introduced by Mr. Georgiou in a civil defamation lawsuit is scheduled to be heard in January 2020.”

The International Statistical Institute noted in a statement published in December 2019: “It is of great concern to us that the legal harassment of Mr Georgiou is not yet over. There are three legal cases against him in Greece which are still open. He took these actions in accordance with statistical principles in his capacity as head of the national statistics office… Defending official statistics, as required by the UN Fundamental Principles of Statistics and the European Statistics Code of Practice, should not lead to any legal proceedings and even less to damages being awarded and public apologies. Now is the time for a fresh start in Greek statistics, and the ending of the victimisation of Mr Georgiou.”

The Board of the American Statistical Association also issued a statement in December 2019 stating inter alia that the Association was “troubled by Greece’s continued persecution of its former head statistician. Now in the ninth year, there are still open investigations and trials of Georgiou, a government professional who is loyal to his country. Greece’s new government provides an opportunity to remedy the unjust official treatment of Georgiou. Ending the prosecutions, accusations and legal proceedings and exonerating Georgiou would signal Greece’s commitment to accurate and ethical official statistics. This, in turn, could help foster foreign investment and overall confidence among Greece’s international partners, which helps Greece’s economy.”

Political witch hunt

In August 2017, Nikos Konstandaras columnist at Kathimerini and the New York Times warned that the Georgiou affair was “a witch hunt, not a thirst for justice.” Konstandaras concluded:

Beyond the injustice and the terrible personal cost for a fellow citizen, beyond the damage to the country’s credibility, the most tragic aspect of the affair is that people who know how dangerous this all is are investing in fantasies and encouraging fanaticism.

History, though, will record the role they played. In the end they will be loaded with more blame than that which they are trying to saddle onto others.

Now, more than two and a half years after this was written, the persecution of a civil servant who did what he was supposed to do, is still ongoing. Much to the shame of Greece the man who led ELSTAT from August 2010 to August 2015, putting in procedures for correct reporting of statistics following the exposure of fraudulent statistics for over a decade, is being prosecuted. At the same time, the people who for years provided false and fraudulent statistics to Greece, European authorities and the world, enjoy total impunity and even participate and benefit from Georgiou’s prosecutions.

In an article in the Washington Post as recently as 2 January this year, Georgiou’s case was brought up, pointing out how both professional rivals and politicians had decided to scapegoat Georgiou during the contagious time he was in office, creating the narrative that “he had “inflated” the deficit to “trap” Greece into accepting bigger international bailouts, with harsher conditions, than it needed.”

As pointed out, “the Greek government has changed hands multiple times” since the legal cases against Georgiou started, a particularly damning point for Mitsotakis and his government. “So far, though, those in power have continued to foment or tolerate the scapegoating of civil servants, and refused to help Georgiou clear his name.”

A worrying disincentive to service truthful information

The numerous prosecutions are utterly damning for the Greek political system. Equally, that the IMF and EU have not been able to adequately and decisively assist the quest for truthful statistics. It is a travesty of the rule of law that a civil servant has for more than eight years been persecuted for doing his job truthfully, to the professional standards expected of his office. A travesty that is harmful for not only for Greek civil servants and their work but elsewhere. Or, as concluded in the Washington Post article 2 January:

“And make no mistake: Georgiou may be the primary victim of this weaponization of the judicial system, but he is hardly its only target. Other civil servants — in Greece and in other countries weighing their commitment to rule of law — are watching and learning what happens when a number cruncher decides to tell the truth.”

In December 2016, Georgiou said to Icelog: “The numerous prosecutions and investigations against me and others that have been going on for years – as well as the persistence of political attacks and the absence of support by consecutive governments – have created disincentives for official statisticians in Greece to produce credible statistics. As a result, we cannot rule out the prospect that the problem with Greece’s European statistics will re-emerge. The damage already caused concerns not only official statistics in Greece, but more widely in the EU and around the world, and will take time and effort to reverse.”

How can Greece, the political class in Greece, face the fact that an innocent man is persecuted, and the real fraud of national statistics has never been investigated?

*Icelog has followed the Georgiou case since I visited Greece in 2015. See here for earlier blogs on the case.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

The Luxembourg walls that seem to shelter financial fraud

People, mostly pensioners, who previously took out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, have for a decade been demanding that Luxembourg authorities look into alleged irregularities, first with the bank’s administration of the loans, then how the liquidator dealt with their loans after Landsbanki failed. The Duchy’s regulator, CSSF, has staunchly refused to consider this case. Yet, following criminal investigations in Iceland into the Icelandic banks, where around thirty people have been found guilty and imprisoned over the years, no investigation has been opened in Luxembourg into the Duchy operations of the Icelandic banks so far. Criminal investigation in France against the Landsbanki chairman at the time and some employees ended in January this year: all were acquitted. Recently, investors in a failed Luxembourg investment fund claimed the CSSF’s only interest is defending the Duchy’s status as a financial centre.

Out of many worrying aspects of the rule of law in Luxembourg that the Landsbanki Luxembourg case has exposed, the most outrageous one is still the intervention in 2012 of the State Prosecutor of Luxembourg, Robert Biever. At the time, a group of the bank’s clients, who had taken out equity release loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, were taking action against the bank’s liquidator Yvette Hamilius. Then, out of the blue, Biever, who neither at the time nor later, had investigated the case, issued a press release. Siding with Hamilius, Biever stated that a small group of the Landsbanki clients, trying to avoid paying back their loans, were resisting to settle with the bank.

Criminal proceedings in Iceland against managers and shareholders of the Icelandic banks, where around 30 people have been found guilty, show that many of the dirty deals were carried out in Luxembourg. Since prosecutors in Iceland have obtained documents in Luxembourg in these cases, all of this is well known to Luxembourg authorities. Yet, neither the regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, nor other authorities have apparently seen any ground for investigations, with one exception. A case related to Kaupthing has been investigated but, so far, nothing has come out of that investigation (here more on that case, an interesting saga in itself).

However, it now seems that not only the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have their doubts about on whose side the CSSF really is. Investors in a Luxembourg-registered fund claim they were defrauded but that the CSSF has been wholly unwilling to investigate their claims. Their conclusion: the CSSF’s only mission is to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre, which undermines “its responsibility to protect investors.”

That would certainly chime with the experience of the Landsbanki clients. Further, the fact that Luxembourg is a very small country, which greatly relies on its financial sector, might also explain why the Landsbanki Luxembourg clients have found it so difficult even to find lawyers in Luxembourg, willing to take on their case.

A slow realisation – information did not add up

It took a while before borrowers of equity release loans from Landsbanki Luxembourg started to suspect something was amiss. The messages from the bank in the first months after the liquidators took over, in October 2008, were that there was nothing to worry about. However, it quickly materialised that there was indeed a lot to worry about: the investments, which had been made as part of the loans, seemed to have been wiped out; what was left was the loan, which had to be paid off.

In addition, there were conflicting information as to the status of the loans, the amounts that had been paid out and the status on the borrowers’ bank accounts. The borrowers, mostly elderly pensioners in France and Spain, many of them foreigners, took out loans with Landsbanki Luxembourg, with their properties in these two countries as collaterals. To begin with, they were to begin with dealing with this situation alone, trying to figure out on their own what was going on. It took the borrowers some years until they had found each other and had founded an action group, Landsbanki Victims Action Group.

Landsbanki clients in Spain are part of an action group in Spain against equity release loans, The Equity Release Victims Association, Erva. The Landsbanki clients have taken the Landsbanki estate to court in Spain in order to annul the administrator’s recovery actions there. Lately, the clients have been winning but given that cases can be appealed it might take a while to bring these cases to a closure. The administrator’s attempt to repatriate Spanish court cases against the bank to Luxembourg have, so far, apparently not been successful.

Criminal case in France, civil cases in France and Spain

Finding a lawyer, both for the group and the single individuals who took action on their own, proved very difficult: it has taken a lot of time and effort and been an ongoing problem.

By January 2012, a French judge, Renaud van Ruymbeke, had opened an investigation into the loans in France. The French prosecutor lost the case in the Criminal Court of First Instance in Paris in August 2017; on 31 January 2020, the Paris Appeal Court upheld the earlier ruling, acquitting Landsbanki Luxembourg S.A., in liquidation and some of its managers and employees at the time. The case regarded the operations before the bank’s collapse, the administrator was not prosecuted. The Public Prosecutor as well as the borrowers, in a parallel civil case, have now challenged the Paris Appeal Court decision with a submission to the Cour de cassation.

While this case is still ongoing, the administrator’s recovery actions in France were understood to be on hold. According to Icelog sources, that has not entirely been the case.

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity before its demise in October 2008

The main issues with the bank’s marketing and administration of the loans has earlier been dealt with in detail on Icelog but here is a short overview:

As Hamilius mentioned in an interview in May 2012 with the Luxembourg newspaper Paperjam, the loans were sold through agents in Spain and France. After all, the whole operation of the equity release loans depended on agents; Landsbanki Luxembourg was operating in Luxembourg, not in France and Spain.

The use of agents has an interesting parallel in how foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been sold in Europe (see Icelog on FX loans and agents). In the case of FX loans, the Austrian Central Bank deemed that one reason for the unhealthy spread of these risky loans was exactly because they were sold through agents. Agents had great incentives to sell the loans and that the loans were as high as possible but no incentive to warn the clients against the risk. Interestingly, the sale of financial products through agents has been found illegal in some European cases regarding FX loans.*

Other questions relate to how the equity release loans were marketed, i.e. the information given, that the bank classified the borrowers as professional investors, which greatly diminished the bank’s responsibility in informing the clients and also what sort of investments they would choose for the investment part of the loan. Life insurance was a frequent part of the package, another familiar feature in FX loans.

Again, given rulings by the European Court of Justice on FX loans, it seems incomprehensible that the same conditions should not apply to equity release loans as FX loans. After all, there are exactly the same issues at stake, i.e. how the loans were sold, how borrowers were informed and classified (as professional investors though they clearly were not).

How appropriate the investments were for these types of loans and clients is an other pertinent question in this saga. After the collapse of Landsbanki Luxembourg, the borrowers discovered to their great surprise that in some cases the investments were in Landsbanki bonds, even in its shares, as well as in shares and bonds of the two other Icelandic banks, Glitnir and Kaupthing.

That the bank would invest its own loans in the bank’s bonds is simply outrageous. Already in analysis of the Icelandic banks made by foreign banks as early as 2005 and 2006, the high interconnection of the Icelandic banks, was seen as a risk. Thus, if the CSSF had at all had its eyes on these investments, made by a bank operating in Luxembourg, the regulator should have intervened.

It was also equally wholly unfitting to buy bonds in the other Icelandic banks: their credit default swap, CDS, spread made their bonds far from suitable for low-risk investments. – Interestingly, the administrator confirmed in the Paperjam interview 2012 that the loans were indeed invested in short-term bonds of Landsbanki and the two other banks: thus, there is no doubt that this was the case. – Only this fact per se, should have made the liquidator take a closer look at the time.

The value of the properties used as collaterals also raises questions. The sense is that the bank wanted to lend as much as possible to each and every borrower, thus putting a maximum value of the properties put up as collateral.

One of many intriguing facts regarding the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans exposed in the French criminal case was when French borrowers told of getting loan documents in English and English borrowers of getting documents in French. As pointed out earlier on Icelog this seems to indicate a concerted effort by the bank to diminish clarity (at least in some cases, clients were promised they would get the documents in their language of choice, i.e. English borrowers getting documents in English, but the documents never materialised).

Again, this raises serious questions for the CSSF: did the bank adhere to MiFID rules at the time? And did the liquidator really see nothing worth reporting to the CSSF?

Landsbanki Luxembourg: opacity after its demise in October 2008

After Landsbanki Luxembourg failed in October 2008, Yvette Hamilius and Franz Prost were appointed liquidators for Landsbanki. Following Prost’s resignation in May 2009, Hamilius has been alone in charge. As the Court had originally appointed two liquidators the Court could have been expected to appoint another one after Prost resigned. That however was not the case. Not in Luxembourg. There have been some rumours as to why Prost resigned but nothing has been confirmed.

Be that as it may, the relationship between Hamilius and the borrowers has been a total misery for the borrowers. One of the things that early on led to frustration and later distrust were conflicting and/or unexplained figures in statements. Clarification, both on figures on accounts, and more importantly regarding the investments, was not forthcoming according to borrowers Icelog has heard from.

Hamilius’ opinion of the borrowers could be seen from the Paperjam interview in 2012 and from the remarkable statement from State Prosecutor Biever: the liquidator’s unflinching view was that the borrowers were simply trying to make use of the fact the bank had failed in order to save themselves from repaying the loans.

The interview and the statement from Biever came as a response to when a group of borrowers tried to take legal action against the Landsbanki Luxembourg and its liquidator. In the interview, Hamilius was asked if she was solely trying to serve the interest of Luxembourg as a financial centre, something she staunchly denied.

The action against Landsbanki Luxembourg has so far been unsuccessful, partly because Luxembourg lawyers are noticeably unwilling to take action against a bank, even a failed bank. In that sense, anyone trying to take action against a Luxembourg financial firm finds himself in a double whammy: the CSSF has proved to be wholly unsympathetic to any such claims and finding a lawyer may prove next to impossible.

Why was the investment part of the Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans killed off?

The key characteristic of equity release loans is that this product consists of a loan and investment, two inseparable parts. However, that proved not to be the case in the Landsbanki Luxembourg loans. Suddenly, after the demise of the bank, the borrowers found themselves to be debtors only, with the investment wiped out. This did fundamentally alter the situation for the borrowers.

The liquidator seems allegedly to have taken the stance that to a great extent, there was nothing to do about the investments in these cases where the bank had invested in Icelandic bank shares and bonds. That is an intriguing point: as pointed out earlier, the bank should never have been allowed to make these investments on behalf of these clients.

In Britain, as in many European countries, the law in general stipulates that if a lender fails, loans are not to be payable right away. As far as I can see, this counts for equity release loans as well: both parts of the loan should be kept going, the loan as well as the investment. Frequently, a liquidator sells off the package at a discount, for another company to administer, in order to be able to close the books of the failed bank.

This has not been the case in Landsbanki Luxembourg equity release loans, the investments were wiped out – and yet, Luxembourg authorities have paid no attention at all to the borrowers’ claims of unfair treatment by the liquidator.

As mentioned above, Hamilius’ version of the sorry saga is that the borrowers are simply unwilling to repay the loan.

The dirty deals of the Icelandic banks in Luxembourg

The recurrent theme in so many of the criminal cases in Iceland after the banking collapse 2008 against bankers and others related to the banks is the role of the banks’ subsidiaries in Luxembourg. The dirtiest parts of the deals were done through the Luxembourg subsidiaries (particularly noticeable in the Kaupthing cases). Since Hamilius has assisted investigations into Landsbanki in Iceland, she will be perfectly well aware of the Icelandic cases related to Landsbanki.

The administrators of the Icelandic banks in Iceland were crucial in providing material for the criminal proceedings in Iceland. Yet, as far as can be seen, the administrator has allegedly not deemed it necessary to take a critical look at the Landsbanki operations in Luxembourg. Which is why no questions regarding the equity release loans have been raised by the administrator with Luxembourg authorities.

The incredibly long winding-up saga at Landsbanki Luxembourg

One interesting angle of the winding-up of Landsbanki Luxembourg saga is the time it is taking. The administrators (winding-up boards) of the three large Icelandic banks, several magnitudes larger than Landsbanki Luxembourg, more or less finished their job in 2015, after which creditors took over the administration of the assets, mostly to sell them off for the creditors to recover their funds. The winding-up proceedings of LBI ehf., the estate of Landsbanki Iceland, came to an end in December 2015, when a composition agreement between LBI ehf. and its creditor became effective.

For some years now, the LBI ehf has been the only creditor of Landsbanki Luxembourg, i.e. all funds recovered by the liquidator go to LBI ehf. Formally, LBI ehf has no authority over the Landsbanki Luxembourg estate. Yet, it is more than an awkward situation since LBI ehf is kept in the waiting position, while the liquidator continues her actions against the equity release borrowers, whose funds are the only funds yet to be recovered.

That said, Luxembourg is not unused to long winding-up sagas. The fall of the Luxembourg-registered Bank of Credit and Commerce International, BCCI, in 1991, was one of the most spectacular bankruptcies in the financial sector at the time, stretching over many countries and exposing massive money laundering and financial fraud. Famously, the winding-up took well over two decades, depending on countries. Interestingly, Yvette Hamilius was one of several administrators, in charge of the process from 2003 to 2011; the winding-up was brought to an end in 2013.

The CSSF on a mission to protect its financial sector, not investors

Recently, another case has come up in Luxembourg that throws doubt on whose interest the CSSF mostly cares for: the financial sector it should be regulating or investors and deposit holders. A pertinent question, as pointed out in an article in the Financial Times recently (23 Feb., 2020), since Luxembourg is the largest fund centre in Europe, with €4.7tn of assets under management and gaining by the day as UK fund managers shift business from Brexiting Britain to the Duchy.

The recent case seems to rotate around three investment funds – Columna Commodities, Aventor and Blackstar Commodities – domiciled in Luxembourg, sub funds of Equity Power Fund. As early as 2016, the CSSF had expressed concern about the quality of the investments: astoundingly, 4/5 of the investments were concentrated in companies related to a single group. Lo and behold, this all came crashing down in 2017.

The investors smelled rat and contacted David Mapley at Intel Suisse, a financial investigator who specialises in asset recovery. Mapley has a success to show: in 2010 he won millions of dollars from Goldman Sachs on behalf of hedge funds, which felt cheated by the bank.

In order to gain insight into the Luxembourg operations, Mapley was appointed a director of LFP I, one of the investment funds in the Equity Power Fund galaxy. (Further on this story, see Intel Suisse press release August 2018 and coverage by Expert Investor in January and October 2019.)

According to the FT, the directors of LFP I claim the CSSF has not lived up to its obligation under EU law. They have now submitted a complaint against the CSSF to European Securities and Markets Authority, Esma, which sets standards and supervises financial regulators in the EU.

In a letter to Esma, Mapley states that the CSSF’s “marketing mission to promote Luxembourg as a financial centre” has undermined its focus on protecting investors. Mapley also alleges the CSSF has attempted to quash the directors’ investigations into mismanagement and fraud by the funds’ previous managers and service providers in order to undermine the funds’ efforts “and prevent any reputational risk”. – That is, the reputational risk of Luxembourg as a financial centre.

As FT points out, investors in a Luxembourg-listed fund that invested in Bernard Madoff’s $50bn Ponzi scheme have also accused the CSSF of leniency, i.e. sheltering the fraudster and not the investors.

Luxembourg, the stain on the EU that EU is unwilling to rub off

Worryingly, the CSSF’s lenient attitude might be more prominent now than ever as Luxembourg competes with other small European jurisdictions of equally doubtful reputation such as Cyprus and Malta (where corrupt politicians set about to murder a journalist, Daphne Caruana Galizia, investigating financial fraud; brilliant Tortoise podcast on the murder inquiry) in attracting funds leaving the Brexiting UK. Esma has been given tougher intervention powers, though sadly watered down from the original intension, in order to hinder a race to the bottom. It is very worrying that the EU does not seem to be keeping an eye on this development.

As long as this is the case, corrupt money enters Europe easily, with the damaging effect on competition, businesses, politics – and ultimately on democracy.

*Foreign currency loans, FX loans, have been covered extensively on Icelog, see here. For a European Court of Justice decision in the first FX loans case, see Árpád Kásler and Hajnalka Káslerné Rábai v OTP Jelzálogbank Zrt, Case C‑26/13.

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Jim Ratcliffe and his feudal hold of Icelandic salmon rivers and farming communities

The largest landowner in Iceland owns around 1% of Iceland, mostly land adjacent to salmon rivers in the North East of Iceland – and he is not Icelandic but one of the wealthiest Brits, James or Jim Ratcliffe, a Sir since last year, of Ineos fame. His secretive acquisitions of farms with angling rights have been facilitated by the Icelandic businessmen who for years have been investing in salmon rivers through offshore companies. Opaque ownership is nothing new. Though the novelty is the grip on these rivers now held by a foreigner, with no ties to the community and assets valued at just above the Icelandic GDP, the central problem is mainly the nationality of the owner, but the concentration of ownership.

“If you are doing honest business, I assume you would feel better if you could talk freely about it. This secrecy breeds suspicion,” says Ævar Rafn Marinósson, a farmer at Tungusel in North East Iceland. The secretive business he is talking about is the business of buying farms adjacent to salmon rivers in his part of Iceland.

The secrecy is not new: for more than a decade, the ownership of the attractive salmon rivers in Iceland has been hidden in an opaque web of on- and offshore companies. That opacity might now hit the community when rivers and land is increasingly being held by one man, Jim Ratcliffe, whose assets are estimated £18.15bn. Through direct and indirect ownership, Ratcliffe owns over forty Icelandic farms concentrated in and around Vopnafjörður, which gives him the control of angling rights in some of the best salmon rivers in Iceland.

The petrochemical giant Ineos is Ratcliffe’s source of wealth. Interestingly, his salmon investments are part of his recent, rapidly growing investment in sport, from cycling, sailing and football to his, so far, tentative interest in British Premier League football clubs with price tags of billions. Ratcliffe claims that his petrochemical industries are run in an environmentally friendly way and strongly denies that his sport investments are any form of green-washing.

The secrecy surrounding Ratcliffe’s Icelandic investments, so out of proportions in this rural community of salmon and sheep farmers, has bred both rumours and suspicion that splits apart families, neighbours and the local communities as they debate whether the funds on offer are a substitute for losing control of the angling and the land.

Also, because Ratcliffe is a distant owner. He leaves it to his Icelandic representatives to talk to the farmers some of whom, like Marinósson, refuse to sell and as a consequence feel harassed. And then there are the pertinent questions of how Ratcliffe’s funds flow into the local economy, as one farmer opposed to Ratcliffe’s growing hold of the region, mentioned in an interview in the Icelandic media.

Following Ratcliffe’s purchases, foreign ownership of land is now a hot topic in Iceland. The government is looking at legal restrictions to limit foreign ownership. A new poll shows that 83.6% of Icelanders support this step. – But that might be a mistaken angle: the problem is not foreign ownership but concentrated ownership.

“I’m not upset with Ratcliffe, he’s just a businessman pursuing his interests. I’m upset with the government of Iceland that is letting this happen,” says Marinósson. He is not the only one to point out that a new legislation might come too late for the salmon rivers in the North East.

Angling – strictly regulated

Though far from being a mass industry, angling has long been both a beloved sport in Iceland and attracted wealthy foreigners. In the early and mid 20th century, English aristocrats came to fish in Iceland. In the 1970s and 1980s, the Prince of Wales was fishing in Hofsá, now controlled by Ratcliffe. With the changing pattern of wealth came high-flyers from the international business world.

As angling interest grew, net fishing for salmon was restricted so as to let the angling flourish. In 2011, 90% of the salmon caught in Iceland was from angling. The annual average salmon catch is around 36.000 salmon, with the figures jumping over 80.000 in the best years. There are in total 62 salmon rivers with 354 rods allowed; the rivers in the North East are thirty, with 124 rods (2011 brochure in English; Directorate of Fisheries).

According to the Salmon and Trout Act from 2006, the fishing rights are privately owned by those who own the land adjacent to rivers and lakes. The fishing rights come with a string of obligations, supervised by the Directorate of Fisheries and most importantly: the fishing rights cannot be split from the land – the only way to control the angling is to own a farm or farms holding the angling right.

The owners of the farms owning a river or lake are obliged to set up a fishing association to manage the angling; both the necessary investment and the profit has to be shared according to the amount of land owned. The ownership is split according to voting rights and percentage owned.

Wielding control over the angling, these associations can decide either to manage the angling themselves or lease out the rights to angling clubs or other consortia.

From overfishing to highly regulated angling regime

Already in the 1970s, the fishing associations run by the farmers owning the best salmon rivers were increasingly leasing out the angling rights to groups of wealthy Icelandic anglers, mostly business men from Reykjavík.

In some rare cases, foreign anglers who frequented Iceland, held the angling rights through a lease. One attractive salmon river in the North East, Hafralónsá, where Ævar Rafn Marinósson and his family are among the owners, was leased by a Swiss angler from 1983 to 1994; from 1995 to 2003, a British and a French angler leased the river.

During the 1990s, the popularity of angling led to overfishing in many salmon rivers with tension between biology and the financial profits from the angling rights. But the owners of the angling rights quickly came to understand that overfishing would kill the goose laying the golden eggs, or rather the salmon that brought wealth to the community.

The angling is now restricted in many ways: each river has only a certain number of rods; the angling time is restricted to certain hours of the day and a certain amount of annual angling days, often 90 days, from mid-June.

In addition, some form of “fish and release” is in place in most if not all the highly sought after and expensive salmon rivers. All these protective measures have been driven by those who control the angling, i.e. the fishing associations owned by the landowners.

Foreign anglers mainly pursue the sporty fly-fishing, whereas Icelanders tend not to frown upon using spoons and worms. Icelandic anglers know it is good to fish with spoons and worms after the foreign fly-anglers have been “beating the river” as we say in Icelandic. That normally ensures great catch, a trick the Icelandic anglers are happy to use.

Angling – from farmers to wealthy business men

The leases related to the salmon rivers normally run for some years. The fees to the fishing associations are a significant part of income for the farmers. The lessees are normally obliged to undertake investment in the infrastructure around the river.

Part of cultivating the salmon population in the rivers is expanding the habitat. This is for example done by building “salmon-ladders,” enabling the salmon to migrate beyond waterfalls or other hindrances, potentially increasing the rods allowed in each river and thus making the river more profitable.

Those who rent the rivers try to sell each rod at as high a price as the market can tolerate. Angling in the best rivers in Iceland is an expensive sport, also because the fishing is sold as a package with accommodation and meals included.

No longer primitive huts, the best fishing lodges are like boutique hotels, where the best chefs in Iceland come and cook for discerning anglers with the wines to match. Part of the summer news in the Icelandic media is reporting on the number of salmon caught in the well-known rivers, size and weight, what tools were used and sometimes also who is angling where.

This is the angling of the very wealthy. But angling is also popular with thousands of ordinary Icelanders. Angling for salmon, trout and sea trout in less famous rivers and lakes, is an affordable and ubiquitous sport in Iceland.

The opaque ownership web that Ratcliffe is buying into

Incidentally, this development of buying farms, not just licensing the angling rights, has been going on in Iceland for decades. In the early 1970s, a medical doctor and keen angler in Reykjavík, Oddur Ólafsson, bought five farms along Selá. Decades and several owners later these farms are now owned by Ratcliffe.

Orri Vigfússon (1942-2017) was a businessman and passionate angler, who in 1990 set up the North Atlantic Salmon Fund as an international initiative in order to protect and support the wild North Atlantic salmon. Vigfússon was influential in Icelandic angling circles and well known in angling circles all around the North Atlantic. He was also primus motor in Strengur, a company that for decades has controlled the best rivers in the North East, now controlled by Ratcliffe.

The web of on- and offshore companies related to angling has been in the making in Iceland since the late 1990s, when the general offshorisation of wealthy Icelanders boomed through the foreign operations of the Icelandic banks. A key person in this web is an Icelandic businessman.

Born in 1949, Jóhannes Kristinsson has been living in Luxembourg for years. Media-shy in Iceland he was in business with flashy businessmen like the duo Pálmi Haraldsson and Jón Ásgeir Jóhannesson of Baugur fame, synonymous with the Icelandic boom before the 2008. Kristinsson seems to be linked to around 25 Icelandic companies.

By 2006, it was attracting media attention in Iceland that wealthy anglers were no longer just licencing the angling rights but were outright buying farms holding angling rights. One name figured more often than others, Jóhannes Kristinsson. In an interview at the time, Kristinsson said he probably owned only one farm outright but was mostly a co-owner with others, without wanting to divulge how much he owned.

The farmers felt they knew Kristinsson, a frequent guest in the North East and the opaque ownership did not seem much of an issue. However, the effect of the opacity is now becoming very clear as Kristinsson is selling to a foreigner with no ties to the community, leaving the community potentially little or no control over some of its glorious rivers and land.

Luxembourg, Ginns and Reid

Kristinsson’s ownership of lands and rivers in the North East seems to have been held in Luxembourg from early on. Dylan Holding is a Luxembourg company, registered in 2000, by BVI companies, which Kaupthing owned and used to offshorise its clients. No beneficial owner is named in any of the publicly available Dylan Holding documents but the company was set up with Icelandic króna, indicating its Icelandic ownership.

According to Dylan Holding’s 2018 annual accounts, the company, still filing accounts in Icelandic króna, held assets worth ISK2.6bn. Its 2017 accounts list eleven Icelandic holding companies, fully or majority-owned by Dylan Holding, among them Grænaþing. Last year, Ratcliffe bought Grænaþing, as part of the deal with Kristinsson; an indication of Kristinsson being the beneficial owner of Dylan Holding.

The names of two of Ratcliffe’s trusted Ineos lieutenant, Jonathan F Ginns and William Reid, are closely linked to Ratcliffe’s Icelandic ventures as to so many other Ratcliffe ventures. According to UK Companies House, Ginns sits or has been on the board of over seventy Ineos/Ratcliffe related companies, Reid on seven.

Ginns and Reid sit on the boards of three Icelandic companies previously owned by Dylan Holding indicating that these companies are now under Ratcliffe’s control. Whether Ratcliffe has bought Dylan Holding outright or where exactly his ownership stands at, remains to be seen but it seems safe to conclude that Ratcliffe now owns significantly more land on his own rather than, as earlier, through joint venture with Kristinsson and others. Kristinsson seems to be withdrawing, leaving Ratcliffe as the sole owner.

Ratcliffe’s rapid rise to being Iceland’s largest landowner

Jim Ratcliffe, the angler with the funds to indulge his salmon passion was nr.3 on the Sunday Times Rich List this year, with assets valued at £18.15bn, down from £20.05bn in 2018, when he ranked nr.1. A Brexiteer who is not waiting for Brexit to happen: after relocating to the UK from Switzerland, where Ratcliffe and Ineos were domiciled from 2010 until some months after the EU referendum in 2016, Ratcliffe moved to Monaco last year. Tax and regulation seem to be his main concerns.

Ratcliffe had been fishing in Vopnafjörður for some years without attracting any attention. It was not until late 2016, when he visibly started buying into the Icelandic angling consortia, that his name first appeared in the Icelandic media. By then, he already owned eleven farms in the area, both through sole ownership and through his share in Strengur. Local sources believe Ratcliffe started investing earlier in angling assets, hidden in opaque ownership structures.

In December 2016 it was announced that Ratcliffe had bought the major part of the single largest farmland in Iceland, Grímsstaðir. This mostly barren wasteland of glorious beauty in the highlands beyond Mývatn had been owned by Grímstaðir farmers and their families for generations. The Icelandic state was a minority owner and has retained its share of the land. Ratcliffe stated at the time he was buying Grímsstaðir because it was part of the Selá water system; buying the land was part of his plan to support and protect the wild salmon.

The Grímsstaðir deal drew a lot of media attention in Iceland because in 2011, a Chinese businessman and poet, Huang Nubo, had tried to purchase this land with unclear intentions. Nubo had some Icelandic friends from his university years but practically no assets abroad except some real estate in the US, which he seemed to struggle to maintain. In 2014, the Icelandic government vetoed Nubo’s plans: he was not European, and his plans lacked clarity.

For decades, Strengur, under changing ownership, has managed the angling rights in Selá and Hofsá, two of the best salmon rivers in the North East and bought up farms adjacent to the rivers. In 2012, a new 960sq.m fishing lodge opened by Selá, a good example of the investment done in order to improve the angling experience and cater to wealthy anglers.

Following a 2018 transaction Ratcliffe owns almost 87% of Strengur, a jump from the 34% he had owned earlier, meaning that he controls the angling rights in both Selá and Hofsá. Ratcliffe bought the 52.75% by purchasing a company owned by Jóhannes Kristinsson. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson (who features in this Ineos PR video) is now seen as Ratcliffe’s mouthpiece. He has ties to around twenty Icelandc companies, many of which are linked to Kristinsson.

The Ratcliffe Kristinsson consortium now owns 40 to 50 farms. But Ratcliffe is looking for more: earlier this year, Ratcliffe added one farm to his Icelandic portfolio. He now seems trying to secure ownership of yet another river, Hafralónsá.

The Icelandic media had reported that he had now secured majority in the angling association of that river but that does not seem to be the case. Ævar Rafn Marinósson is one of the owners of Hafralónssá. He says to Icelog that as far as he knows, Ratcliffe is still a minority owner.

The suspicion among those who are not in Ratcliffe’s fold is rife as a change in ownership might bring about drastic changes. With majority hold, Ratcliffe might for example drive the farmers in minority to bankruptcy by forcing through investments in the Hafralónsá angling association, which would wipe out the profits that make an important part of the farmers’ annual income.

Ratcliffe’s representative made Marinósson an offer to buy his farm. His answer was that the farm, which he owns with his parents, was not for sale. The representative then visited his elderly parents with the same offer, although it had been made clear to him that the farm was not for sale.

Misinformed passion

In a PR video from Ineos, Jim Ratcliffe talks of “overfishing and ignorance” that threat the salmon populations in Iceland. In the video Ratcliffe’s passion for salmon fishing is given as his drive for investing “heavily in the region to help expand the salmon’s natural breeding grounds” through constructing of salmon ladders in six rivers. The latter part of the video is about his investment in safari parks in Africa, with both initiatives presented as rising from Ratcliffe’s environmental concerns.

As mentioned earlier, the times of overfishing in Icelandic salmon rivers are long over. To portray Ratcliffe as a saviour of the salmon rivers in the North East is at best misinformed, at worst profoundly patronising to the farmers who have lived and bred salmon all their live and whose livelihoods have partly depended on the silvery fish. But the fact that Ratcliffe has the funds to follow his passion cannot be disputed.

In August this year Ineos Technology Director Peter S. Williams signed an agreement on behalf of Ratcliffe with the Marine and Fresh Water Institute in Iceland, where Ratcliffe takes on to fund salmon research to the amount of ISK80m, around £525.000. At the time it was announced that any profit from Strengur will be ploughed into maintaining and supporting the salmon populations in the rivers that Strengur controls. Strengur’s director Gísli Ásgeirsson said at the time that the aim was sustainability in cooperation with the farmers and local councils. There will be those in the local community who feel that cooperation is exactly what is lacking.

In a Rúv tv interview I did with Ratcliffe in 2017 (unfortunately no longer available online), Ratcliffe said he was driven by his passion for angling and the uniqueness of the unspoiled nature in Iceland, a value in itself. There is some speculation in Iceland that Ratcliffe’s angling investments might be driven by something else then his passion for angling.

Some think water as commodity in a world facing water shortage is his real interest, which would explain his emphasis on buying the rivers outright instead of joint venture or just renting the angling rights. Others, that plans by Bremenport to build a port in nearby Finnafjörður in order to service the coming Transpolar Sea Route might be in Ineos’ interest. Again, total speculation but heard in Iceland. – Ineos is investing in facilities in Willhelmshaven, where Bremenport is building a new container terminal.

Mushrooming sport investment: from millions in salmon and safari to, possibly, billions in Premier League football

Ratcliffe’s UK holding company for his Icelandic assets is Halicilla Ltd, incorporated in 2015, its business being “mixed farming.” Halicilla’s 2017 accounts list two Icelandic companies as assets, Fálkaþing, incorporated in 2013 and Grenisalir, incorporated in 2016, “Icelandic companies, which in turn hold land and fishing rights.”

Ratcliffe has been unwilling to divulge how much he has invested in Iceland but that can be gleaned with some certainty from the Halicilla accounts: its assets amounted to £9.7m in 2016, which with further acquisitions in 2017, had grown to £15.3m by the end of 2017, financed directly by the shareholder, i.e. Ratcliffe.

In addition to investments in Icelandic salmon rivers, Ratcliffe’s sports investments have mushroomed in the recent years. In December 2017, he announced his investment in luxury eco-tourism project in safari parks in Tanzania through a UK company, Falkar Ltd, incorporated in 2015. As Halicilla, Falkar is financed by Ratcliffe, with a loan of £6.3m, at the end of 2017. With his interest in sailing, Ratcliffe owns two yachts, one of them, Hampshire II a superyacht worth $150m, with two of his Ineos partners owning three yacths. In addition, Ratcliffe owns four jets, three Gulfstream jets and one Dassault Falcon.

Ratcliffe’s other sport investments involve much higher figures than his investments in salmon and safari. Last year, he invested £110m in Britain’s America’s Cup team. His investment in March in the cycling Team Sky, now Team Ineos, seemed to imply that the Team’s earlier budget of £34m would increase significantly. In 2017 he bought the Lausanne-Sport football club, where his brother is now the club’s president, and has recently completed a £88.7m deal to buy Ligue 1 club Nice.

The figures might rise: last year, Ratcliffe led an unsuccessful bid of £2bn for Chelsea FC and has aired his interest to buy his favourite team, Manchester United – one day, some super-star footballers might be practicing fly-fishing under Ratcliffe’s instructions in Vopnafjörður.

Split families and farming communities, threats and bullying

The farmers in the North East face a dilemma. It is in the interest of farmers to be able to sell their farm for a reasonable price if they intend to retire or give up farming for other reasons. However, seeing whole fjords and entire rivers now owned not by a consortium of wealthy anglers in Reykjavík but by a single foreigner, wholly unrelated to the country and the North East, with a strangle hold on the community, has spread unease.

When the Icelandic consortia started buying farms in order to gain control of the angling, the farmers often continued to live on the farm, as tenants. On the whole, the farms have continued to be farmed, though there are exceptions.

Ratcliffe has stated he is keen for the farmers to keep living on the farms and has offered them to stay as tenants. With money in the bank the tenants can profit from the land as earlier but no longer benefit from the angling rights as earlier or have any say on the use of the river.

Ratcliffe’s acquisitions have completely changed the game around the rivers. The novelty is his immense buying power. His entrance into the angling circles has split families and communities. To sell or not to sell is a burning question for many since Ratcliffe’s representatives keep making lucrative offers to the few farmers who have so far been unwilling to sell.

This is, as such, not entirely Ratcliffe’s fault – he simply has an exorbitant amount of money to indulge in one of his hobbies though he has shown little interest in learning from the farmers who know the rivers like the back of their hands. But this sowing of anger and unease has been the side effect of his investments. Perhaps also to some degree because of the people he has chosen to work with in Iceland; how well informed Ratcliffe is of the circumstances surrounding his investments is unclear.

Ratcliffe flies in and out of Iceland. The Icelanders who work for him are there and some live in the communities Ratcliffe has already bought or is trying to buy. His salmon shopping spree may be backed by the best intensions, but the side effect is effectively making him the ruler of a few hundred Icelanders who live off the land they love dearly. The land, which Ratcliffe visits at his leisure, once in a while.

Restrictions on ownership of land may come too late for the North East

Foreign ownership is a hot topic in Iceland for the time being, given the quick and enormous concentration of Ratcliffe’s ownership in the North East. But it would be wrong to focus on foreign ownership – the real problem is concentrated ownership.

Ratcliffe is not the only foreign landowner in Iceland. There are a few others but there is increased interest from abroad for land in Iceland. One foreign owner closed off his land with signs of “Private road,” much to the irritation of his Icelandic neighbours since free passage in the country side is seen as a general right in Iceland. One practical reason is the gathering of sheep: sheep roam freely in summer and farmers need to roam just as freely when the sheep is gathered in autumn.

Though rapidly developing, luxury tourism is still a rarity in Iceland, and has so far not led to land being closed off. As Ratcliffe’s Tanzania investment shows, he is interested in luxury tourism. Seeing angling turning into an even more rarefied luxury than it already is, marketed mainly for people in Ratcliffe’s wealth bracket, is not an enticing thought for most Icelanders.

The government led by Katrín Jakobsdóttir, leader of the Left Green party (Vinstri Grænir), with the Independence party (Sjálfstæðisflokkur) and the Progressives (Framsóknarflokkur), is now under pressure to consider means to limit foreign ownership. A working group has been gathering material and new law is promised this coming winter. One step in the right direction of focusing on concentrated ownership, not just foreign ownership, would be to reintroduce pre-emptive purchase rights of local councils, abolished in 2004.

Finding the proper criteria that drive rural development in the right direction will not be easy. But Icelanders are certainly waiting for that to happen – having stratospherically wealthy people, Icelandic or foreign, owning entire rivers and fjords on a scale not seen since the time of the feudal lords of the Icelandic sagas is not seen as positive rural development. When law is finally passed, it might be too late to prevent that to happen in the North East.

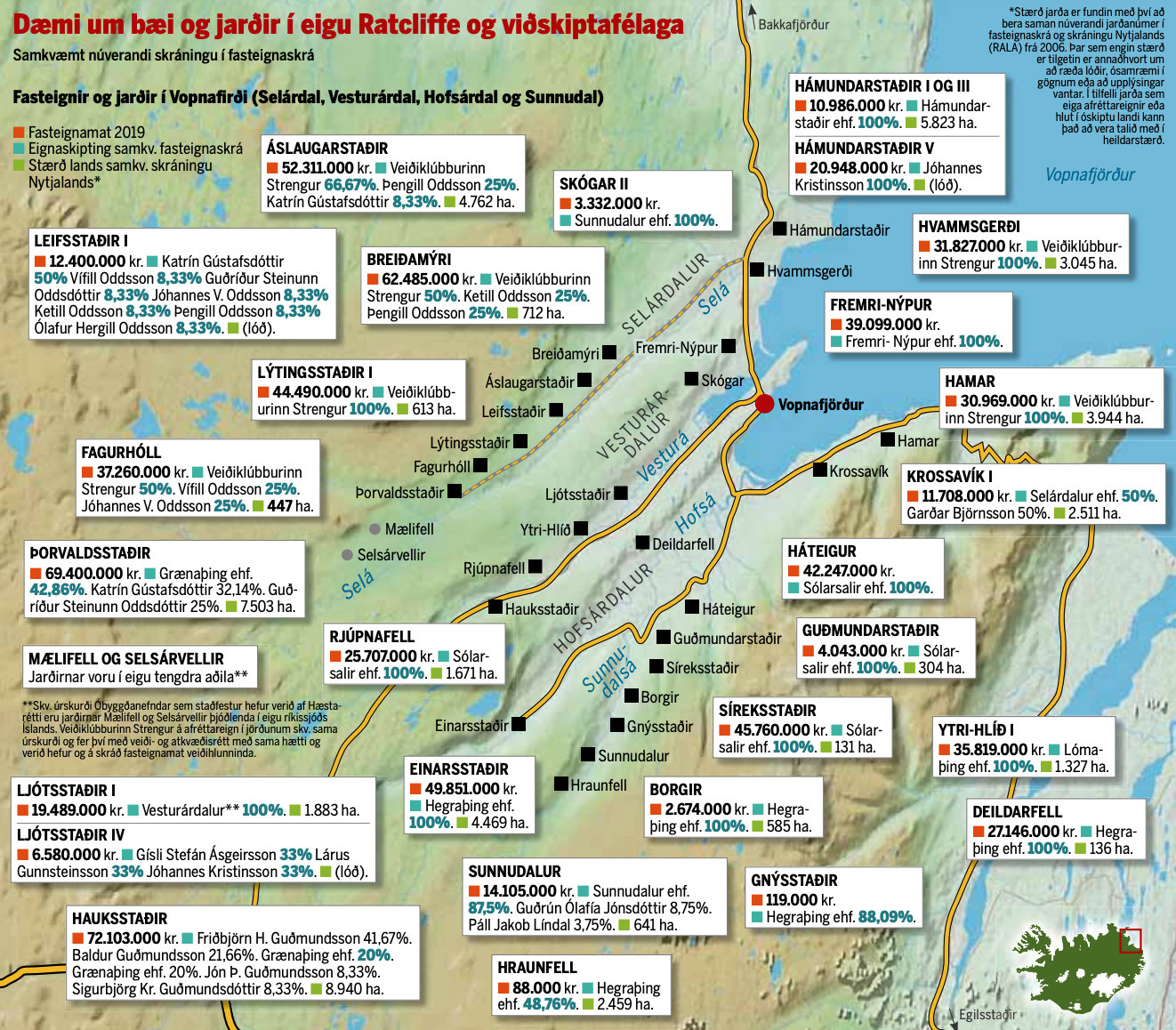

*This image is from a July 21 July 2018 article on Ratcliffe’s acquisitions in the Icelandic daily Morgunblaðið and shows ownerships of farms in Vopnafjörður (there are other farms in the neighbouring communities.)

Follow me on Twitter for running updates.

Kaupthing Luxembourg and Banque Havilland – risk, fraud and favoured clients

Banque Havilland has just celebrated its tenth anniversary: it is now ten years since David Rowland bought Kaupthing Luxembourg out of bankruptcy. A failed bank not only tainted by bankruptcy but severely compromised by stark warnings from the regulator, CSSF. Yet, neither the regulator nor the administrators nor later the new owner saw any reason but to keep the Kaupthing Luxembourg manager and key staff. In four criminal cases in Iceland involving Kaupthing the dirty deals were done in the bank’s Luxembourg subsidiary with back-dated documents. Two still-ongoing court cases, which Havilland is pursuing with fervour in Luxembourg, indicate threads between Kaupthing Luxembourg and Havilland, all under the nose of the CSSF.

“The journey started with a clear mission to restructure an existing bank and the ambition of the new shareholder to lay strong foundations, which an international private bank could be built on,” wrote Juho Hiltunen CEO of Banque Havilland on the occasion of Havilland’s 10th anniversary in June this year.

This cryptic description of the origin of Banque Havilland hides the fact that the ‘existing bank’ David Rowland bought was the subsidiary of Kaupthing Luxembourg, granted suspension of payment 9 October 2008, the same day that the mother-company, Kaupthing hf, defaulted in Iceland.

The last year of Kaupthing Luxembourg’s operations had been troubled by serious concerns at the Luxembourg regulator, Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier, CSSF, regarding the bank’s risk management and the management’s willingness to move risk from clients onto the bank.

Unperturbed by all of this, Rowland not only bought the bank but kept the key employees, including the bank’s Icelandic director, Magnús Guðmundsson, instrumental in selling Kaupthing Luxembourg to Rowland. Guðmundsson stayed in his job until 2010, when news broke in Iceland he was under investigation, later charged and found guilty in two criminal cases (two are still ongoing) in Iceland, where he has served several prison sentences. He was replaced by Jean-Francois Willems, another Kaupthing Luxembourg manager, CEO of Banque Havilland Group since 2017. Willems was followed by Peter Lang, also an earlier Kaupthing manager. Lang left that position when Banque Havilland was fined by the CSSF for breaches in money laundering procedures.

David Rowland’s reputation in his country of origin, Britain, was far from pristine – in Parliament, he has been called a ‘shady financier.’ However, all that seemed forgotten in 2010 when the media-shy tycoon was set to become treasurer of the Conservative Party, having donated in total £2.8m to the party in less than a year. As the British media revised on Rowland stories, Rowland realised he was too busy to take on the job and stepped out of the spotlight again.

In the Duchy of Luxembourg, Rowland was seen as fit and proper to own a bank. And the bank, CSSF had severely criticised, was seen as fit and proper to receive a state aid in the form of a loan of €320m in order to give the bank a second life.

Criminal investigations in Iceland showed that Kaupthing hf’s dirty deals were consistently carried out in Luxembourg. There were clearly plenty of skeletons in the Kaupthing Luxembourg that Rowland bought. Two still-ongoing legal cases connect Kaupthing and Havilland in an intriguing way.

In December 2018, the CSSF announced that Banque Havilland had been fined €4m and now had “restrictions on part of the international network” for lack of compliance regarding money laundering and terrorist financing, the regulator’s second heftiest fine of this sort. Eight days later the bank announced a new and stronger management team: a new CEO, Lars Rejding from HSBC. It was also said that there were five new members on the independent board but their names were not mentioned. An example of the bank’s rather sparse information policy.

KAUPTHING LUXEMBOURG: RISK, FRAUD AND FAVOURED CLIENTS

2007: CSSF spots serious lack of attention to risk in Kaupthing Luxembourg

On August 25 2008, the CSSF wrote to the Kaupthing Luxembourg management, following up on earlier exchanges. The letter shows that as early as in the summer of 2007, the CSSF was aware of the serious lack of attention to risk. The regulator’s next step, in late April 2008, was to ask for the bank’s credit report, based on the Q1 results, from the bank’s external auditor, KPMG. In the August 2008 letter, the CSSF identified six key issues where Kaupthing Luxembourg was at fault:

1 The CSSF deemed it unacceptable that Kaupthing Luxembourg financed the buying of Kaupthing shares “as this may represent an artificial creation of capital at group level.”

2 Analysing the bank’s loan portfolio, the CSSF concluded that the bank’s activity was more akin to investment banking than private banking as the bulk of credits were “indeed covered by highly concentrated portfolios (for example: (Robert) Tchenguiz, (Kevin) Stanford, (Jón Ásgeir) Johannesson, Grettir (holding company owned by Björgólfur Guðmundsson, Landsbanki’s largest shareholder, together whith his son, Björgólfur Thor Björgólfsson) etc.)” The CSSF saw this “as highly risky and we ask you to reduce it.” This could only continue in exceptional cases where the loans would have a clear maturity (as opposed to bullet loans that were rolled on).